Your cart is currently empty!

A History of Western Art Music

Chapter Five: The Early Baroque

Baroque music refers to the period or dominant style of Western classical music composed from about 1600 to 1750. The Baroque period is divided into three major phases: early, middle, and late. Overlapping in time, they are conventionally dated from 1580 to 1650, from 1630 to 1700, and from 1680 to 1750. Baroque music forms a major portion of the “classical music” canon, and is widely studied, performed, and listened to. The term “baroque” comes from the Portuguese word barroco, meaning “misshapen pearl”. The works of George Frideric Handel and Johann Sebastian Bach are considered the pinnacle of the Baroque period.

The Baroque saw the creation of common-practice tonality, an approach to writing music in which a song or piece is written in a particular key; this type of harmony has continued to be used extensively in Western classical and popular music. During the Baroque era, professional musicians were expected to be accomplished improvisers of both solo melodic lines and accompaniment parts. Baroque concerts were typically accompanied by a basso continuo group (comprising chord-playing instrumentalists such as harpsichordists and lute players improvising chords from a figured bass part) while a group of bass instruments—viol, cello, double bass—played the bassline. A characteristic Baroque form was the dance suite. While the pieces in a dance suite were inspired by actual dance music, dance suites were designed purely for listening, not for accompanying dancers.

During the period composers experimented with finding a fuller sound for each instrumental part (thus creating the orchestra), made changes in musical notation (the development of figured bass as a quick way to notate the chord progression of a song or piece), and developed new instrumental playing techniques. Baroque music expanded the size, range, and complexity of instrumental performance, and also established the mixed vocal/instrumental forms of opera, cantata and oratorio and the instrumental forms of the solo concerto and sonata as musical genres. Dense, complex polyphonic music, in which multiple independent melody lines were performed simultaneously (a popular example of this is the fugue), was an important part of many Baroque choral and instrumental works. Overall, Baroque music was a tool for expression and communication.

The Florentine Camerata

In the years centering on 1600 in Europe, several distinct shifts emerged in ways of thinking about the purposes, writing and performance of music. Partly these changes were revolutionary, deliberately instigated by a group of intellectuals in Florence known as the Florentine Camerata, and partly they were evolutionary, in that precursors of the new Baroque style can be found far back in the Renaissance, and the changes merely built on extant forms and practices. The transitions emanated from the cultural centers of Northern Italy, then spread to Rome, France, Germany, and Spain, and lastly reached England.

The Florentine Camerata, also known as the Camerata de’ Bardi, were a group of humanists, musicians, poets and intellectuals in late Renaissance Florence who gathered under the patronage of Count Giovanni de’ Bardi to discuss and guide trends in the arts, especially music and drama. They met at the house of Giovanni de’ Bardi, and their gatherings had the reputation of having all the most famous men of Florence as frequent guests After first meeting in 1573, the activity of the Camerata reached its height between 1577 and 1582.

Prior to the Camerata’s inception, there existed a popular sentiment among the Camerata’s Renaissance contemporaries that music should mimic the ancient roots of the Greeks. The current day’s thought held that the Greeks used a style between speech and song, and this belief guided the Camerata’s discourse. They were influenced by Girolamo Mei, the foremost scholar of ancient Greece at the time, who held—among other things—that ancient Greek drama was predominantly sung rather than spoken. Foundational for this belief was the writing of the Greek thinker Aristoxenus, who proposed that speech should set the pattern for song.

Largely concerned with a revival of the Greek dramatic style, the Camerata’s musical experiments led to the development of the stile recitativo. Cavalieri was the first to employ the new recitative style, trying his creative hand at a few pastoral scenes. The style later became primarily linked with the development of opera.

The criticism of contemporary music by the Camerata centered on the overuse of polyphony at the expense of the sung text’s intelligibility. Excessive counterpoint offended the ears of the Camerata because it muddled the affetto (“affection”) of the important visceral reaction in poetry. It is the job of the composer to communicate the affetto into an audible, comprehensible sound. Intrigued by ancient descriptions of the emotional and moral effect of ancient Greek tragedy and comedy, which they presumed to be sung as a single line to a simple instrumental accompaniment, the Camerata proposed creating a new kind of music. Instead of trying to make the clearest polyphony they could, the Camerata voiced an opinion recorded by a contemporary Florentine, “means must be found in the attempt to bring music closer to that of classical times.”

The musical style which developed from these early experiments was called monody. In the 1590s, it developed into a vehicle capable of extended dramatic expression through the work of composers such as Jacopo Peri, working in conjunction with poet Ottavio Rinuccini. In 1598, Peri and Rinuccini produced Dafne, an entire drama sung in monodic style: this was the first creation of a new form called “opera”. Though Peri’s Dafne was the first performed opera, its music has been lost to the centuries. Instead, Euridice, his second opera is most-often heralded as the history-making work. The new form of opera also borrowed, especially for the librettos, from an existing pastoral poetic form called intermedio; it was mainly the musical style that was new. The instrumentation for an opera from the Camerata composers (Caccini and Peri) was written for a handful of gambas, lutes, and harpsichord or organ for continuo.

Other composers quickly began to incorporate the ideas of the Camerata into their music, and by the first decade of the seventeenth century the new “music drama” was being widely composed, performed and disseminated. Instead of an immediate decline in contrapuntal vocal music, there was a time of coexistence and then an eventual synthesis of monody and polyphony. Florence, Rome, and Venice became the Italian capitals of innovation and synthesis.

Transition from Renaissance to Baroque in Instrumental Music

One key distinction between Renaissance and Baroque instrumental music is in instrumentation; that is, the ways in which instruments are used or not used in a particular work. Closely tied to this concept is the idea of idiomatic writing, for if composers are unaware of or indifferent to the idiomatic capabilities of different instruments, then they will have little reason to specify which instruments they desire.

According to David Schulenberg, Renaissance composers did not, as a general rule, specify which instruments were to play which part; in any given piece, “each part [was] playable on any instrument whose range encompassed that of the part.”Nor were they necessarily concerned with individual instrumental sonorities or even aware of idiomatic instrumental capabilities. The concept of writing a quartet specifically for sackbuts or a sextet for racketts, for instance, was apparently a foreign one to Renaissance composers. Thus, one might deduce that little instrumental music per se was written in the Renaissance, with the chief repertoire of instruments consisting of borrowed vocal music.

