Your cart is currently empty!

A History of Western Art Music

Chapter Three: The High Renaissance

In the early 1470s, music started to be printed using a printing press. Music printing had a major effect on how music spread for not only did a printed piece of music reach a larger audience than any manuscript ever could, it did it far more cheaply as well. Also during this century, a tradition of famous makers began for many instruments. These makers were masters of their craft. An example is Neuschel for his trumpets.

Towards the end of the fifteenth century, polyphonic sacred music (as exemplified in the masses of Johannes Ockeghem and Jacob Obrecht) had once again become more complex, in a manner that can perhaps be seen as correlating to the increased exploration of detail in painting at the time. Ockeghem, particularly, was fond of canon, both contrapuntal and mensural. He composed a mass, Missa prolationum, in which all the parts are derived canonically from one musical line.

In the early sixteenth century, there is a trend towards simplification, as can be seen to some degree in the work of Josquin des Prez and his contemporaries in the Franco-Flemish School, then later in that of Palestrina, who was partially reacting to the strictures of the Council of Trent, which discouraged excessively complex polyphony as inhibiting understanding the text. Early sixteenth-century Franco-Flemings moved away from the complex systems of canonic and other mensural play of Ockeghem’s generation, tending toward points of imitation and duet or trio sections within an overall texture that grew to five and six voices. They also began, even before the Tridentine reforms, to insert ever-lengthening passages of homophony, to underline important text or points of articulation.

The above playlist contains selected works by some of the composers covered in the remainder of this chapter. The numbers that appear before the names of compositions in the text below refer to their position in the playlist. There are also separate playlists for each composer which contain all of the recordings available on Spotify barring those that are arrangements for modern instruments, instrumental arrangements of pieces originally scored for voices and the like.

Composers of the High Renaissance (1470–1530)

Colinet de Lannoy (died before 6 February 1497) was a French composer of the Renaissance. He was one of the composers/singers working at the Milan chapel at the time of the assassination of Duke Galeazzo Maria Sforza in 1476, and he possibly also worked in France.

Only two compositions are definitely attributed to Lannoy, both secular songs: Cela sans plus and Adieu natuerlic leven mijn. The former of these was used as a basis for mass settings by other composers, including Johannes Martini and Jacob Obrecht.

One other piece has been considered as a possible composition by Lannoy, a partial cyclic mass for three voices. It is given to “lanoy” in the source, and the style is consistent both with Lannoy’s songs and with that of other composers working at Milan.

Abertijne Malcourt (Albertinus and Malcort are common alternate spellings) (d. before 1519) was a Franco-Flemish priest, tenor singer, and music copyist of the Renaissance, principally active at the end of the 15th century, contemporary with Johannes Ockeghem. He is considered to be the composer most likely to have written the famous chanson Malheur me bat, used as the basis for mass settings by Jacob Obrecht, Josquin des Prez, Alexander Agricola, and Andreas Sylvanus.

Edmund Turges (c.1440-after 1501) thought to be also Edmund Sturges (fl. 1507–1508) was an English Renaissance era composer who came from Petworth. He was ordained by Bishop Ridley in 1550, and joined the Fraternity of St. Nicholas (the London Guild of Parish Clerks) in 1469.

Several works are listed in the name of Turges in the Eton Choirbook, which survived Henry VIII’s Dissolution of the Monasteries between 1536 and 1541. Turges also has a Magnificat extant in the Caius Choirbook, and compositions in the Fayrfax Boke. A Kyrie and Gloria are ascribed to Sturges in the Ritson Manuscript. At least two masses and three Magnificat settings have been lost, as well as eight six-part pieces listed in the 1529 King’s College Inventory.

It is quite possible that his setting of Gaude flore virginali was written with the choir of New College, Oxford in mind, especially since a man by the name of Sturges served as a chaplain in the choir between 1507-08. Its unorthodox vocal scoring for TrTrATB suggests the choral forces found in the college at the time where the boys (16 in total) outnumbered the men (of whom there were likely to have been no more than four).

Loyset Compère (c. 1445 – 16 August 1518) was a Franco-Flemish composer of the Renaissance. Of the same generation as Josquin des Prez, he was one of the most significant composers of motets and chansons of that era, and one of the first musicians to bring the light Italianate Renaissance style to France.

Unlike his contemporaries, Compère seems to have written few masses (at least very few survive). By temperament he seems to have been a miniaturist, and his most popular and numerous works were in the shorter forms of the day primarily chansons and motets. Two stylistic trends are evident in his music: the style of the Burgundian School, which he seems to have learned in his early career before coming to Italy, and the lighter style of the Italian composers current at the time, who were writing frottolas (the light and popular predecessor to the madrigal). Compère had a gift for melody, and many of his chansons became popular; later composers used several as cantus firmi for masses. Occasionally he seems to have given himself a formidable technical challenge and set out to solve it, such as writing quodlibets (an example is Au travail suis, which combines no less than six different tunes written to the same text by different composers).

Compère wrote several works in a unique form, sometimes called a free motet, which combines some of the light elegance of the Italian popular song of the time with the contrapuntal technique of the Netherlanders. Some mix texts from different sources, for instance a rather paradoxical Sile fragor which combines a supplication to the Virgin Mary with a drinking song dedicated to Bacchus. His choice of secular texts tended towards the irreverent and suggestive.

His chansons are his most characteristic compositions, and many scholars of Renaissance music consider them to be his best work. They are for three or four voices, and are in three general categories: Italianate, light works for four a cappella voices, very much like frottolas, with text set syllabically and often homophonically, and having frequent cadences; three-voice works in the Burgundian style, rather like the music of Du Fay; and three-voice motet-chansons, which resemble the medieval motet more than anything else. In these works the lowest voice usually sings a slow-moving cantus firmus with a Latin text, usually from chant, while the upper voices sing more animated parts, in French, on a secular text.

Many of Compère’s compositions were printed by Ottaviano Petrucci in Venice, and disseminated widely; obviously their availability contributed to their popularity. Compère was one of the first composers to benefit from the new technology of printing, which had a profound impact on the spread of the Franco-Flemish musical style throughout Europe. Compère also wrote several settings of the Magnificat (the hymn of praise to the Virgin Mary, from the first chapter of the Gospel of Luke), as well as numerous short motets.

- Missa Galeazescha: Ad elevationem. Adoramus te, Christe

- Paranymphus

Hans Judenkünig (also Judenkunig or Judenkönig c. 1445 – 4 March 1526) was a German lutenist, lute maker, and composer of the Renaissance.

Gilles Mureau (also Mureue, as he spelled it himself) (c. 1450 – July 1512) was a French composer and singer of the Renaissance. He was active in central France, mainly Chartres, and was one of the composers listed by Eloy d’Amerval in his long 1508 poem Le livre de la deablerie as one of the great composers of the age, resident in Paradise – even though he was still alive. While he probably wrote a substantial number of works, only four secular compositions survive.

Only four pieces by Mureau survive, all rondeaux. They are found in various sources, including Petrucci’s famous Odhecaton. They are typical of the refined French secular music of the late 15th century, with balanced phrases, careful attention to melody and clear delineation of the text; some brief portions use imitation.

Robert Wylkynson (sometimes Wilkinson) (ca. 1450 – Eton after 1515) was an English composer of the Renaissance. His works are in included in the Eton Choirbook. Wylkynson became parish clerk of Eton in 1496 then in 1500 he was promoted to Informator – the master of the choristers.

Only four works survive:

- 2x Salve Regina

- Jesus autem transiens/Credo in Deum à 13

- motet O virgo prudentissima (fragmentary)

But these works show Wylkynson to have been an extremely ambitious composer and a more than competent one.

- Salve Regina à 9

Walter Lambe (1450–1? –1504) was an English Renaissance composer. His works are well represented in the Eton Choirbook. Also the Lambeth Choirbook and the Caius Choirbook include his works.

Matthaeus Pipelare (c. 1450 – c. 1515) was a Netherlandish composer, choir director, and possibly wind instrument player of the Renaissance. Pipelare’s style was wide-ranging; he wrote in almost all of the vocal forms current in his day: masses, motets, secular songs in all the local languages. No instrumental music has survived. In mood his music ranged from light secular songs to sombre motets related to those of Pierre de La Rue, an almost exact contemporary.

