Your cart is currently empty!

A History of Western Art Music

Chapter One: The Middle Ages

Content adapted from Wikipedia, licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0.

Medieval music encompasses the sacred and secular traditions of Western Europe during the Middle Ages, spanning approximately the 6th to the 15th centuries. As the first and longest major era in the history of Western classical music, it laid the foundation for the musical developments that would follow in the Renaissance and beyond. Together, the medieval and Renaissance periods are commonly referred to as “early music”—a broad term used by musicologists to distinguish these earlier styles from the later common-practice period.

Scholars often divide the medieval period into three distinct phases: the Early Middle Ages (c. 500–1000), the High Middle Ages (c. 1000–1300), and the Late Middle Ages (c. 1300–1400). Each of these stages witnessed significant musical developments, from the dominance of monophonic chant in the early centuries to the increasingly complex polyphony that emerged in the later Middle Ages. The repertory includes sacred vocal music such as Gregorian chant, which was sung by monks during the Catholic Mass, as well as secular songs, choral compositions, and instrumental works. Much of the surviving music from the early period is religious and vocal, reflecting the central role of the Church in cultural life.

Crucially, the medieval period saw the birth of music notation in the West. Before this innovation, music had to be transmitted orally—passed from one musician to another by rote. The emergence of notational systems made it possible to preserve, teach, and disseminate music with far greater accuracy and ease. This development was not only practical but transformative, enabling composers to create increasingly complex works involving multiple voices and precise rhythms. The theoretical groundwork laid during this era—including early explorations of polyphony and rhythmic modes—provided the structural basis for later Western musical traditions.

In sum, medieval music represents a formative chapter in Western music history. Despite the distance in time and style from modern ears, it introduced many of the key concepts—notation, modality, polyphony, and formal structure—that continue to influence Western art music to this day.

The above playlist contains selected works by some of the composers covered in the remainder of this chapter. The numbers that appear before the names of compositions in the text below refer to their position in the playlist. There are also separate playlists for each composer which contain all of the recordings available on Spotify barring those that are arrangements for modern instruments, instrumental arrangements of pieces originally scored for voices and the like.

Early Medieval Music (500-1000)

Chant, or plainsong, is a monophonic form of sacred music that represents the earliest known musical tradition of the Christian Church. Sung in unison without instrumental accompaniment, chant served a liturgical purpose and was central to worship across medieval Europe. While Gregorian chant is the best-known form today, several regional chant traditions developed independently, each shaped by the liturgical practices of its locale. Among the most prominent centers were Rome, Hispania, Gaul, Milan, and Ireland, each of which cultivated its own repertoire and customs for celebrating the Mass.

By the late 9th century, monastic communities such as the Abbey of St. Gall in Switzerland began to experiment with enriching plainchant by adding a second vocal line. This practice, known as organum, typically involved a second voice moving in parallel motion a fourth or fifth above the original chant. Though modest at first, these early experiments marked the beginnings of polyphony and laid the groundwork for Western musical concepts of counterpoint and harmony. Over time, organum evolved to include more complex and independent voice parts, leading to increasingly elaborate musical textures.

Another important development in early medieval music was the emergence of the liturgical drama. Rooted in the embellishment of chant texts—known as tropes—these musical dramas often depicted scenes from the Bible or other Christian narratives. Likely originating in the 10th century, liturgical dramas were performed within the context of church services and combined music, poetry, and staging. They represent a vital link between sacred chant traditions and the later development of medieval theatrical and musical forms.