Howard Brown, while acknowledging the importance of vocal transcriptions in Renaissance instrumental repertoire, has identified six categories of specifically instrumental music in the sixteenth century:

- vocal music played on instruments

- settings of preexisting melodies, such as plainchant or popular songs

- variation sets

- ricercars, fantasias, and canzonas

- preludes, preambles, and toccatas

- music for solo voice and lute

While the first three could easily be performed vocally, the last three are clearly instrumental in nature, suggesting that even in the sixteenth century, composers were writing with specifically instrumental capabilities in mind, as opposed to vocal. In contention of composers’ supposed indifference to instrumental timbres, Brown has also pointed out that as early as 1533, Pierre Attaignant was already marking some vocal arrangements as more suitable for certain groups of like instruments than for others. Furthermore, Count Giovanni de’ Bardi, host of the Florentine Camerata, was demonstrably aware of the timbral effects of different instruments and regarded different instruments as being suited to expressing particular moods.

In the absence of idiomatic writing in the sixteenth century, characteristic instrumental effects may have been improvised in performance. On the other hand, idiomatic writing may have stemmed from virtuosic improvised ornamentation on a vocal line – to the point that such playing became more idiomatic of the instrument than of the voice.

In the early Baroque, these melodic embellishments that had been improvised in the Renaissance began to be incorporated into compositions as standardized melodic gestures. With the Baroque’s emphasis on a soloist as virtuoso, the range of pitches and characteristic techniques formerly found only in virtuosic improvisation, as well as the first dynamic markings, were now written as the expected standard. On the other hand, some of the instrumental genres listed above, such as the prelude and toccata were improvisation-based to begin with. Even in the early sixteenth century, these genres were truly, idiomatically instrumental; they could not be adapted for voices because they were not composed in a consistent polyphonic style.

Thus, idiomatic instrumental effects were present in Renaissance performance, if not in writing. By the early Baroque, however, they had clearly found their way into writing when composers began specifying desired instrumentation, notably Claudio Monteverdi in his opera scores.

Another crucial distinction between Renaissance and Baroque writing is its texture: the shift from contrapuntal polyphony, in which all voices are theoretically equal, to monody and treble-bass polarity, along with the development of basso continuo. In this new style of writing, solo melody and bass line accompaniment were now the important lines, with the inner voices filling in harmonies.

The application of this principle to instrumental writing was partly an extension of the forces of change in vocal writing stemming from the Florentine Camerata. The principle of a single, clear melody dominating a simple accompaniment easily carries over to the instrumental realm. This is seen in the proliferation of hitherto unknown solo instrumental sonatas beginning shortly after Caccini’s Le Nuove Musiche in 1601.

The rise of instrumental monody did not have its roots exclusively in vocal music. In part, it was based on the extant sixteenth-century practice of performing polyphonic madrigals with one voice singing the treble line, while the others were played by instruments or by a single keyboard instrument. Thus, while all voices were still theoretically equal in these polyphonic compositions, in practice the listener would have heard one voice as being a melody and the others as accompaniment. Furthermore, the new musical genres that appeared in the late sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries, especially the instrumental sonata, revealed a transition in ways of thinking about composition and performance, from a collaboration of equals to a soloist backed up by a relatively unimportant accompaniment. In addition, even in the mid sixteenth century, most works for voice and lute were conceived specifically as such. In the realm of English ayres, for instance, this meant that composers such as John Dowland and Adrian Le Roy were already thinking of a dichotomous melody and bass, filled in not with counterpoint but with chords “planned for harmonic effect.”

A third major difference between Renaissance and Baroque music lies in which instruments were favored and used in performance. This is directly related to a larger shift in musical aesthetics, again stemming chiefly from the Florentine Camerata. In his Dialogo della musica antica e della moderna, Vincenzo Galilei, like Bardi, lauds the music of the Greeks, convinced that their music had “virtuous and wonderful effects” on listeners, while saying that modern composers did not know how to “express the conceptions of the mind [or] how to impress them with the greatest possible effectiveness on the minds of the listeners.” The idea that music could and ought to move or impress listeners and provoke certain archetypal emotional states evidenced a change in thinking about music. This went hand-in-hand with the transition from polyphony to monody discussed above, for a solo instrument or pair of instruments would ideally be not only be the sole melodic vehicle but also be capable of “impressing [the listeners] with the greatest possible effectiveness.”

This necessarily led to a change in the types of instruments that were preferred by composers, for many instruments of the Renaissance were greatly limited in pitch range, being designed only to play a discreet role in a consort of instruments, as well as in dynamic scope. Entire families of instruments, such as racketts and shawms, were unsuited to carrying a solo melodic line with brilliance and expressiveness because they were incapable of dynamic variation, and fell into disuse or at best provided color in string-dominated ensembles. The low instruments of the woodwind consorts were all but abandoned. Even in the string family, members of the viol family – except for the bass viol which provided the necessary basso continuo – were gradually replaced by the new and highly virtuosic violin. The lute and viola da gamba continued being written for in an accompanimental role but could not compete with the violin in volume. The shawm was replaced by the oboe, which had a more refined sound and was capable of dynamic nuance. The cornett, which in the Renaissance tended to function as the soprano member of the sackbut family, survived in the early seventeenth century as a solo instrument, even having a large repertoire rivaling that of the violin, but eventually disappeared as well. However, Renaissance instruments did not vanish from use quickly; contemporary references indicate such instruments survived in chamber or military contexts well throughout the seventeenth century and even into the eighteenth.

As a general rule, however, one can see in the Baroque an overwhelming preference for those instruments that were capable of carrying a melodic line alone: those that were louder and higher, that could achieve a variety of dynamics, and that lent themselves to virtuosic display and emotional expression, none of which the Renaissance instruments were designed to do. Lower-pitched instruments, those that could not vary dynamics, or those that were cumbersome, were deprecated. Thus, the supremacy of melody in the Baroque mind had wide-reaching consequences in the instrumental choices made by composers and makers.