He wrote 11 complete masses which have survived to modern times (although many of the manuscripts were destroyed in the Second World War), as well as 10 motets, and 8 chansons; the chansons are both in French and Dutch. One of the masses is a four-voice cantus firmus setting of L’homme armé, a style which was already old-fashioned by the time he was writing; the tune moves from voice to voice, but is usually in the tenor. His Missa Fors seulement is based on his own chanson, which he used as the cantus firmus. Memorare Mater Christi is a seven-part motet on the sorrows of the Virgin Mary; each of the seven voices represents a different dolor. The third of the seven voices even quotes the contemporary Spanish villancico Nunca fué pena mayor (never was there a greater pain) by Juan de Urrede. Sequential writing and syncopated rhythms are characteristic of his music.

- Missa “Fors Seulement” a 5: III. Credo

- Missa “Fors Seulement” a 5: IV. Sanctus

Heinrich Isaac (ca. 1450 – 26 March 1517) was a Renaissance composer of south Netherlandish origin. He wrote masses, motets, songs (in French, German and Italian), and instrumental music. A significant contemporary of Josquin des Prez, Isaac influenced the development of music in Germany. Isaac was one of the most prolific composers of the time, producing an extraordinarily diverse output, including almost all the forms and styles current at the time; only Lassus, at the end of the 16th century, had a wider overall range. His best known work may be the song “Innsbruck, ich muss dich lassen”, of which he made at least two versions. It is possible, however, that the melody itself is not by Isaac, and only the setting is original. The same melody was later used as the theme for the Lutheran hymn “O Welt, ich muss dich lassen”, which was the basis of works by Johann Sebastian Bach, including his St Matthew Passion and Johannes Brahms.

Of his settings of the ordinary of the mass, 36 survive; others are believed to have been lost. Numerous individual movements of masses survive as well. But it is composition of music for the Proper of the Mass – the portion of the liturgy which changed on different days, unlike the ordinary, which remained constant – which gave him his greatest fame. The huge cycle of motets which he wrote for the mass Proper, the Choralis Constantinus, and which he left incomplete at his death, would have supplied music for 100 separate days of the year.

Isaac is held in high regard for his Choralis Constantinus. It is a huge anthology of over 450 chant-based polyphonic motets for the Proper of the Mass. It had its origins in a commission that Isaac received from the Cathedral in Konstanz, Germany in April 1508 to set many of the Propers unique to the local liturgy. Isaac was in Konstanz because Maximilian had called a meeting of the Reichstag (German Parliament of nobles) there and Isaac was on hand to provide music for the Imperial court chapel choir. After the deaths of both Maximilian and Isaac, Ludwig Senfl, who had been Isaac’s pupil as a member of the Imperial court choir, gathered all the Isaac settings of the Proper and placed them into liturgical order for the church year. But the anthology was not published until 1555, after Senfl’s death, by which time the reforms of the Council of Trent had made many of the texts obsolete. The motets remain some of the finest examples of chant-based Renaissance polyphony in existence.

Isaac composed a 6-voice motet Angeli Archangeli for the Feast of All Saint’s Day, honoring angels, archangels, and all other saints. Another famous motet by Isaac is Optime pastor (Optime divino), written for the accession to the papacy of Medici pope Leo X. This motet compares the Pope to a shepherd capable of soothing all of his flock and binding them together.

The influence of Isaac was especially pronounced in Germany, due to the connection he maintained with the Habsburg court. He was the first significant master of the Franco-Flemish polyphonic style who both lived in German-speaking areas, and whose music was widely distributed there. It was through him that the polyphonic style of the Netherlands became widely accepted in Germany, making possible the further development of contrapuntal music there.

- Motet: Optime Divion date munere pastor ovili à 6 v.

- Lied: O Welt, ich muß dich lassen

- Virgo prudentissima

- Innsbruck, ich muss dich lassen

Josquin Lebloitte dit des Prez (c. 1450–1455 – 27 August 1521) was a composer of High Renaissance music, who is variously described as French or Franco-Flemish. Considered one of the greatest composers of the Renaissance, he was a central figure of the Franco-Flemish School and had a profound influence on the music of 16th-century Europe.

Building on the work of his predecessors Guillaume Du Fay and Johannes Ockeghem, he developed a complex style of expressive—and often imitative—movement between independent voices (polyphony) which informs much of his work. He further emphasized the relationship between text and music, and departed from the early Renaissance tendency towards lengthy melismatic lines on a single syllable, preferring to use shorter, repeated motifs between voices.

Josquin was a singer, and his compositions are mainly vocal. They include masses, motets and secular chansons (with French text). Influential both during and after his lifetime, Josquin has been described as the first Western composer to retain posthumous fame. His music was widely performed and imitated in 16th-century Europe.

- Fortuna desperata: Agnus Dei

- Missa l’homme armé sexti toni: V. Agnus Dei

- Missa Mater Patris, NJE 10.1: IV. Sanctus

- Missa Hercules Dux Ferrariae: VII. Inviolata, integra, et casta es Maria

- Inviolata, integra et casta es

- Qui habitat in adiutorio altissimi à 24

- Christus mortuus est

- Misericordias Domini

- Nymphes des bois

- Parfons regretz

- Plaine de dueil

- Proch dolor

- Regretz sans fin

- Sit nomen domini

- Recordare virgo mater: I. Prima pars (attribution uncertain)

- Recordare virgo mater: II. Secunda pars (attribution uncertain)

Franchinus Gaffurius (Franchino Gaffurio; 14 January 1451 – 25 June 1522) was an Italian music theorist and composer of the Renaissance. Gaffurius wrote masses, motets, settings of the Magnificat, and hymns, mainly during his Milan years. Some of the motets were written for ceremonial occasions for his ducal employer; many of the masses show the influence of Josquin, and all are in flowing Netherlandish polyphony, though with an admixture of Italian lightness and melody. His music was collected in four codices under his own direction.

Jean Japart (fl. c. 1474–1481) was a Franco-Flemish composer of the Renaissance, active in Italy. He was a popular composer of chansons, and may have been a friend of Josquin des Prez.

Japart was the composer of 23 chansons which are extant. A lost composition by Josquin, Revenu d’oultrements, Japart is often cited as evidence of a friendship between the two composers; if so, they probably met in Milan after 1481, since Josquin did not go to Italy until around 1484.

Stylistically, Japart’s music is influenced by Busnois, one of the earlier group of Burgundian composers. He was fond of the quodlibet, the combination of several pre-existing tunes in ingenious ways, and he also wrote puzzle canons — compositions which the singers were intended to figure out from clues given in the text. For example, one of his chansons can only be performed correctly by transposing one of the parts down a twelfth and singing it in retrograde motion. (When a puzzle canon is solved correctly, the parts fit together without violation of the prevailing rules of counterpoint, which in the 15th century are described in the works of theorists such as Tinctoris.) Japart’s music was evidently popular, since many of his chansons were reprinted by Petrucci and achieved wide distribution.

Edmund Sturton (or Stourton, fl. late 15th-early 16th century) was an English composer of the Renaissance. Little is known about his life and career, but he is believed to be the same Sturton whose six-part setting of Ave Maria ancilla Trinitatis is found in the Lambeth Choirbook. Another six-part setting, this of the Gaude virgo mater Christi, may be found in the Eton Choirbook; its voices cover a range of fifteen notes.

Robert de Févin (late 15th and early 16th centuries) was a French composer of the Renaissance. He wrote masses, motets and lamentations, though little of his work has survived. Three masses, a four-voice credo from a mass (the rest of which has been lost), two settings of the Lamentations of Jeremiah, one five-voice Marian antiphon (Alma Redemptoris mater), and the music of a six-voice motet (with the text absent) are all that survives of his work. Stylistically it is similar enough to his brother Antoine’s music that several of Robert’s pieces have been misattributed to Antoine. Robert evidently emulated the style of Josquin, copying not only the smooth polyphony of the more famous composer but basing two of his masses directly on works by him. Some of Févin’s music can be found in the Medici Codex of 1518.

Pierre de la Rue (c. 1452 – 20 November 1518) was a Franco-Flemish composer and singer of the Renaissance. His name also appears as Piersson or variants of Pierchon and his toponymic, when present, as various forms of de Platea, de Robore, or de Vico. A member of the same generation as Josquin des Prez, and a long associate of the Habsburg-Burgundian musical chapel, he ranks with Agricola, Brumel, Compère, Isaac, Obrecht and Weerbeke as one of the most famous and influential composers in the Netherlands polyphonic style in the decades around 1500.

La Rue wrote masses, motets, Magnificats, settings of the Lamentations, and chansons, a diverse range of compositions reflective of his status as the primary composer at one of Europe’s most renowned musical institutions, surrounded by other similarly creative people. Some scholars have suggested that he composed music only during the last 20 years of his life, mainly when he was in the imperial service; but it has proven difficult to date any of his works precisely, although it has been possible to suggest groupings based on a rough chronology. Stylistically, his works are more similar to those of Josquin than to those of any other composer working at the same time. In fact, misattribution of doubtful works has gone both ways.