Composers of the Early Middle Ages

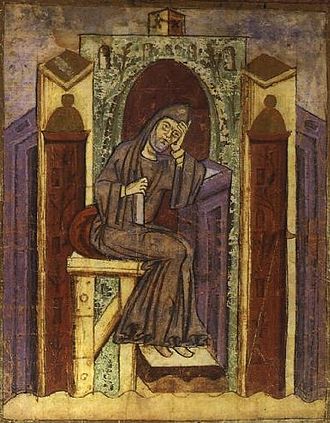

Notker Balbulus (c. 840 – 6 April 912), Notker the Stammerer or simply Notker, was a Benedictine monk at the Abbey of Saint Gall in modern-day Switzerland. Described as “a significant figure in the Western Church”, Notker made substantial contributions to both the music and literature of his time. The anonymous piece included in the playlist originates from the St. Gall manuscripts held in the Abbey library of Saint Gall and were composed around the same time as Notker’s.

- Natus ante saecula

- Ex numero frequentium – Quasi quid incredibile – Qui vobis terrigenis

Anonymous

- In omnem terram (St. Gall c. 922-926)

Tuotilo (died 27 April 915) was a Frankish monk at the Abbey of Saint Gall. He was a composer, and according to Ekkehard IV a century later, also a poet, musician, painter and sculptor. Various trope melodies can be assigned to Tuotilo, but works of other mediums are attributed with less certainty. He was a student of Iso of St. Gallen and friends with the fellow monk Notker Balbulus. Tuotilo played several instruments, including the harp. The history of the ecclesiastical drama begins with the trope sung as Introit of the Mass on Easter Sunday. It has come down to us in a St. Gallen manuscript dating from the time of Tuotilo. According to the works catalogue of Ekkehard IV, Casus sancti Galli, Tuotilo is the author of five tropes; further research ascribed five additional tropes to him.

Fulbert de Chartres (c. 952–10 April 1028) French or Italian, Bishop of Chartres in France from 1006 to 1028 and a teacher at the Cathedral school there.

William of Volpiano (962 – 1 January 1031) was a Northern Italian monastic reformer, composer, and founding abbot of numerous abbeys in Burgundy, Italy and Normandy.

Wipo of Burgundy (c.995– c.1050) was a priest, poet and chronicler. The well-known musical sequence, Victimae paschali laudes is often attributed to him, though its authenticity remains uncertain.

High Medieval Music (1000–1300)

The flowering of the Notre Dame school of polyphony from around 1150 to 1250 corresponded to the equally impressive achievements in Gothic architecture: indeed the centre of activity was at the cathedral of Notre Dame itself. Sometimes the music of this period is called the Parisian school, or Parisian organum, and represents the beginning of what is conventionally known as ars antiqua. This was the period in which rhythmic notation first appeared in Western music, mainly a context-based method of rhythmic notation known as the rhythmic modes. This was also the period in which concepts of formal structure developed which were attentive to proportion, texture, and architectural effect. Composers of the period alternated florid and discant organum (more note-against-note, as opposed to the succession of many-note melismas against long-held notes found in the florid type), and created several new musical forms: clausulae, which were melismatic sections of organa extracted and fitted with new words and further musical elaboration; conductus, which were songs for one or more voices to be sung rhythmically, most likely in a procession of some sort; and tropes, which were additions of new words and sometimes new music to sections of older chant. All of these genres save one were based upon chant; that is, one of the voices, (usually three, though sometimes four) nearly always the lowest (the tenor at this point) sang a chant melody, though with freely composed note-lengths, over which the other voices sang organum. The exception to this method was the conductus, a two-voice composition that was freely composed in its entirety. The motet, one of the most important musical forms of the High Middle Ages, Late Middle Ages and Renaissance, developed initially during the Notre Dame period out of the clausula, especially the form using multiple voices as elaborated by Pérotin.

Composers of the High Middle Ages

Godric of Finchale (c. 1065–21 May 1170) was an English hermit, merchant and popular medieval saint, although he was never formally canonized. He was born in Walpole in Norfolk and died in Finchale in County Durham. Reginald of Durham recorded four songs of St Godric’s: they are the oldest songs in English for which the original musical settings survive.