A change between Renaissance and Baroque styles can also be discerned in the realm of orchestration, or instrumental groupings. As has been discussed above, instruments in the sixteenth century were grouped together, either as fixed (“whole”) or broken (mixed) consorts: fixed consorts consisting of instruments from the same family (such as recorders or viols) or broken being a combination of instruments from different families (like the English consort), with or without voice. As the century went on, small mixed consorts of unlike instruments remained the norm.

Regardless of the type of ensemble, a heterogeneous texture prevailed in these ensembles and in the works they played; each member of the ensemble had a distinct part in the texture, which they played through from beginning to end. In the late sixteenth century, however, Andrea and Giovanni Gabrieli at St Mark’s Basilica in Venice began experimenting with placing diverse group of performers – instrumental and vocal – in antiphonal locations around the vast interior of the church, in what became known as cori spezzati (divided choirs).

Such music allowed for highly dramatic effects, with sudden shifts in volume, articulation, timbre and texture, for not all of the choirs were the same size, and could be made up of radically different combinations of voices and instruments. With the addition of the basso continuo in the early seventeenth century, the concertato style (stile concertato) had essentially been developed, featuring a larger overarching ensemble out of which smaller groups were selected at will to play successive musical phrases in different styles, or to perform simultaneously in different manners. Thus, one phrase might be soloistic, the next set in imitative polyphony, the next homophonic, the next an instrumental tutti, and so on. Alternatively, a chorus could declaim a text homophonically while violins played in an entirely different style at the same time – in a different register, in a different location in the church, all performed over a basso continuo. The stile concertato spread throughout Europe and was particularly dominant in Italy and Germany, later forming the basis of the Baroque concerto, the concerto grosso, and the German cantata.

The above playlist contains selected works by some of the composers covered in the remainder of this chapter. The numbers that appear before the names of compositions in the text below refer to their position in the playlist. There will also be separate playlists for each composer which contain all the recordings available on Spotify barring those that are arrangements for modern instruments, instrumental arrangements of pieces originally scored for voices and the like.

Composers of the Early Baroque

Giulio Romolo Caccini (also Giulio Romano) (8 October 1551 – buried 10 December 1618) was an Italian composer, teacher, singer, instrumentalist and writer of the late Renaissance and early Baroque eras. He was one of the founders of the genre of opera, and one of the most influential creators of the new Baroque style.

The stile recitativo, as the newly created style of monody was called, proved to be popular not only in Florence, but elsewhere in Italy. Florence and Venice were the two most progressive musical centers in Europe at the end of the 16th century, and the combination of musical innovations from each place resulted in the development of what came to be known as the Baroque style. Caccini’s achievement was to create a type of direct musical expression, as easily understood as speech, which later developed into the operatic recitative, and which influenced numerous other stylistic and textural elements in Baroque music.

Caccini wrote music for three operas—Euridice (1600), Il rapimento di Cefalo (1600, excerpts published in the first Nuove musiche), and Euridice (1602), though the first two were collaborations with others (mainly Peri for the first Euridice). In addition he wrote the music for one intermedio (Io che dal ciel cader farei la luna) (1589). No music for multiple voices survives, even though the records from Florence indicate he was involved with polychoral music around 1610.

He was predominantly a composer of monody and solo song accompanied by a chordal instrument (he himself played harp), and it is in this capacity that he acquired his immense fame. He published two collections of songs and solo madrigals, both titled Le nuove musiche, in 1602 (new style) and 1614 (the latter as Nuove musiche e nuova maniera di scriverle). Most of the madrigals are through-composed and contain little repetition; some of the songs, however, are strophic. Among the most famous and widely disseminated of these is the madrigal Amarilli, mia bella.

- L’Euridice, Act 1, Scene 2: Cruda morte

- L’Euridice, Act 1, Scene 3: Se de’ boschi i verdi onori

- L’Euridice, Act 3, Scene 5: Biondo arciere che d’alto monte Aureo fonte

- Amarilli, mia bella

Giovanni Gabrieli (c. 1554/1557 – 12 August 1612) was an Italian composer and organist. He was one of the most influential musicians of his time, and represents the culmination of the style of the Venetian School, at the time of the shift from Renaissance to Baroque idioms.

Though Gabrieli composed in many of the forms current at the time, he preferred sacred vocal and instrumental music. All of his secular vocal music was composed relatively early in his career; he never wrote lighter forms, such as dances; and later he concentrated on sacred vocal and instrumental music that exploited sonority for maximum effect. Among the innovations credited to him – and while he was not always the first to use them, he was the most famous of his period to do so – were dynamics; specifically notated instrumentation (as in the famous Sonata pian’ e forte); and massive forces arrayed in multiple, spatially separated groups, an idea which was to be the genesis of the Baroque concertato style, and which spread quickly to northern Europe, both by the report of visitors to Venice and by Gabrieli’s students, which included Hans Leo Hassler and Heinrich Schütz.

Like composers before and after him, he would use the unusual layout of the San Marco church, with its two choir lofts facing each other, to create striking spatial effects. Most of his pieces are written so that a choir or instrumental group will first be heard on one side, followed by a response from the musicians on the other side; often there was a third group situated on a stage near the main altar in the centre of the church. While this polychoral style had been extant for decades (Adrian Willaert may have made use of it first, at least in Venice), Gabrieli pioneered the use of carefully specified groups of instruments and singers, with precise directions for instrumentation, and in more than two groups. The acoustics were and are such in the church that instruments, correctly positioned, could be heard with perfect clarity at distant points. Thus instrumentation which looks strange on paper, for instance, a single string player set against a large group of brass instruments, can be made to sound, in San Marco, in perfect balance. A fine example of these techniques can be seen in the scoring of In Ecclesiis.