Yet there are some unique features of La Rue’s style. He had a liking for extreme low voice ranges, descending sometimes to C or even the subterranean B flat below the bass staff; he employed more chromaticism than most of his contemporaries; and much of his work is rich in dissonance. He also broke up long, dense textures by inserting contrasting passages for two voices only, something done also by Ockeghem and Josquin. He was one of the first routinely to expand vocal forces from the standard four, to five or six. One of his masses for six voices, the Missa Ave sanctissima Maria, is a six-voice canon, a technically difficult feat reminiscent of some of the work of Ockeghem. This is also the earliest six-voice mass known to exist.

Canonic writing is a particularly important feature of La Rue’s style, for which he has been particularly celebrated. He liked to write canons of considerable complexity, rather than restrict himself to simple imitation. The second of his two masses based on the L’homme armé tune begins and ends with mensuration canons, canons in which all the voices sing the same material, but at different tempi; this is yet another feat of contrapuntal virtuosity worthy of Josquin or Ockeghem; indeed La Rue sometimes seemed to be in conscious competition with the more renowned Josquin. The closing Agnus Dei of this mass is the only known mensuration canon of the entire era for four voices, with all four voices singing the same tune. La Rue wrote six pieces that are completely canonic from start to finish, including two masses, three motets and a chanson; he wrote three more masses, two motets, and three chansons which are based on canon but contain some free sections; numerous other works include canonic sections. In his use of canons, he may have been influenced by Matthaeus Pipelare, who wrote an early canonic mass La Rue almost certainly knew, since it was part of the repertory of the Habsburg court chapel.

La Rue was one of the first to use the parody technique thoroughly, permeating the texture of a mass with music drawn from all voices of a pre-existing source. Some of his masses use cantus firmus technique, but rarely strictly; he often preferred the paraphrase technique, in which the monophonic source material is embellished and migrates between voices.

La Rue wrote one of the earliest polyphonic Requiem Masses to survive, and it is one of his most famous works. Unlike later Requiems, it includes polyphonic settings of only the Introit, Kyrie, Tract, Offertory, Sanctus, Agnus, and Communion – the Dies Iræ, often the center of gravity in more recent Requiems, was a later addition. This was the normal liturgical practice in Gallican France and the region of northern Europe in which he worked. This mass, more than many others, emphasises the low registers of voices, and even the lowest voices themselves.

Twenty-five motets by La Rue survive, being mostly for four voices. While they use imitation, the technique is more likely to occur within sections and phrases rather than at their openings, unlike in the style of Josquin. Another stylistic feature characteristic of La Rue’s motets is the use of ostinatos, which may be a single note, an interval, or a series of notes. In addition he uses germinal motifs – small easily recognizable patterns from which larger melodic units are derived, and which give unity to a composition. Overall the motets are complex contrapuntally, with the individual lines having a distinctive character, in the manner of Ockeghem. This is most true in the early works which were likely influenced by the older composer.

More than half of the motets are on the subject of the Virgin Mary. La Rue was the first composer to write a Magnificat on each of the eight tones, and additionally wrote six separate settings of the Marian antiphon Salve regina. Most likely these are early works.

His thirty chansons show a diversity of style, some being akin to the late Burgundian style (for example, as seen in the works of Hayne van Ghizeghem or Gilles Binchois), and of others using a more current imitative polyphonic style. Since La Rue never spent time in Italy, he did not employ the Italian frottola style which featured light, homophonic textures (which Josquin used so effectively in his popular El Grillo and Scaramella), and which so charmed the other members of his generation.

John Browne (1453–c. 1500) was an English composer of the Tudor period, who has been called “the greatest English composer of the period between Dunstaple and Taverner”. Despite the high level of skill displayed in Browne’s compositions, few of his works survive; Browne’s extant music is found in the Eton Choirbook, in which he is the best-represented contributor, and the Fayrfax Manuscript. His choral music is distinguished by innovative scoring, false relations, and unusually long melodic lines, and has been called by early music scholar Peter Phillips “subtle, almost mystical” and “extreme in ways which apparently have no parallel, either in England or abroad.”

All of Browne’s surviving works are found in the earlier folios of the Eton Choirbook, dating from between 1490 and 1500. According to the index of the Choirbook, ten more Browne compositions were originally included; five of these compositions have been lost, while two survive in fragmentary form. The first setting of the Salve regina, and the six part Stabat mater are perhaps best known today. His O Maria salvatoris – unusual at the time of composition in that it is set in eight-part polyphony – was highly regarded during his lifetime, and was placed at the front of the Eton Choirbook.

Browne’s music is notable for its varied and unusual vocal instrumentation; each of his surviving works calls for a unique array of voices, with no two compositions sharing a given ensemble scoring. A prime example of Browne’s penchant for unorthodox groupings is his six-voice antiphon Stabat iuxta, scored for a choir of four tenors and two basses. His choral music often displays careful treatment of the dramatic possibilities of the text and expressive use of imitation and dissonance; the aforementioned Stabat iuxta, in particular, has been noted for its “dense, almost cluster chords” and “harsh” false relations.

Other works have a wide range, with lower voices against soaring soprano lines. Though comparatively few in number compared with his continental contemporaries, Browne’s works are expressively intense and often lengthy, several lasting a quarter of an hour or so to perform. Many of the composers in the Eton Choirbook are represented only in this manuscript, due to the dissolution of the monasteries and widespread destruction of untold numbers of Catholic music manuscripts in Henry VIII’s reign. We may never know the actual output of Browne and his English contemporaries and subsequent English composers of the early 16th century.

Jacobus Barbireau (also Jacques or Jacob; also Barbirianus) (1455 – 7 August 1491) was a Franco-Flemish Renaissance composer from Antwerp. He was considered to be a superlative composer both by his contemporaries and by modern scholars; however, his surviving output is small, and he died young.

The library of the cathedral in Antwerp was destroyed by religious fanatics in 1556, including probably most of Barbireau’s music. Some, however, has survived, in sources such as the Chigi Codex. What has survived is of outstanding quality. “Barbireau shows a degree of contrapuntal polish and melodic-harmonic resourcefulness that puts him firmly on a par with such composers as Isaac and Obrecht.”

Two masses have survived as well as a Kyrie for the Easter season, and a motet on texts from the Song of Songs, Osculetur me, for four voices. The mass for five voices, Missa virgo parens Christi, is a cantus firmus mass and has an unusual arrangement where the voices have divisi parts, indicating that at least ten actual voices would be required to sing it. In this composition the textural contrasts are high, with striking homophonic passages alternating dynamically with polyphonic, and with fast-moving parts weaving around the slower-moving parts. Also featured in this mass are alternating duos (bicinia) in a call-response fashion. The motet Osculetur me uses low voice tessituras reminiscent of Ockeghem.

Of his secular music, the song Een vroylic wesen, for three voices, became a ‘hit’ song all over Europe, appearing in numerous arrangements from places as far apart as Spain, Italy and England; Heinrich Isaac used it as the basis for his own Missa Frölich wesen. Three of his surviving secular songs were used as the basis for masses, both by Isaac and Jacob Obrecht.

Robert Hacomblen (also spelt Hacomplaynt, Hacumplaynt, Hacomplayne, Hacomblene, Hacumblen) (1455 or 1456, London – 1528, Cambridge), was provost of King’s College, Cambridge. Hacomblen was a man of learning of the standard of his day, and of some accomplishments, being the probable author of a musical setting of Salve Regina for Eton Chapel, c. 1500 preserved in the Eton Choirbook and there attributed to Hacomplaynt.

Johannes Ghiselin (Verbonnet) (c. 1455–1511) was a Flemish composer of the Renaissance, active in France, Italy and in the Low Countries. He was a contemporary of Josquin des Prez, and a significant composer of masses, motets, and secular music. His reputation was considerable, as shown by music printer Ottaviano Petrucci’s decision to print a complete book of his masses immediately after his similar publication of masses by Josquin – only the second such publication in music history.

As with Josquin, Ghiselin was interested in solutions to the musical problems posed by the multiple-movement setting of the mass. Ghiselin’s masses were well-known and respected, as is made clear by Petrucci choosing to publish an entire book of them, only the second book he published devoted to masses by a single composer (1503). Most of his masses are based on chansons, including works by Antoine Busnois, Alexander Agricola, Guillaume Dufay, Loyset Compère, and himself.