Adam of Saint Victor (c. 1068–1146) was a prolific composer and poet of Latin hymns. A central figure of the sequences in high medieval music, he has been called “…the most illustrious exponent of the revival of liturgical poetry which the twelfth century affords.” Adam’s career was based in Paris, split between the Abbey of Saint Victor and Notre Dame. He was well acquainted with numerous contemporary scholars and musicians, including the philosopher and composer Peter Abelard, the theologian Hugh of Saint Victor and the composer Albertus Parisiensis, the last possibly being his student.

Peter Abelard (c. 1079–21 April 1142) was a medieval French scholastic philosopher, leading logician, theologian, poet, composer and musician.

Hildegard von Bingen (c. 1098 – 17 September 1179) was a German Benedictine abbess active as a writer, composer, philosopher, mystic, visionary, and medical writer and practitioner during the High Middle Ages. She is one of the best-known composers of sacred monophony, as well as the most recorded in modern history. Attention in recent decades to women of the medieval Catholic Church has led to a great deal of popular interest in Hildegard’s music. In addition to the Ordo virtutum, sixty-nine musical compositions, each with its own original poetic text, survive, and at least four other texts are known, though their musical notation has been lost. This is one of the largest repertoires among medieval composers. One of her better-known works, Ordo virtutum (Play of the Virtues), is a morality play. It is uncertain when some of Hildegard’s compositions were composed, though the Ordo virtutum is thought to have been composed as early as 1151. It is an independent Latin morality play with music (82 songs); it does not supplement or pay homage to the Mass or the Office of a certain feast. It is, in fact, the earliest known surviving musical drama that is not attached to a liturgy. In addition to the Ordo virtutum, Hildegard composed many liturgical songs that were collected into a cycle called the Symphonia armoniae celestium revelationum. The songs from the Symphonia are set to Hildegard’s own text and range from antiphons, hymns, and sequences, to responsories. Her music is monophonic and its style has been said to be characterized by soaring melodies that can push the boundaries of traditional Gregorian chant and to stand outside the normal practices of monophonic monastic chant. Another feature of Hildegard’s music that both reflects the twelfth-century evolution of chant, and pushes that evolution further, is that it is highly melismatic, often with recurrent melodic units.

- Cum vox sanguinis

- Hodie aperuit nobis clausa porta

- Laus Trinitati

- O choruscans lux stellarum

Notre Dame School

The reign of Louis VII (1137–1180) witnessed a period of cultural innovation, in which appeared the Notre Dame school of musical composition, and the contributions of Léonin, who prepared two-part choral settings (organa) for all the major liturgical festivals. This period in musical history has been described as a paradigm shift of lasting consequence in musical notation and rhythmic composition, with the development of the organum, clausula, conductus and motet. The innovative nature of the Notre Dame style stands in contrast to its predecessor, that of the Abbey of St Martial, Limoges, replacing the monodic (monophonic) Gregorian chant with polyphony (more than one voice singing at a time). This was the beginning of polyphonic European church music.

Organum at its roots involves simple doubling (organum duplum or organum purum) of a chant at intervals of a fourth or fifth, above or below. This school also marked a transition from music that was essentially performance to a less ephemeral entity that was committed to parchment, preserved and transmitted to history. It is also the beginning of the idea of composers and compositions, the introduction of more than two voices and the treatment of vernacular texts. For the first time, rhythm became as important as pitch, to the extent that the music of this era came to be known as musica mensurabilis (music that can be measured). These developments and the notation that evolved laid the foundations of musical practice for centuries.

The surviving manuscripts from the thirteenth century together with the contemporaneous treatises on musical theory constitute the musical era of ars antiqua. The Notre Dame repertory spread throughout Europe. In Paris polyphony was being performed in the late 1190s but later sources imply that some of the compositions date back as far as the 1160s. Although often linked to the construction of the cathedral itself, construction commenced in 1163 and the altar consecrated in 1182. However, there was evidence of musical creativity there from the early twelfth century.