Gabrieli’s first motets were published alongside his uncle Andrea’s compositions in his 1587 volume of Concerti. These pieces show much influence of his uncle’s style in the use of dialogue and echo effects. There are low and high choirs and the difference between their pitches is marked by the use of instrumental accompaniment. The motets published in Giovanni’s 1597 Sacrae Symphoniae seem to move away from this technique of close antiphony towards a model in which musical material is not simply echoed, but developed by successive choral entries. Some motets, such as Omnes Gentes developed the model almost to its limits. In these motets, instruments are an integral part of the performance, and only the choirs marked “Capella” are to be performed by singers for each part.

There seems to be a distinct change in Gabrieli’s style after 1605, the year of publication of Monteverdi’s Quinto libro di madrigali, and Gabrieli’s compositions are in a much more homophonic style as a result. There are sections purely for instruments – called “Sinfonia” – and small sections for soloists singing florid lines, accompanied simply by a basso continuo. “Alleluia” refrains provide refrains within the structure, forming rondo patterns in the motets, with close dialogue between choirs and soloists. In particular, one of his best-known pieces, In Ecclesiis, is a showcase of such polychoral techniques, making use of four separate groups of instrumental and singing performers, underpinned by the omnipresent organ and continuo.

- O quad suavis a 7, C. 10

- O Jesu mi dolcissima, C. 24

- Three Mass Movements: Sanctus-Benedictus: Kyrie

- O Jesu mi dolcissima, C. 56

- Kyrie, C. 71-73

- In ecclesiis, C. 78

- Lieto godea sedendo, C. 113

- Canzoni septimi toni

- Canzon primi toni a 10, C.176

- Canzoni et sonate: Sonata XIX a 15

Jacopo Peri (20 August 1561 – 12 August 1633) was an Italian composer, singer and instrumentalist of the late Renaissance and early Baroque periods. He wrote what is considered the first opera, the mostly lost Dafne (c. 1597), and also the earliest extant opera, Euridice (1600). Peri produced a number of other operas, often in collaboration with other composers (such as La Flora with Marco da Gagliano), and also wrote a number of other pieces for various court entertainments. Few of his pieces are still performed today, and even by the time of his death, his operatic style was looking rather old-fashioned when compared to the work of relatively younger reformist composers such as Claudio Monteverdi. Peri’s influence on those later composers, however, was large.

- Euridice, Scena II: Poi che gli eterni imperi

- Euridice, Scena III: Biond’arcier che d’alto monte

Jan Pieterszoon Sweelinck April or May, 1562 – 16 October 1621) was a Dutch composer, organist, and pedagogue whose work straddled the end of the Renaissance and beginning of the Baroque eras. He was among the first major keyboard composers of Europe, and his work as a teacher helped establish the north German organ tradition.

Sweelinck represents the highest development of the Dutch keyboard school, and indeed represented a pinnacle in keyboard contrapuntal complexity and refinement before J.S. Bach. However, he was a skilled composer for voices as well, and composed more than 250 vocal works (chansons, madrigals, motets and Psalms).

Some of Sweelinck’s innovations were of profound musical importance, including the fugue—he was the first to write an organ fugue which began simply, with one subject, successively adding texture and complexity until a final climax and resolution. It is also generally thought that many of Sweelinck’s keyboard works were intended as studies for his pupils. He was also the first to use the pedal as a real fugal part. Stylistically Sweelinck’s music also brings together the richness, complexity and spatial sense of Andrea and Giovanni Gabrieli, and the ornamentation and intimate forms of the English virginalists. In some of his works Sweelinck appears as a composer of the Baroque style, with the exception of his chansons which mostly resemble the French Renaissance tradition. In formal development, especially in the use of countersubject, stretto, and organ point (pedal point), his music could be said to resemble Bach (who was quite possibly familiar with Sweelinck’s music).

Sweelinck was a master improviser, and acquired the informal title of the “Orpheus of Amsterdam”. More than 70 of his keyboard works have survived, and many of them may be similar to the improvisations that residents of Amsterdam around 1600 were likely to have heard. In the course of his life, Sweelinck was involved with the musical liturgies of three distinctly different traditions: Catholic, the Calvinist, and Lutheran—all of which are reflected in his work. Even his vocal music, which is more conservative than his keyboard writing, shows a striking rhythmic complexity and an unusual richness of contrapuntal devices.

- Fantasia chromatica (d1), SwWV 258

- Sine cerere et Baccho friget Venus (I)

Hans Leo Hassler (baptized 26 October 1564 – 8 June 1612) was a German composer and organist of the late Renaissance and early Baroque eras. He was one of the first to bring the innovations of the Venetian style across the Alps. Through his songs, “in the manner of foreign madrigal and canzonets,” and the Lustgarten, Hassler brought to Germany the villanelle, canzonette, and dance songs of Gastoldi and Orazio Vecchi. As the first great German composer to undertake an “Italian Journey,” Hassler’s influence was one of the reasons for the Italian domination over German music and for the common trend of German musicians finishing their education in Italy. While musicians of the stature of Lassus had been working in Germany for years, they represented the older school, the prima pratica, the fully developed and refined Renaissance style of polyphony; in Italy new trends were emerging which were to define what was later called the Baroque era. Musicians such as Hassler, and later Schütz, carried the concertato style, the polychoral idea, and the freely emotional expression of the Venetians into the German culture, creating the first and most important Baroque development outside of Italy.