Ghiselin also wrote motets, chansons, secular songs in Dutch, as well as some instrumental music. His setting of “La Spagna” for four parts is probably one of the earliest settings of this famous bassadanza tune for multiple parts, although its date has not been determined.

Arnolt Schlick (July 18?, c. 1455–1460 – after 1521) was a German organist, lutenist and composer of the Renaissance. He is grouped among the composers known as the Colorists. He was most probably born in Heidelberg and by 1482 established himself as court organist for the Electorate of the Palatinate. Highly regarded by his superiors and colleagues alike, Schlick played at important historical events, such as the election of Maximilian I as King of the Romans, and was widely sought after as organ consultant throughout his career. The last known references to him are from 1521; the circumstances of his death are unknown.

Schlick was blind for much of his life, possibly from birth. However, that did not stop him from publishing his work. He is best known for Spiegel der Orgelmacher und Organisten (1511), the first German treatise on building and playing organs. This work, highly influential during the 16th century, was republished in 1869 and is regarded today as one of the most important books of its kind. Schlick’s surviving compositions include Tabulaturen etlicher lobgesang (1512), a collection of organ and lute music, and a few pieces in manuscript. The lute pieces—mostly settings of popular songs—are among the earliest published; but Schlick’s organ music is even more historically important. It features sophisticated cantus firmus techniques, multiple truly independent lines (up to five—and, in one case, ten—voices), and extensive use of imitation. Thus, it predates the advances of Baroque music by about a hundred years, making Schlick one of the most important composers in the history of keyboard music.

Schlick’s organ music survives in two sources: the printed collection Tabulaturen etlicher lobgesang (1512) and the letter Schlick sent to Bernardo Clesio around 1520-1521. Tabulaturen contains ten compositions for organ: a setting of Salve Regina (five verses), Pete quid vis, Hoe losteleck, Benedictus, Primi toni, Maria zart, Christe, and three settings of Da pacem. Of these, only Salve Regina and the Da pacem settings are fully authentic. Much of the other music is stylistically indistinguishable from contemporary vocal works by other composers; consequently, some of the pieces may be intabulations of other composers’ works. However, as of 2009, no models are known for any of the pieces, and so Schlick’s authorship remains undisputed.

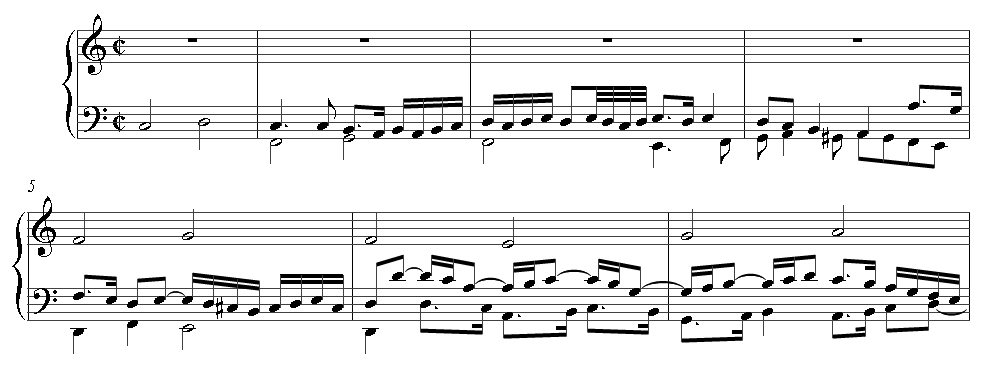

The Salve Regina setting is among the most important of Schlick’s works. Unlike most preceding and contemporary organ composers, Schlick tends to use four voices rather than three, and in the first verse there are instances of two voices in the pedal, a technique unheard of at the time. Schlick’s setting also sets itself apart by relying heavily on imitation, sequence and fragmentation of motives, techniques seldom employed so consistently in organ music of the day. The first movement begins with an imitative exposition of an original theme with an unusually wide (for a theme used imitatively) range of a twelfth and proceeds to free counterpoint with instances of fragments of the original theme. Movements 2 and 3 (Ad te clamamus and Eya ergo) begin by treating the cantus firmus imitatively, and the opening of Eya ergo constitutes one of the earliest examples of fore-imitation:

This technique, in which a motif treated imitatively “foreshadows” the entrance of the cantus firmus, later played a major part in the development of the organ chorale. Schlick’s methods of creating complementary motives also look towards a much later stage of evolution, namely the techniques employed by Jan Pieterszoon Sweelinck. Early music scholar Willi Apel, who authored the earliest comprehensive analysis of Schlick’s keyboard music, writes:

Schlick’s Salve is one of the truly great masterpieces of organ art, perhaps the first one to deserve to be so ranked. It still breathes the strict spirit of the Middle Ages, which brought forth so many wonderful works, but new forces are already at work that lend this composition a novel fulness of expression and sound.

Schlick’s three Da pacem settings also look to the future, because, although Schlick does not refer to them as a cycle anywhere in the Tabulaturen, the placement of the cantus firmus suggests that the three settings are part of a large plan. The antiphon is in the discantus in the first setting, in the tenor in the second, and in the bass in the third. Similar plans are observed in Sweelinck’s and later composers’ chorale variations. Technically, Schlick’s settings exhibit a contrapuntal technique similar to that of Salve Regina.

Schlick’s Benedictus and Christe are three-voice settings of mass movements. The former has been called “the first organ ricercar” because of its use of imitation in a truly fugal manner, but it remains unclear whether the composition is an original piece by Schlick or an intabulation of a vocal work by another composer. The piece is in three sections, the first of which begins with a fugal exposition, and the second is a canon between the outer voices. Schlick’s Christe is more loosely constructed: although imitation is used throughout, there are no fugal expositions or canonic techniques employed. The piece begins with a long two-voice section. Other organ pieces in the Tabulaturen employ a variety of methods, most relying on imitation (with the notable exception of Primi toni, which is also unusual for its title, which merely indicates the tone, but not the cantus firmus). For example, Schlick’s setting of Maria zart (a German song famously used by Jacob Obrecht for Missa Maria zart, one of the longest polyphonic settings of the Mass Ordinary ever written) splits the melody into thirteen fragments, treated imitatively one by one. A similar procedure, only with longer fragments of the melody used, is employed in Hoe losteleck, a piece based on a song which may have had secular character. Pete quid vis, a piece of unknown origins and function, consists of a large variety of different treatments of a single theme, either treated imitatively itself, or accompanied by independently conceived imitative passages.

Schlick’s letter to Bernardo Clesio contains his only known late works: a set of eight settings of the sequence verse Gaude Dei genitrix (from the Christmas sequence Natus ante saecula) and a set of two settings of the Ascension antiphon Ascendo ad Patrem meum. Both sets have didactic purposes. Gaude Dei genitrix settings establish various ways of reinforcing a two-voice setting, in which the chant is accompanied by moderately ornamented counterpoint, by duplicating both lines in parallel thirds, fourths, or sixths. The pieces, which may have been intended for voices rather than the organ, range from three- to five-voice settings. Schlick himself noted the didactic aspect, writing that he “found and made a separate rule for each setting, which are so clear that it will be easy to set all chants in the same manner.” His Ascendo ad Patrem meum settings serve a different purpose, but also are a miniature encyclopaedia: the first setting is in two voices (and so the most basic of all possible settings), whereas the second is in ten voices (and so the most advanced of all possible settings). The ten-voice work is unique in organ repertoire, both for the polyphonic scope and the pedal technique.

Lute Settings

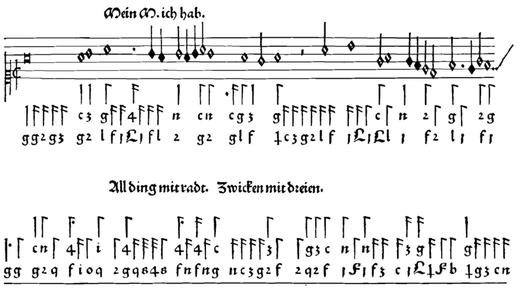

The Tabulaturen etlicher lobgesang is the earliest extensive source of German lute music and also one of the earliest published collections of lute music known. There are fifteen lute pieces, twelve of which are duets for voice and lute. The pieces are organized by difficulty, which reflects the didactic aspect of the Tabulaturen. Curiously, Schlick does not include performing instructions, which are commonplace in most later German publications, and furthermore, no texts are included, although most can be found in contemporary sources—there are just three songs unique to the Tabulaturen (Mein lieb ist weg, Philips zwolffpot and All Ding mit radt).