Léonin’s work was distinguished by two distinctive organum styles, purum and discantus. This early polyphonic organa was still firmly based on Gregorian chant, to which a second voice was added. The chant was called the tenor (cantus firmus or vox principalis), which literally “holds” (Latin: tenere) the melody. The tenor is based on an existing plainsong melody from the liturgical repertoire (such as the Alleluia, Verse or Gradual, from the Mass, or a Responsory or Benedicamus from the Office). This quotation of plainchant melody is a defining characteristic of thirteenth century musical genres. In organum purum the tenor part was drawn out into long pedal points, while the upper part or duplum contrasted with it in a much freer rhythm, consisting of melisms (melismatic or several notes per syllable, compared to syllabic, a single note per syllable). In the second, discantus, style, the tenor was allowed to be melismatic, and the notes were quicker and more regular with the upper part becoming equally rhythmic. These more rhythmic sections were known as clausulae (puncta). Another innovation was the standardization of note forms, and Léonin’s new square notes were quickly adopted. Although he developed the discantus style, Léonin’s strength was as a writer of organum purum. The singing of organa fell into disuse by the mid thirteenth century.

Associated with the Notre Dame school, was Johannes de Garlandia, whose De mensurabili provided a theoretical basis, for Notre Dame polyphony is essentially musica mensurabilis, music that is measured in time. In his treatise, he defines three forms of polyphony, organum in speciali, copula, and discant, which are defined by the relationship of the voices to each other and by the rhythmic flow of each voice.

Léonin compiled his compositions into a book, the Magnus liber organi (Great Organum Book), around 1160. Pérotin’s works are preserved in this compilation of early polyphonic church music, which was in the collection of the cathedral of Notre Dame in Paris. The Magnus liber also contains the work of his successors. In addition to two-part organa, this book contains three- and four-part compositions in four distinct forms: organa, clausulae, conducti and motets, and three distinct styles. In the organum style the upper voices are highly mobile over a tenor voice moving in long unmeasured notes. The discant style has the tenor moving in measured notes, but still more slowly than the upper voices. The third style has all voices moving note on note, and is largely limited to conductus. The surviving sources all commence with a four-voice organal setting of the Christmas Gradual, Viderunt omnes fines terrae (lit. ‘All the ends of the earth have seen‘), believed to be Pérotin’s, as most likely did the original Liber. However, the manuscripts and fragments that survive date well into the thirteenth century, meaning that they are preserved in a form notated by musicians working several generations following Léonin and Pérotin. This collection of music constitutes the earliest known record of polyphony to have the stability and circulation achieved earlier by monophonic Gregorian chant.

Léonin (fl. 1135–1201) was the first known significant composer of polyphonic organum. He was probably French, probably lived and worked in Paris at the Notre-Dame Cathedral and was the earliest member of the Notre Dame school of polyphony and the ars antiqua style who is known by name. All that is known about him comes from the writings of a later student at the cathedral known as Anonymous IV, an Englishman who left a treatise on theory and who mentions Léonin as the composer of the Magnus Liber, the “great book” of organum.

Much of the Magnus Liber is devoted to clausulae—melismatic portions of Gregorian chant which were extracted into separate pieces where the original note values of the chant were greatly slowed down and a fast-moving upper part is superimposed. Léonin might have been the first composer to use the rhythmic modes, and may have invented a notation for them. According to W.G. Waite, writing in 1954: “It was Léonin’s incomparable achievement to introduce a rational system of rhythm into polyphonic music for the first time, and, equally important, to create a method of notation expressive of this rhythm.” The Magnus Liber was intended for liturgical use.

According to Anonymous IV, “Magister Leoninus (Léonin) was the finest composer of organum; he wrote the great book (Magnus Liber) for the gradual and antiphoner for the sacred service.” All of the Magnus Liber is for two voices, although little is known about actual performance practice: the two voices were not necessarily soloists.