Though Hassler was Protestant, he wrote many masses and directed the music for Catholic masses in Augsburg. While in the service of Octavian Fugger, Hassler dedicated both his Cantiones sacrae and a book of masses for four to eight voices to him. Due to the demands of the Catholic patrons, and his own Protestant beliefs, Hassler’s compositions represented a skillful blend of both religions’ music styles that allowed his compositions to function in both contexts. Thus, many of Hassler’s works could be used both in the Roman Catholic Church and the Lutheran. During his time in Augsburg, Hassler only produced two works that were specifically meant for the Lutheran church. Under the commission of the free city of Nuremberg, the Psalmen simpliciter was composed in 1608, and was dedicated to the city. Hassler also produced the Psalmen und christliche Gesänge, mit vier Stimmen auf die Melodeien fugweis komponiert in 1607 and dedicated it to Elector Christian II of Saxony. Stylistically, Hassler’s early works exhibit reflections of the influence of Lassus, while his later works are marked by the impressions left on him by his studies in Italy. After returning from Italy, Hassler incorporated polychoral techniques, textural contrasts and occasional chromaticism in his compositions. His later masses were characterized by light melodies juxtaposed with the grace and fluidity of the madrigalian dance songs; thus creating a charming sacred style that was more sonorous than it was profound. His secular music—madrigals, canzonette, and songs among the vocal, and ricercars, canzonas, introits and toccatas among the instrumental—show many of the advanced techniques of the Gabrielis in Italy, but with a somewhat more restrained character, and always attentive to craftsmanship and beauty of sound. However, Hassler’s greatest success in combining the German and Italian compositional styles existed in his lieder. In 1590, Hassler released his first publication, a set of twenty-four, four-part canzonette. The Lustgarten neuer teutscher Gesang, Balletti, Galliarden und Intraden, which contains thirty-nine vocal and eleven instrumental pieces, is Hassler’s most renowned collection of lieder. Within this work, Hassler published dance collections for four, five, or six string or wind instruments with voice and without continuo. He also composed Mein G’müt ist mir verwirret, a five-part piece. Its melody was later combined with the text O Haupt voll Blut und Wunden of Paul Gerhardt, in which form it was used by Bach in his St Matthew Passion. Bach also employed the melody as a counterpoint to the aria Komm, du süße Todesstunde in Cantata 161 and used it once again as the final chorale in that same cantata.

Along with many of his contemporaries, Hassler sought to blend the Italian virtuoso style with the traditional style prevalent in Germany. This was accomplished in the chorale motet by employing the thorough bass continuo and including instrumental and solo ornamentation. Hassler’s motets exhibit this blend of the old and the new in the way they reflect both the influence of Lassus and the two four-part chorus style of the Gabrielis.

Hassler is considered to be one of the most important German composers of all time. His use of the innovative Italian techniques, coupled with traditional, conservative German techniques allowed his compositions to be fresh without the modern affective tone. His songs presented a combined vocal and instrumental literature that did not make use of the continuo, or only provided it as an option, and his sacred music introduced the Italian polychoral structures that would later influence many composers leading into the Baroque era.

- Allein Gott in der Höh sei Ehr

- Si bona suscepimus à 8

- Lustgarten neuer teutscher Gesäng, Balletti, Galliarden und Intraden: No. 5 Ach Schatz, Ich Sing Und Lache

- Lustgarten neuer teutscher Gesäng, Balletti, Galliarden und Intraden: Galliarde: All Lust Und Freud

Claudio Giovanni Antonio Monteverdi (baptized 15 May 1567 – 29 November 1643) was an Italian composer, choirmaster and string player. A composer of both secular and sacred music, and a pioneer in the development of opera, he is considered a crucial transitional figure between the Renaissance and Baroque periods of music history.

Much of Monteverdi’s output, including many stage works, has been lost. His surviving music includes nine books of madrigals, large-scale religious works, such as his Vespro della Beata Vergine (Vespers for the Blessed Virgin) of 1610, and three complete operas. His opera L’Orfeo (1607) is the earliest of the genre still widely performed; towards the end of his life he wrote works for Venice, including Il ritorno d’Ulisse in patria and L’incoronazione di Poppea.

While he worked extensively in the tradition of earlier Renaissance polyphony, as evidenced in his madrigals, he undertook great developments in form and melody, and began to employ the basso continuo technique, distinctive of the Baroque. No stranger to controversy, he defended his sometimes novel techniques as elements of a seconda pratica, contrasting with the more orthodox earlier style which he termed the prima pratica. Largely forgotten during the eighteenth and much of the nineteenth centuries, his works enjoyed a rediscovery around the beginning of the twentieth century. He is now established both as a significant influence in European musical history and as a composer whose works are regularly performed and recorded.

- Vespro della Beata Vergine, SV 206: Invitatorium: versiculum et responsorium Deus in adjutorium (1610)

- Vespro della Beata Vergine, SV 206: Concerto “Duo Seraphim”

- Vespro della Beata Vergine, SV 206: Psalmus “Nisi Dominus”

- Vespro della Beata Vergine, SV 206: Gloria Patri

- Vespro della Beata Vergine, SV 206: Sicut erat

- Vespro della Beata Vergine, SV 206: Conclusio: versiculum et responsorium Domine, exaudi orationem meam

- Beatus vir primo, SV 268 (1630)

- Zefiro torna, e di soavi accenti, SV 251 (1632)

- Selva morale e spirituale: No. 8, Crucifixus, SV 259 (1641)

- Selva morale e spirituale: No. 27, Sanctorum meritis II, SV 278

- L’incoronazione di Poppea: Act 3, scene 8: Coro di Amori: “Or cantiamo giocondi” (1643)

- L’incoronazione di Poppea: Act 3: “Pur ti miro”

- Messa, salmi concertate et letanie: No. 9, Laetatus sum I, SV 198 (1650)

Michael Praetorius (probably 28 September 1571 – 15 February 1621) was a German composer, organist, and music theorist. He was one of the most versatile composers of his age, being particularly significant in the development of musical forms based on Protestant hymns.

Praetorius was a prolific composer; his compositions show the influence of Italian composers and his younger contemporary Heinrich Schütz. His works include the 17 volumes of music published during his time as Kapellmeister to Duke Heinrich Julius of Wolfenbüttel, between 1605 and 1613. His nine-part Musae Sioniae (1605–10) was a collection of chorales and vernacular music for the Lutheran service for 2 to 16 voices; he also published an extensive collection of Latin music for the church service (Liturgodiae Sioniae). Terpsichore, a compendium of more than 300 instrumental dances is his most widely known and recorded work today; it is his sole surviving secular work from a projected multi-volume collection (Musae Aioniae).

Many of Praetorius’ choral compositions were scored for several smaller choirs situated in several locations in the church, in the style of the Venetian polychoral music of Gabrieli.