Almost all the songs are settings of German polyphonic Lieder on secular texts. There are two exceptions. The first, Metzkin Isaack, may be of Netherlandish origin, and there is a possibility that Schlick learned the piece from Petrucci’s Harmonice Musices Odhecaton. This would imply that Schlick borrowed the idea to apply for an imperial privilege for Spiegel and Tabulaturen from Petrucci. The second exception is All Ding mit radt, which is different from every other piece in the Tabulaturen: it relies not on the phrase structure of the song, like other settings, but rather on motivic and harmonic principles. Also, unlike other lute settings, it does not use bar form.

In most settings Schlick uses mixed notation: the upper part is notated mensurally, while the lower parts are given in tablature. The practice was rarely used in Germany at the time, but it appears in many contemporary French and Italian sources, such as collections of frottolas by Franciscus Bossinensis (1509–1511) or Marchetto Cara (c. 1520), and Pierre Attaingnant’s publications (late 1520s). Another important deviation from the German norm is Schlick’s tendency to put the cantus firmus in the highest part, the discantus, whereas the norm for German Lieder was cantus firmus in the tenor.

As is usual for lute intabulations, none of Schlick’s settings are completely faithful to their models. The changes range from addition of modest ornaments, as in Nach lust or Vil hinderlist, to insertions of new material, as in Mein M. ich hab and Weg wart dein art. One particularly important change occurs in Schlick’s intabulation of Hertzliebstels pild, in which Schlick attempts a type of word painting: the words “mit reichem Schall” (“with rich sound/splendor”) are illustrated by an increase in rhythmic activity. The three solo lute settings are all in three voices, and present three distinct ways of three-voice intabulation. All Ding mit radt contains numerous passages in two voices, and so serves as an introduction to playing three-voice music. Wer gnad durch klaff is one of Schlick’s most straightforward intabulations, using most of the original material unchanged. Finally, Weg wart dein art is a free intabulation, with numerous ornaments, figuration and other embellishments. The vast majority of Schlick’s lute pieces are not exceptionally virtuosic, and are somewhat easier to perform than near-contemporary lute music by Hans Neusidler and Hans Judenkünig; however, the works in the Tabulaturen cannot be used as a basis to judge Schlick’s technique, since the book had a didactic aspect, and Schlick planned a second volume with more complex and difficult music.

Schlick was of the utmost importance in the early history of organ music in Germany. He was a much sought-after organ consultant, and while his blindness prevented him from doing much of the construction he was closely associated with organ-builders as an advisor; he tested new organs, performed widely, and was a strong influence among other composers at the time. His method of weaving contrapuntal lines around a cantus firmus, derived from a chorale tune, can be seen as foreshadowing the development of the chorale prelude in a later age. Schlick can be seen as the first figure in a long line of development which culminated in the music of J.S. Bach more than two hundred years later.

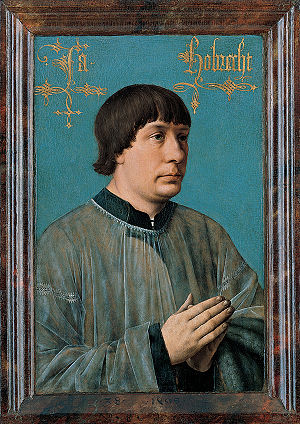

Jacob Obrecht (1457/8 – late July 1505) was a Flemish composer of masses, motets and songs. He was the most famous composer of masses in Europe of the late 15th century and was only eclipsed after his death by Josquin des Prez. Combining modern and archaic elements, Obrecht’s style is multi-dimensional. Perhaps more than those of the mature Josquin, the masses of Obrecht display a profound debt to the music of Johannes Ockeghem in the wide-arching melodies and long musical phrases that typify the latter’s music. Obrecht’s style is an example of the contrapuntal extravagance of the late 15th century. He often used a cantus firmus technique for his masses: sometimes he divided his source material up into short phrases; at other times he used retrograde versions of complete melodies or melodic fragments. He once even extracted the component notes and ordered them by note value, long to short, constructing new melodic material from the reordered sequences of notes. Clearly to Obrecht there could not be too much variety, particularly during the musically exploratory period of his early twenties. He began to break free from conformity to formes fixes, especially in his chansons. Of the formes fixes, the rondeau retained its popularity longest. However, he much preferred composing Masses, where he found greater freedom. Furthermore, his motets reveal a wide variety of moods and techniques.

Despite working at the same period, Obrecht and Ockeghem (Obrecht’s senior by some 30 years) differ significantly in musical style. Obrecht does not share Ockeghem’s fanciful treatment of the cantus firmus but chooses to quote it verbatim. Whereas the phrases in Ockeghem’s music are ambiguously defined, those of Obrecht’s music can easily be distinguished, though both composers favor wide-arching melodic structure. Furthermore, Obrecht splices the cantus firmus melody with the intent of audibly reorganizing the motives; Ockeghem, on the other hand, does this far less.

Obrecht’s procedures contrast sharply with the works of the next generation, who favored an increasing simplicity of approach (prefigured by some works of his contemporary Josquin). Although he was renowned in his time, Obrecht appears to have had little influence on subsequent composers; most probably, he simply went out of fashion along with the other contrapuntal masters of his generation.

- Missa Pfauenschwanz: Et resurrexit

Jean Mouton (c. 1459 – 30 October 1522) was a French composer of the Renaissance. He was famous both for his motets, which are among the most refined of the time, and for being the teacher of Adrian Willaert, one of the founders of the Venetian School.

Mouton was hugely influential both as a composer and as a teacher. Of his music, 9 Magnificat settings, 15 masses, 20 chansons, and over 100 motets survive; since he was a court composer for a king, the survival rate of his music is relatively high for the period, it being widely distributed, copied, and archived. In addition, the famous publisher Ottaviano Petrucci printed an entire volume of Mouton’s masses (early in the history of music printing, most publications contained works by multiple composers). His work was also published by Pierre Attaingnant.

The style of Mouton’s music has superficial similarities to that of Josquin des Prez, using paired imitation, canonic techniques, and equal-voiced polyphonic writing: yet Mouton tends to write rhythmically and texturally uniform music compared to Josquin, with all the voices singing, and with relatively little textural contrast. Glarean characterized Mouton’s melodic style with the phrase “his melody flows in a supple thread.”

Around 1500, Mouton seems to have become more aware of chords and harmonic feeling, probably due to his encounter with Italian music. At any rate this was a period of transition between purely linear thinking in music, in which chords were incidental occurrences as a result of correct usage of intervals, and music in which the harmonic element was foremost (for example in lighter Italian forms such as the frottola, which are homophonic in texture and sometimes have frankly diatonic harmony).

Mouton was a fine musical craftsman throughout his life, highly regarded by his contemporaries and much in demand by his royal patrons. His music was reprinted and continued to attract other composers even later in the 16th century, especially two joyful Christmas motets he wrote, Noe, noe psallite noe, and Quaeramus cum pastoribus, which several later composers used as the basis for masses.

He also influenced posthumously the outstanding music theorist Gioseffo Zarlino, himself a pupil of Willaert, who referred to him, somewhat enthusiastically as his “precettore”.

Paul Hofhaimer (25 January 1459 – 1537) was an Austrian organist and composer. He was particularly gifted at improvisation, and was regarded as the finest organist of his age by many writers, including Vadian and Paracelsus; in addition he was one of only two German-speaking composers of the time (Heinrich Isaac was the other) who had a reputation in Europe outside of German-speaking countries. He is grouped among the composers known as the Colorists.

Hofhaimer was a spectacularly gifted improviser, and witnesses attested to his unequaled gift; he could play for hours, never repeating himself: “one would wonder not so much how the ocean gets all the water with which to feed the rivers, but how this man gets the ideas for all his melodies.” Not only was he a performing musician, though, he was the teacher of an entire generation of German organists: and the famous school of German organists of the Baroque era can trace much of its lineage to Hofhaimer. In addition, some of the organists he trained went on to Italy, for example Dionisio Memno, who became organist at St. Mark’s in Venice, and there passed on technique learned from Hofhaimer to the organists who were part of the early Venetian school.

While he was most prolific as a composer for organ, little of that music has survived in its original form. Most of the surviving works are either lieder in three or four voices, or arrangements (intabulations) of them for either keyboard or lute. The large quantity of surviving copies of his songs from different locations in Europe, usually in arrangements, attests to their popularity. The handful of pieces for organ which have survived show Hofhaimer’s gift for composing polyphonic lines around a cantus firmus.

His German lieder are typical of the time, and usually in bar form, with one section being polyphonic and the other being more chordal. He rarely used the smooth polyphonic texture then being cultivated by the Franco-Flemish composers such as Josquin or Gombert, a style he probably first encountered in Innsbruck with the music of Isaac. Hofhaimer was also well known as an organ consultant, and frequently advised on the building and maintenance of organs.

Marbrianus de Orto (Dujardin; also Marbriano, Marbrianus; c. 1460 – January or February 1529) was a Dutch composer of the Renaissance (Franco-Flemish school). He was a contemporary, close associate, and possible friend of Josquin des Prez, and was one of the first composers to write a completely canonic setting of the Ordinary of the Mass.

Marbrianus de Orto was a moderately prolific composer of masses, motets, lamentations, and chansons, many of which have survived. He was famous enough that Ottaviano Petrucci published a book of his masses in 1505—one of his earliest publications, and one of the earliest collections of printed music. De Orto’s book of masses followed after those by Josquin, Jacob Obrecht, Antoine Brumel, Johannes Ghiselin, Pierre de La Rue, and Alexander Agricola.

Petrucci published five of de Orto’s masses in this collection. All are cantus firmus masses, and include a Missa L’homme armé, based on the famous tune, probably composed in the early to mid 1480s.

Among his masses is the unusual Missa [Ad fugam], one of only a handful of freely composed canonic masses from the period, including Johannes Ockeghem’s Missa prolationum, based entirely on mensuration canons. De Orto’s Missa [Ad fugam] may be related another canonic mass in a Vatican manuscript, later named “Missa ad fugam” and attributed to Josquin by Petrucci. Both masses use strict canon at the fifth between superius and tenor, as well as a head motive in most movements. The same title was used to describe the canonic “Missa Sine nomine” in a later print by Antico.

De Orto’s motets also usually use cantus firmus technique. The Salve regis mater sanctissima, though anonymous in its only surviving source, is probably by de Orto and was composed for the accession of Alexander VI in 1492.

Some of the chansons are akin to the typical French style of the early 16th century—quick, light, and imitative; others are more in line with the Burgundian style of the formes fixes. De Orto also wrote an early setting of Dido’s lament, Dulces exuviae, from the Aeneid (iv.651–4), containing extensive chromatic writing.

Johannes Prioris (c. 1460 – c. 1514) was a Netherlandish composer of the Renaissance. He was one of the first composers to write a polyphonic setting of the Requiem Mass. Prioris wrote six masses, of which five are still extant, including a famous Requiem, which he may have written for the funeral of Anne of Brittany, who died in 1514. He also wrote settings of the Magnificat, motets, chansons, and some examples of an early 16th-century genre which blended the last two: the motet-chanson. Most of his chansons look back to the style of Antoine Busnois and Hayne van Ghizeghem, while his motet writing, and especially his mass writing, shows elements of Italian influence, such as a chordal rather than a densely contrapuntal style.

Antoine Brumel (c. 1460 – 1512 or 1513) was one of the first renowned French members of the Franco-Flemish school of the Renaissance, and, after Josquin des Prez, was one of the most influential composers of his generation. Brumel was at the center of the changes that were taking place in European music around 1500, in which the previous style of highly differentiated voice parts, composed one after another, was giving way to smoothly flowing, equal parts, composed simultaneously. These changes can be seen in his music, with some of his earlier work conforming to the older style, and his later compositions showing the polyphonic fluidity which became the stylistic norm of the Josquin generation. Brumel is best known for his masses, the most famous of which is the twelve-voice Missa Et ecce terræ motus. Techniques of composition varied throughout his life: he sometimes used the cantus firmus technique, already archaic by the end of the 15th century, and also the paraphrase technique, in which the source material appears elaborated, and in other voices than the tenor, often in imitation. He used paired imitation, like Josquin, but often in a freer manner than the more famous composer. A relatively unusual technique he used in an untitled mass was to use different source material for each of the sections (mass titles are taken from the pre-existing composition used as their basis: usually a plainchant, motet or chanson: hence the mass is without title). Brumel wrote a Missa l’homme armé, as did so many other composers of the Renaissance: appropriately, he set it as a cantus firmus mass, with the popular song in long notes in the tenor, to make it easier to hear. All of his masses, with the exception of the highly unusual twelve-voice Missa Et ecce terræ motus, are for four voices.

- Missa “Et ecce terrai motus” Kyrie Eleison

- Missa “Et ecce terrai motus” Christe Eleison

- Nato canunt omnia

Francisco de la Torre (c. 1460 – c. 1504) was a Spanish composer mainly active in the Kingdom of Naples. His hometown may have been Seville. His music can be found in La música en la corte de los Reyes Musulmanes, edited by H. Anglès (1947–51).

His surviving compositions include one courtly instrumental dance, a funeral responsory (Ne recorderis), an office of the dead, and ten villancicos (three sacred, seven secular). According to Robert Stevenson, his “funerary works, notably the motet Libera me, are of great beauty and expressiveness.” Four of his secular villancicos may be classified as romances, having something in common with the Netherlandish composer Juan de Urrede active in Spain in the previous generation. One, Pascua d’Espíritu Sancto, was composed for the feast of Corpus Christi the day after the reconquista of Ronda on 1 June 1485. It is based on a portion of the verse account of the Granada War by Hernando de Ribera.

Ten of his compositions are included in the Palace Songbook collection. Including, notably, an instrumental dance Alta danza that uses the famous tenor La Spagna, whose choreography in other contexts is known.

Juan de Anchieta (1462 – 1523) was a leading Spanish Basque composer of the Renaissance, at the Royal Court Chaplaincy in Granada of Queen Isabel I of Castile. Some thirty of Juan de Anchieta’s compositions survive, among them two complete Masses, two Magnificats, a Salve Regina, four attributed Passion settings, with other sacred works and four compositions with Spanish texts. The two Masses and many motets which survived, show extensive use of plainsong and much chordal writing. He was among the leading Spanish composers of his generation, writing music for the ample resources of the court chapel of the Catholic Monarchs. Anchieta might be the author of the motet Epitaphion Alexandri Agricolae symphonistae regis Castiliae (published in 1538), which contains important details of the Agricola’s biography.

Robert Fayrfax (23 April 1464 – 24 October 1521) was an English Renaissance composer, considered the most prominent and influential of the reigns of Kings Henry VII and; Henry VIII of England. His surviving works are six masses, two Magnificats, thirteen motets, nine part songs and two instrumental pieces. His masses include the ‘exercise’ for his doctorate, the mass O quam glorifica. One of his masses, Regali ex progenie, was copied at King’s College, Cambridge and three other pieces (Salve regina, Regali Magnificat, and the incomplete Ave lumen gratiae) are in the Eton Choirbook. One of his masses, O bone Jesu, commissioned by Lady Margaret Beaufort, is considered the first Parody mass. He has been described as the leading figure in the musical establishment of his day and the most admired composer of his generation. His work was a major influence on later composers, including John Taverner (1490–1545) and Thomas Tallis (1505–85).

William Cornysh (1465 – October 1523) (also spelled Cornyshe or Cornish) (1465 – October 1523) was an English composer, dramatist, actor, and poet.

The Eton Choirbook (compiled c. 1490–1502) contains several works by Cornysh: Salve Regina (found in several other sources as well), Stabat mater, Ave Maria mater Dei, Gaude virgo mater Christi, and a lost Gaude flore virginali. The Caius Choirbook (c. 1518–1520) contains a Magnificat. Other sources refer to lost works: three Masses, another Stabat mater, another Magnificat, Altissimi potentia, and Ad te purissima virgo. He also produced secular vocal music and the notable English sacred anthem Woefully arrayed. There is also an extended and somewhat erudite three-part instrumental work based on steps of the hexachord and its mutations, Fa la sol, and another untitled piece. These secular works are found in the so-called Fayrfax Book (copied in 1501).