- Musae Sioniae V: Vom Himmel hoch, da komm ich her (1607)

- Musae Sioniae V: In dulci jubilo (1607)

- Musae Sioniae IX: Joseph, lieber Joseph mein (1610)

- Terpsichore: Bransles de la torch à 5

- Terpsichore: a. Ballet des Baccanales b. Ballet des feus c. Ballet des Matelotz

- Terpsichore: La Sarabande

- Terpsichore: Introduction and Courante

- Terpsichore: Ballet

- Terpsichore: Volte

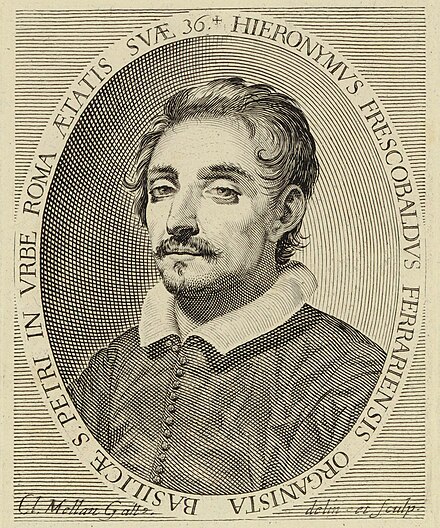

Girolamo Alessandro Frescobaldi (September 1583 – 1 March 1643) was an Italian composer and virtuoso keyboard player. Born in the Duchy of Ferrara, he was one of the most important composers of keyboard music in the late Renaissance and early Baroque periods. A child prodigy, Frescobaldi studied under Luzzasco Luzzaschi in Ferrara, but was influenced by many composers, including Ascanio Mayone, Giovanni Maria Trabaci, and Claudio Merulo. Girolamo Frescobaldi was appointed organist of St. Peter’s Basilica, a focal point of power for the Cappella Giulia (a musical organisation), from 21 July 1608 until 1628 and again from 1634 until his death.

Frescobaldi’s printed collections contain some of the most influential music of the 17th century. His work influenced Johann Jakob Froberger, Johann Sebastian Bach, Henry Purcell, and other major composers. Pieces from his celebrated collection of liturgical organ music, Fiori musicali (1635), were used as models of strict counterpoint as late as the 19th century.

Frescobaldi was, after Jan Pieterszoon Sweelinck, the first of the great composers of the ancient Franco-Netherlandish-Italian tradition who chose to focus his creative energy on instrumental composition. Frescobaldi brought a wide range of emotion to the relatively unplumbed depths of instrumental music. Keyboard music occupies the most important position in Frescobaldi’s extant oeuvre. He published eight collections of it during his lifetime, several were reprinted under his supervision, and more pieces were either published posthumously or transmitted in manuscripts. His collection of instrumental ensemble canzonas, Il Primo Libro delle Canzoni, was published in two editions in Rome in 1628, and substantially revised in the Venice edition of 1634. Of the forty pieces in the collection, ten were replaced and all were revised to various degrees, sixteen of them radically so. This extensive editing attests to Frescobaldi’s ongoing interest in the utmost perfection of his pieces and collections.

Frescobaldi’s compositional canon began with his 1615 publications. One of the publications issued in 1615 was Ricercari, et canzone. This work returned to the old-fashioned, pure style of ricercar. Fast note values and triple meter were not allowed to detract from the purity of style. A second publication of 1615 was the Toccate e partite which established expressive keyboard style. Frescobaldi did not obey the conventional rules for composing, ensuring no two works have a similar structure. From 1615 to 1628, Frescobaldi’s publications connect him with the Congregazione exactly when the group’s activities determined the Roman musical trends.

Frescobaldi’s next stream of compositions expanded their artistic range beyond the keyboard music that he had focused on previously. Frescobaldi’s next four publications after 1627 were composed for instrumental and vocal ensembles in both sacred and secular genres. The collections of thirty sacred works of 1627 and forty ensemble canzonas of 1628 are structural opposites. However, both are written in a more traditional style that makes them appropriate for church use. The Arie musicali, published in 1630, were probably composed earlier while Frescobaldi was in Rome. These two volumes utilize keyboard pairs, the romanesca/ruggiero and the ciaconna/passacaglia, within the vocal mode.

In 1635, Frescobaldi published Fiori musicali. This group of works is his only composition devoted to church music and his last collection containing completely new pieces. The Fiori experiments with many types of genres within the liturgical confines of a mass. Almost all of the genres practiced by Frescobaldi are present within this collection except for the popular style. Frescobaldi cultivated the old form of organ improvisation on a Gregorian chant cantus firmus that is best displayed within the Fiori muscali. The organ alternated with the choir on versets and improvised in a contrapuntal style. Works from Fiori musicali were still used as models of strict counterpoint in the 18th and 19th centuries.

Aside from Fiori musicali, Frescobaldi’s two books of toccatas and partitas (1615 and 1627) are his most important collections. His toccatas could be used in masses and liturgical occasions. These toccatas served as preludes to larger pieces, or were pieces of substantial length standing alone. The Secondo libro, written in 1627, stretches the conception of the genres included in the first book of toccatas. More variety is introduced with different rhythmic techniques and four organ pieces. Both books open with a set of twelve toccatas written in a flamboyant improvisatory style and alternating fast-note runs or passaggi with more intimate and meditative parts, called affetti, plus short bursts of contrapuntal imitation.

Virtuosic techniques permeate the music and make some of the pieces challenging even for modern performers—Toccata IX from Secondo libro di toccata bears an inscription by the composer: “Non senza fatiga si giunge al fine”, “Not without toil will you get to the end.” Such short remarks appear also in works from Fiori musicali; one of these refers to a fifth voice that is to be sung by the performer at key moments during a ricercar, and the key moments are left to the performer to find. Frescobaldi’s famous note for this piece is “”Intendami chi puo che m’intend’ io”—”Understand me, [who can,] as long as I can understand myself”. The concept is yet another illustration of Frescobaldi’s innovative, bold approach to composition.

Although Frescobaldi was influenced by numerous earlier composers such as the Neapolitans Ascanio Mayone and Giovanni Maria Trabaci and the Venetian Claudio Merulo, his music represents much more than a summary of its influences. Aside from his masterful treatment of traditional forms, Frescobaldi is important for his numerous innovations, particularly in the field of tempo: unlike his predecessors, he would include in his pieces sections in contrasting tempi, and some of his publications include a lengthy preface detailing tempo-related aspects of performance. In effect, he made a compromise between the ancient white mensural notation with a rigid tactus and the modern notion of tempo. Although this idea was not new (it was used by, for example, Giulio Caccini), Frescobaldi was among the first to popularize it in keyboard music.