If all the earlier sacred music is by the same Cornysh (junior) as the secular music then he was a composer of some breadth, although not without parallel. The works by “Browne” in the Fayrfax Book display a similar difference in style to those by the John Browne of the Eton Choirbook, but are probably the same composer nonetheless. The occurrence of Cornysh’s Magnificat (in the same style as the Eton works) falls nearly two decades after the death of the older Cornysh, and thus is far more likely the work of the younger Cornysh, by then by far one of the country’s most important musicians. Furthermore, the works by Cornysh in the Eton Choirbook seem to be amongst the most “modern” in that collection. While they do not pursue the simplifying approach of Fayrfax (an almost exact contemporary of Cornysh junior, and fellow at Court and Chapel), and remain in a more old-fashioned florid melodic style, they adopt proto-madrigalian manners (for example in the setting of words like “clamorosa”, “crucifige” and “debellandum” in the Stabat mater) and have a particularly developed sense of tonal movement (for example, in the Stabat mater, the closing “Amen” features deliberate use of F sharps as leading notes to give a sense of tonal cadence into G, or employing E flats at “Sathanam” to give a tonal cadence onto B flat, emphasizing the “strong” nature of the text at that moment, employing the bass-movement V-I), as well as adopting a more modern sense of the expressive appoggiatura in melodic shapes and in bringing out the stresses of the Latin by such devices (for example, again the Stabat mater, the use of appoggiaturas in the Bassus part to express “ContriSTANtem et doLENtem” in the first few measures, and again at “Contemplari doLENtem cum filio?”), and the use of purely rhetorical gestures (such as the exclamation “O” by full choir in the middle of the soloists’ section starting the Stabat mater). It is not impossible to see in these mannerisms the work of a great dramatist.

The works of John Browne are given pride of place in the Eton manuscript. It seems that in the examples given above that Cornysh may have been emulating Browne (his own Stabat mater features a celebrated madrigalian setting of “crucifige”, and his O Maria salvatoris Mater features the exclamation “En” (=”Oh”) in a similar way to Cornysh’s interjection in his Stabat mater).

Thus it seems that the Eton Cornysh was writing after Browne, and this would place his work amongst the later ones of the Eton Choirbook: additionally the approaches do not seem to be those of an older man, being much more suggestive of a young and original composer. The traditional ascription of all the works to Cornysh junior is the one more generally accepted. However, the possibility that the Eton works are the works of a generation earlier remains, and has interesting implications if true.

The musicologist David Skinner, in the booklet to The Cardinall’s Musick’s CD Latin Church Music, puts forward the proposition that the pre-Reformation Latin church music (including the works in the Eton manuscript) was composed by the father, whilst the son is the composer of the pieces in English and the courtly songs.

Sebastian Virdung (born c. 1465) was a German composer and theorist on musical instruments. He is grouped among the composers known as the Colorists. In 1511, he published his treatise Musica getuscht und ausgezogen. The text is described as the first printed book on the subject. It covered the theory of music, counterpoint and composition. However, none of these subjects are to be found in the printed work that survives. Existing sections are based on instruments with illustrations and is notable for being the oldest printed source on this subject. The second is said to be Musica instrumentalis deudsch (1529) by Martin Agricola. These works are both illustrated, and important for the history of European instruments. It classifies instruments into families. It is also a source on musical notation.

Pedro de Escobar (c. 1465 – after 1535), a.k.a. Pedro do Porto, was a Portuguese composer of the Renaissance, mostly active in Spain. He was one of the earliest and most skilled composers of polyphony in the Iberian Peninsula, whose music has survived. Two complete masses of Escobar have survived, including a Requiem setting (Missa pro defunctis), the earliest by a composer from the Iberian Peninsula. His known work also includes a setting of the Magnificat, 7 motets (including one Stabat Mater), 4 antiphons, 8 hymns, and 18 villancicos, but it is highly probable that his authorship is hidden among the many anonymous works of the Portuguese and Spanish Renaissance manuscripts. His music was popular, as attested by the appearance of copies in far-off places; for example native scribes copied two of his manuscripts in Guatemala. His motet Clamabat autem mulier Cananea was particularly praised by his contemporaries, and served as the source for instrumental pieces by later composers, namely Alonso Mudarra.

Richard Davy (c. 1465–1507) was an Englsih Renaissance composer, organist and choirmaster, one of the most represented in the Eton Choirbook. Davy is the second most represented composer in the Eton choirbook, with nine compositions including his most celebrated work, the Passio Domini in ramis palmarum or Passion according to St Matthew. His work is considered more florid than that of his contemporaries Robert Fayrfax and William Cornish and may have had considerable impact on later figures such as John Taverner.

Marchetto Cara (c. 1465 – probably 1525) was an Italian composer, lutenist and singer of the Renaissance. He was mainly active in Mantua, was well-connected with the Gonzaga and Medici families, and along with Bartolomeo Tromboncino, was well known as a composer of frottolas.

Though predominantly a composer of frottolas, a light secular form and ancestor of the madrigal, he also wrote a few sacred pieces, including a three-voice Salve Regina (one of the Marian Antiphons) as well as seven laude spirituali. His frottolas are for the most part homophonic, with short passages of imitation only at the beginnings of phrases; they are catchy, singable, and often use dance-like rhythms. The poetry for most of his 100 frottolas is anonymous, though the authors of 16 poems have been identified. Most of the poems are in the form of the barzellette, but there are also strambotti, sonnets, capitoli and ode. Almost everything is in a verse-refrain format. One of Cara’s best known frottolas, Io non compro più speranza was composed in 1504 and published in the first book of Frottolas of Petrucci.

Some of his later frottolas are more serious in character, and foreshadow the development of the madrigal, which took place in the late 1520s and 1530s, right after his death.

Giacomo Fogliano (da Modena; also Jacopo, Fogliani; 1468 – 10 April 1548) was an Italian composer, organist, harpsichordist, and music teacher of the Renaissance, active mainly in Modena in northern Italy. He was a composer of frottole, the popular vocal form ancestral to the madrigal, and later in his career he also wrote madrigals themselves. He also wrote some sacred music and a few instrumental compositions.

Of his music, three motets, two laude, 13 frottolas (one of which is attributed in one source to Bartolomeo Tromboncino), 29 madrigals, and four keyboard ricercars have survived. That one of the frottolas was published by Petrucci only one year after the invention of music printing shows the esteem in which it was held, at least by that Venetian printer; Alfred Einstein, writing in The Italian Madrigal, describes the same piece (Segue cuor e non restare) as “remarkably awkward”. Two of the other frottolas published by Petrucci as anonymous have since been attributed to Fogliano.

Most of his frottolas were probably composed around 1500, which was around the peak time of production of that popular musical form. Like other frottolas, his were for four voices, using a simple homophonic texture, with the melody in the topmost voice. The two inner voices were usually filler and lacking in melodic interest, while the highest and lowest voices frequently moved in parallel tenths.

Fogliano began to write madrigals sometime in the mid-1530s, although dates of the individual works cannot be determined precisely. He published his one collection of madrigals, for five voices, in 1547. Stylistically many of these madrigals are like the frottolas he had written forty years before; a few others use a polyphonic style akin to the motet. While most of his madrigals are for five voices, most published in his one book, he wrote several for three voices. At least one of his madrigals appears in a Roman print by Andrea Antico dated 1537, an anthology of madrigals for three voices which includes works by Jacques Arcadelt and Costanzo Festa. One or two of the madrigals without attribution in the same collection may be by Fogliano as well.

Fogliano evidently wrote his motets and laude in the early 16th century, probably intending them to be performed by the singers at the cathedral. They are relatively simple and uncluttered in texture compared to similar works of the time from other musical centers, and are singable by amateurs or lightly trained musicians. As the singers in the provincial establishment at Modena were unlikely to have attained the levels of virtuosity found in places such as Ferrara and Venice, these pieces were well suited for this choir.

The keyboard ricercares, composed in the 1520s or 1530s and among the earliest examples of the form, are contrapuntal, in the manner of contemporary vocal music, but with shorter points of imitation. They include occasional ostinatos and scalewise flourishes, foreshadowing developments later in the century. Four of these pieces have survived, and were published in the 1940s in I classici musicali italiani (Milan).

Juan del Encina (12 July 1468 – 1529/1530) was a composer, poet, priest, and playwright, often credited as the joint-father (even “founder” or “patriarch”) of Spanish drama, alongside Gil Vicente. His birth name was Juan de Fermoselle. He spelled his name Enzina, but this is not a significant difference; it is two spellings of the same sound, in a time when “correct spelling” as we know it barely existed.

Even though his works were dedicated to royal families, he never served as a member of a royal chapel. Further, even though Encina worked in many cathedrals and was ordained as a priest, no religious musical works are known to still exist. Most of his works were done by his mid-30s, some 60 or more songs attributed to Encina, and another 9 settings of texts on top of that, to which the music could also be added, but not for certain. Many of the surviving pieces are villancicos, of which he was a leading composer. The Spanish villancico is the equivalent of the Italian Frottola. There are three and four voice settings that offer a variety of styles depending on the kind of text, with very limited movements in the voices in preparation for the cadence points. To make the text heard clearly, Encina used varied and flexible rhythms that are patterned on the accents of the verse, and used simple yet strong harmonic progressions.