Frescobaldi also made substantial contributions to the art of variation; he may have been one of the first composers to introduce the juxtaposition of the ciaccona and passacaglia into the music repertory, as well as the first to compose a set of variations on an original theme (all earlier examples are variations on folk or popular melodies). Frescobaldi showed an increasing interest in composing intricate works out of unrelated individual pieces during his last years of composing. The last work Frescobaldi composed, Cento partite sopra passacagli, was his most impressive creative work. The Cento displays Frescobaldi’s new interest in combining different pieces that were first written independently.

The composer’s other works include collections of canzonas, fantasias, capriccios, and other keyboard genres, as well as four prints of vocal music (motets and arias; one book of motets is lost) and one of ensemble canzonas.

- Messa della Madonna: Recercar con obligo di Cantare la Quinta parte senza Tocarla

- Messa della Madonna: Capriccio sopra la Girolmeta

- Il primo libro di toccate d’intavolatura de Cembalo e organo

- Ego sum qui sum, F 11.28

- De ore prudentis procedit mel, F 11.7 – a 2 soprani

- Missa sopra l’aria della monica: Sanctus

Orlando Gibbons (bapt. 25 December 1583 – 5 June 1625) was an English composer and keyboard player who was one of the last masters of the English Virginalist School and English Madrigal School. The best known member of a musical family dynasty, by the 1610s he was the leading composer and organist in England, with a career cut short by his sudden death in 1625. As a result, Gibbons’s oeuvre was not as large as that of his contemporaries, like the elder William Byrd, but he made considerable contributions to many genres of his time. He is often seen as a transitional figure from the Renaissance to the Baroque periods.

His oeuvre as a whole suggests he was comfortable composing in the genres he had established himself in, rarely adventuring to unexplored genres. Gibbons wrote a large number of keyboard works, around thirty fantasias for viols, a number of madrigals (the best-known being “The Silver Swan”), and many popular verse anthems, all to English texts (the best known being “Great Lord of Lords”). Perhaps his best-known verse anthem is “This Is the Record of John”, which sets an Advent text for solo countertenor or tenor, alternating with full chorus. The soloist is required to demonstrate considerable technical facility, and the work expresses the text’s rhetorical force without being demonstrative or bombastic. He also produced two major settings of Evensong, the Short Service and the Second Service, an extended composition combining verse and full sections. Gibbons’s full anthems include the expressive O Lord, in thy wrath, and the Ascension Day anthem “O clap your hands together” (after Psalm 47) for eight voices.

Gibbons’s surviving keyboard output comprises some 45 pieces. The polyphonic fantasia and dance forms are the best represented genres. Gibbons’s writing exhibits a command of three- and four-part counterpoint. Most of the fantasias are complex, multi-sectional pieces, treating multiple subjects imitatively. Gibbons’s approach to melody, in both his fantasias and his dances, features extensive development of simple musical ideas, as for example in Pavane in D minor and Lord Salisbury’s Pavan and Galliard.

- O Thou, the Central Orb (1619)

- Second Service: Jubilate

- Second Service: Magnificat

Heinrich Schütz (18 October 1585 – 6 November 1672) was a German composer and organist, generally regarded as the most important German composer before Johann Sebastian Bach and one of the most important composers of the 17th century. He is credited with bringing the Italian style to Germany and continuing its evolution from the Renaissance into the early Baroque. Most of his surviving music was written for the Lutheran church, primarily for the Electoral Chapel in Dresden. He wrote what is traditionally considered the first German opera, Dafne, performed at Torgau in 1627, the music of which has since been lost, along with nearly all of his ceremonial and theatrical scores. Schütz was a prolific composer, with more than 500 surviving works.

Schütz’s compositions show the influence of Gabrieli (most notably in Schütz’s use of polychoral and concertato styles) and Monteverdi. The influence of the Netherlandish composers of the 16th century is also prominent in his work. His best-known works are sacred, ranging from solo voice with instrumental accompaniment to a cappella choral music. Representative works include his Psalmen Davids (Psalms of David, Opus 2), Cantiones sacrae (Opus 4), three books of Symphoniae sacrae, Die sieben Worte Jesu Christi am Kreuz (The seven words of Jesus Christ on the Cross), three Passion settings, and the Christmas Story. Schütz’s music, while in the most progressive styles early in his career, eventually grew simple and almost austere, culminating in his late Passion settings. Practical considerations were certainly responsible for part of this change: the Thirty Years’ War devastated Germany’s musical infrastructure, and it was no longer practical or even possible to put on the gigantic works in the Venetian style of his earlier period.

Schütz’s composition “Es steh Gott auf” (SWV 356) is in many respects comparable to Monteverdi. His funeral music “Musikalische Exequien” (1636) for his noble friend Heinrich Posthumus of Reuss is considered a masterpiece, and is known today as the first German Requiem. Schütz was equally fluent in Latin and Germanic styles.

Schütz was one of the last composers to write in a modal style. His harmonies often result from the contrapuntal alignment of voices rather than from any sense of “harmonic motion”; contrastingly, much of his music shows a strong tonal pull when approaching cadences. His music includes a great deal of imitation, but structured in such a way that the successive voices do not necessarily enter after the same number of beats or at predictable intervallic distances. This contrasts sharply with the manner of his contemporary Johann Hermann Schein and Samuel Scheidt, whose counterpoint usually flows in regularly spaced entries. Schütz’s writing often includes intense dissonances caused by the contrapuntal motion of voices moving in correct individual linear motion but resulting in startling harmonies. Above all, his music displays extreme sensitivity to the accents and meaning of the text, which is often conveyed using special technical figures drawn from musica poetica, themselves drawn from or created in analogy to the verbal figures of classical rhetoric. As noted above, Schütz’s style became simpler in his later works, which make less frequent use of the kind of distantly related chords and licences found in such pieces as “Was hast du verwirket” (SWV 307) from Kleine geistliche Konzerte II.