Pierrequin de Thérache also Pierre or Petrus de Therache (c.1470-1528) was a French Renaissance composer from Nancy. Surviving works include three mass settings, three four-voice motets and a magnificat. His works are found in the Medici Codex of 1518, along with Costanzo Festa, Andreas de Silva, Jean Lhéritier, Johannes de la Fage, Jean Richafort, Adrian Willaert, Antoine Bruhier, Pierre Moulu, Jean Mouton, and others.

Francisco de Peñalosa (c. 1470 – April 1, 1528) was a Spanish composer of the middle Renaissance. Peñalosa was one of the most famous Spanish composers of the generation before Cristóbal de Morales, and his compositions were highly regarded at the time. Unfortunately for him, his music was not widely distributed; he did not benefit from the invention of printing, since he mostly remained in Spain, away from cities such as Venice and Antwerp which were the first centers of printed music. Later generations of Spanish composers—Guerrero, Morales, Victoria—went to Italy for parts of their careers, where their compositions were printed and were as widely distributed as the music of the Franco-Flemish composers who dominated music in Europe in the 16th century.

Peñalosa wrote masses, Magnificat settings, motets and hymns. Eleven secular compositions have survived, including an ensalada (a form of quodlibet) Por las sierras de Madrid for six voices.

Peñalosa was evidently fond of contrapuntal puzzles and canons, as evidenced by the quodlibet, and by the Agnus Dei of his Missa Ave Maria peregrina, which combines a plainsong tune with a retrograde (backwards) version of a famous secular song by Hayne van Ghizeghem.

One of his motets (Sancta mater istud agas) was long assumed to be by Josquin des Prez, which indicates both the stylistic similarity of their music and the high quality of Peñalosa’s.

Antoine de Févin (ca. 1470 – late 1511 or early 1512) was a Franco-Flemish composer of the Renaissance. He was active at the same time as Josquin des Prez, and shares many traits with his more famous contemporary.

All of Févin’s surviving music is vocal. He wrote masses, motets and chansons. Stylistically his music is similar to Josquin’s in its clarity of texture and design, and its relatively progressive nature: Févin evidently wrote in the most current styles, adopting the method of contrasting imitative sections with homophonic sections which came into prominence around 1490. Unlike Josquin, he was less concerned with the careful setting of text than with formal structure; his setting of individual words is occasionally clumsy, though his larger-scale structures are easy to follow. He also particularly liked the device of using vocal duets to contrast with the full sonority of the choir.

Some of Févin’s music uses the technique of free contrapuntal fantasy, later perfected by Josquin, where strict imitation is absent; fragments of a cantus firmus pervade the texture, giving a feeling of overall unity and complete equality of all the voices.

Of his music, 14 masses (one of which is a Requiem Mass), 3 lamentations, 3 Magnificats, 14 motets and 17 chansons survive.

Antonius Divitis (also Anthonius de Rycke, and Anthoine Le Riche – “the rich”) (c. 1470 – c. 1530) was a Flemish composer of the Renaissance, of the generation slightly younger than Josquin des Prez. He was important in the development of the parody mass.

Surviving works by Divitis include masses, motets, Magnificat settings (a genre that was to become quite popular in the middle 16th century), and a chanson. The three masses by Divitis use parody technique, and are among the first to do so; he is cited as influential in development of the genre, along with Jean Mouton and the other members of the French royal chapel. Each of his masses is for four voices, although an isolated six-voice setting of the Credo survives attributed to him. One of them, Missa Gaude Barbara, is based on a motet of that name by Mouton, and may have been a tribute to his colleague.

Motets by Divitis are often for five and six voices, which was another relatively innovative feature in music around the beginning of the 16th century. They are contrapuntal in texture, and two of them (Ista est speciosa and Per lignum crucis) are entirely canonic. His setting of the Marian antiphon Salve regina uses an identical tenor line, rests and all, to that which appears in Josquin’s setting of the popular song Adieu mes amours; it is uncertain whether Divitis consciously based his setting on Josquin, or on the popular song, which probably came first.

Bartolomeo Tromboncino (c. 1470 – 1535 or later) was an Italian composer of the middle Renaissance. He is mainly famous as a composer of frottole; he is principally infamous for murdering his wife. He was born in Verona and died in or near Venice.

In spite of his stormy, erratic, and possibly criminal life, much of his music is in the light current form of the frottola, a predecessor to the madrigal. He was a trombonist, as shown by his name, and sometimes employed in that capacity; however he apparently wrote no strictly instrumental music (or none survives). He also wrote some serious sacred music: seventeen laude, a motet and a setting of the Lamentations of Jeremiah. Stylistically, the sacred works are typical of the more conservative music of the early 16th century, using non-imitative polyphony over a cantus firmus, alternating sectionally with more homophonic textures or with unadorned plainsong. His frottolas, by far the largest and most historically significant part of his output (176 in all) are more varied than those of the other famous frottolist, Marchetto Cara, and they also tend to be more polyphonic than is typical for most frottolas of the time; in this way they anticipate the madrigal, the first collections of which began to be published near the very end of Tromboncino’s life, and in the city where he lived (for example Verdelot’s Primo libro di Madrigali of 1533, published in Venice). The major differences between the late frottolas of Tromboncino and the earliest madrigals were not so much musical as in the structure of the verse they set.

The poetry that Tromboncino set tended to be by the most famous writers of the time; he set Petrarch, Galeotto, Sannazaro, and others; he even set a poem by Michelangelo, Come haro dunque ardire, which was part of a collection Tromboncino published in 1518.

Mathurin Forestier (c.1470-1535) was a French Renaissance composer.

Pierre Alamire (also Petrus Alamire; probable birth name Peter van den Hove; c. 1470 – 26 June 1536) was a German-Dutch music copyist, composer, instrumentalist, mining engineer, merchant, diplomat and spy of the Renaissance. He was one of the most skilled music scribes of his time, and many now-famous works of Franco-Flemish composers owe their survival to his renowned illuminated manuscript copies; in addition he was a spy for the court of Henry VIII of England.

Only one work is attributed with certainty to Alamire, a four-part instrumental piece Tandernaken op den Rijn; however his evident skill and experience as a composer suggests that many of the anonymous works of the time may be his.

Richard Sampson (c. 1470 – 1554) was an English clergyman and composer of sacred music. He was an Anglican bishop of Chichester, and subsequently of Coventry and Lichfield.

Carpentras (also Elzéar Genet, Eliziari Geneti) (ca. 1470 – June 14, 1548) was a French composer of the Renaissance. He was famous during his lifetime, and was especially notable for his settings of the Lamentations which remained in the repertory of the Papal Choir throughout the 16th century. In addition, he was probably the most prominent Avignon musician since the time of the ars subtilior at the end of the 14th century.

Carpentras composed several masses, numerous settings of the Magnificat, psalm settings, hymns, motets, and secular songs, as well as many settings of the Lamentations, which were his most famous work both during his lifetime and until 1587 when Palestrina was commissioned by the Counter-Reformation church to replace them. Stylistically, his music is typical of the generation after Josquin, smoothly polyphonic with pervasive imitation. Carpentras alternates points of imitation with homophonic sections, especially in his settings of the Lamentations.

Vincenzo Capirola (1474 – after 1548) was an Italian composer, lutenist and nobleman of the Renaissance. His music is preserved in an illuminated manuscript called the Capirola Lutebook, which is considered to be one of the most important sources of lute music of the early 16th century.

The Lutebook contains the earliest known examples of legato and non-legato indications, as well as the earliest known dynamic indications. The pieces vary from simple studies suitable for beginners on the instrument, to immensely demanding virtuoso pieces. There are also 13 ricercars in the book, which alternate passages in brilliant toccata style with passages in three-part counterpoint similar to that of the vocal music of contemporary composers such as Jacob Obrecht.

In addition to music by Capirola (and others — Capirola evidently transcribed several pieces by other composers for the book), the Lutebook contains a preface which is one of the most important primary sources on early 16th century lute-playing. It includes information on how to play legato and tenuto, and how to perform ornaments of various types, how to choose the best fingering for passagework. It also includes very practical details such as how to string and tune the instrument.

Robert Cowper or Robert Cooper (c. 1474–1539/40) was an English composer. He studied music at the University of Cambridge and sang as a lay-clerk there in the Choir of King’s College. He was later appointed master of the choristers of the household chapel of Lady Margaret Beaufort.

He composed both sacred and secular music, including masses, motets and madrigals. The Gyffard partbooks contain a four part setting of Hodie composed by Cowper with John Taverner and Thomas Tallis.