Beyond the early book of madrigals, almost no secular music by Schütz has survived, save for a few domestic songs (arien) and occasional commemorative items (such as Wie wenn der Adler sich aus seiner Klippe schwingt (SWV 434), and no purely instrumental music at all (unless one counts the short instrumental movement, “sinfonia”, that encloses the dialogue of Die sieben Worte), even though he had a reputation as one of Germany’s finest organists.

Schütz was of great importance in bringing new musical ideas to Germany from Italy, and thus had a large influence on the German music which was to follow. The style of the North German organ school derives largely from Schütz (as well as from the Dutchman Jan Pieterszoon Sweelinck); a century later this music culminated in the work of J.S. Bach. After Bach, the most important composers Schütz influenced were Anton Webern and Brahms, who studied his work.

- Becker Psalter, Op. 5: No. 85, Wie sehr lieblich und schöne sind doch die Wohnung dein, SWV 181 “Psalm 84” (1628)

- Symphoniae sacrae I, Op. 6: No. 9, O quam tu pulchra es, amica mea, SWV 265 (1629)

- Musikalische Exequien, Op. 7, SWV 279-281: I. Concert in Form einer deutschen Bergräbnis-Missa. Herr, ich lasse dich nicht (1636)

- Symphoniae sacre II, Op. 10, SWV 341-367: III. Herr unser Herrscher, wie herrlich ist dein Name (1647)

- Symphoniae sacre II, Op. 10, SWV 341-367: XVI. Es steh Gott auf (1647)

- Historia der Geburt Jesu Christi, SWV 435: No. 5, Intermedium II. Die Menge der Engel (1664)

Andrea Falconieri (1585 or 1586 – 1656), also known as Falconiero, was an Italian composer and lutenist from Naples. He was an adept composer of both vocal and instrumental works. During his long music career, Falconieri came in contact with various vocal and instrumental traditions from Italy and Spain. His compositions reflect these influences, being characterized by dance rhythms, instrumental virtuosity and the new monodic vocal style.

- Il primo libro di canzone, sinfonie, fantasie, capricci, brandi, correnti, gagliarde, alemane, volte: “La suave melodia” (1650)

- Il primo libro di canzone, sinfonie, fantasie, capricci, brandi, correnti, gagliarde, alemane, volte: No. 15, Passacalle

Johann Hermann Schein (20 January 1586 – 19 November 1630) was a German composer of the early Baroque era. He was Thomaskantor in Leipzig from 1615 to 1630. He was one of the first to import the early Italian stylistic innovations into German music, and was one of the most polished composers of the period.

Schein was one of the first to absorb the innovations of the Italian Baroque—monody, the concertato style, figured bass—and use them effectively in a German Lutheran context. While Schütz made more than one trip to Italy, Schein apparently spent his entire life in Germany, making his grasp of the Italianate style all the more remarkable. His early concertato music seems to have been modeled on Lodovico Grossi da Viadana’s Cento concerti ecclesiastici, which were available in an edition prepared in Germany.

Unlike Schütz, who concentrated mainly on sacred music (although it must be borne in mind that at least two operas composed by him, among other secular works, have been lost), Schein wrote sacred and secular music in approximately equal quantities, and almost all of it was vocal. In his secular vocal music he wrote all of his own texts. Throughout his life he published alternating collections of sacred and secular music, in accordance with an intention he stated early on — in the preface to the Banchetto musicale — to publish alternately music for use in worship and social gatherings. The contrast between the two kinds of music can be quite extreme. While some of his sacred music uses the most sophisticated techniques of the Italian madrigal for a devotional purpose, such as the motet Wie lieblich sind deine Wohnungen setting verses from Psalm 84, several of his secular collections include such things as drinking songs of a surprising simplicity and humor. Some of his works attain an expressive intensity matched in Germany only by those of Schütz, for example the spectacular Fontana d’Israel or Israel’s Brünnlein (1623), in which Schein declared his intent to exhaust the possibilities of German word-painting “in the style of the Italian madrigal.”

Possibly his most famous collection was his only collection of instrumental music, the Banchetto musicale (Musical banquet) (1617) which contains twenty separate variation suites; they are among the earliest, and most perfect, representatives of the form. Most likely they were composed as dinner music for the courts of Weissenfels and Weimar, and were intended to be performed on viols. They consist of dances: a pavan-galliard (a normal early Baroque pair), a courante, and then an allemande-tripla. Each suite in the Banchetto is unified by mode as well as by theme.

- Musica boscareccia: Concordia zu jeder Zeit (1621-1628)

- Musica boscareccia: Als Filli zart einst etwas durstig ward (1621-1628)

- Musica boscareccia: O Luft, du edles Element (1621-1628)

- Fontana d’Israel, Israelis Brünnlein: No. 11, Lieblich und schöne sein ist nichts (1623)

Samuel Scheidt (baptised 3 November 1587 – 24 March 1654) was a German composer, organist and teacher of the early Baroque era. Scheidt was the first internationally significant German composer for the organ, and represents the flowering of the new north German style, which occurred largely as a result of the Protestant Reformation. In south Germany and some other countries of Europe, the spiritual and artistic influence of Rome remained strong, so most music continued to be derivative of Italian models. Cut off from Rome, musicians in the newly Protestant areas readily developed styles that were much different from those of their neighbors.

Scheidt’s music is in two principal categories: instrumental music, including a large amount of keyboard music, mostly for organ; and sacred vocal music, some of which is a cappella and some of which uses a basso continuo or other instrumental accompaniment. In his numerous chorale preludes, Scheidt often used a “patterned variation” technique, in which each phrase of the chorale uses a different rhythmic motive, and each variation is more elaborate than the previous one, until the climax of the composition is reached. In addition to his chorale preludes, he wrote numerous fugues, suites of dances (which were often in a cyclic form, sharing a common ground bass) and fantasias.

- Courante

- Tablatura Nova, Pt. 1: No. 2 Fantasia super. Jo son fertio lasso, quadruplici (1624)