- Sedit Angelus

Albertus Parisiensis (fl. 1146–1177), also known as Albert of Paris, was a French cantor and composer. He is credited with creating the first known piece of European music for three voices. The only extant piece of his is the conductus Congaudeant Catholici. The piece was part of the Codex Calixtinus, a work intended as a guide for travelers making the Way of St. James, a pilgrimage to a shrine in Santiago de Compostela.

- Congaudeant Catholici

Philippe le Chancelier (c. 1160–December 26, 1236) was a French theologian, Latin lyric poet, and possibly a composer as well, although it is not certain, since many of his works are set to pre-existing tunes. He put text to many of Pérotin’s works, creating some of the first Motets.

Pérotin (fl. c. 1200) was a composer associated with the Notre Dame school of polyphony in Paris and the broader ars antiqua musical style of high medieval music. He is credited with developing the polyphonic practices of his predecessor Léonin, with the introduction of three and four-part harmonies.

Pérotin is best known for his composition of both liturgical organa and non-liturgical conducti in which the voices move note on note. He pioneered the styles of organum triplum and organum quadruplum (three and four-part polyphony) and his Viderunt omnes and Sederunt principes et adversum me loquebantur (lit. ‘Princes sat and plotted against me’), Graduals for Christmas and the feast of St Stephen’s Day (26 December) respectively are among only a few organa quadrupla known, early polyphony having been restricted to two-part compositions. With the addition of further parts, the compositions became known as motets, the most important form of polyphony of the period. Pérotin’s two Graduals for the Christmas season represent the highest point of his style, with a large scale tonal design in which the massive pedal points sustain the swings between consecutive harmonies, and an intricate interplay among the three upper voices. Pérotin also furthered the development of musical notation, moving it further from improvisation. Despite this, we know nothing of how these works came about.

In addition to his own compositions, as noted by Anonymous IV, Pérotin set about revising the Magnus liber organi. Léonin’s added duplum required skill, and had to be sung fast with up to 40 notes to one of the underlying chant, as a result of which the actual text progressed very slowly. Pérotin shortened these passages, while adding further voice parts to enrich the harmony. The degree to which he did this has been debated due to the phrase abbreviavit eundem by Anonymous IV. Usually translated as abbreviate, it has been surmised that he shortened the Magnus liber by replacing organum purum with discant clausulae or simply replacing existing clausulae with shorter ones. Some 154 clausulae have been attributed to Pérotin but many other clausulae are elaborate compositions that would actually expand the compositions in the Liber, and these stylistically resemble his known works which are on a much grander scale than those of his predecessor, and hence do not represent “abbreviation”. An alternative rendering of abbreviavit is to write down, suggesting that he actually prepared a new edition using his better developed system of rhythmic notation, including mensural notation, as mentioned by Anonymous IV.

Two styles emerged from the organum duplum, the “florid” and “discant” (discantus). The former was more typical of Léonin, the latter of Pérotin, though this indirect attribution has been challenged. Anonymous IV described Léonin as optimus organista (the best composer of organa) but Pérotin, who revised the former’s Magnus liber organi (Great Organum Book), as optimus discantor referring to his discant composition. In the original discant organum duplum, the second voice follows the cantus firmus, note on note but at an interval, usually a fourth above. By contrast, in the florid organum, the upper or vox organalis voice wove shorter notes around the longer notes of the lower tenor chant.

Most of Pérotin’s works are in polyphonic form of discant, including the quadrupla and tripla. Here the upper voices move in discant, as rhythmic counterpoint above the sustained tenor notes. This is consistent with Anonymous IV’s description of him as optimus discantor. However, like Léonin, he is likely to have composed in every musical genre and style known to Notre Dame polyphony.

Pérotin has been described as the first modern composer in the Western tradition, radically transforming the work of his predecessors from a largely improvisatory technique to a distinct musical architecture. Pérotin’s music has influenced modern minimalist composers such as Steve Reich, particularly in Reich’s work Proverb.

- Feast of St. Stephen: Sederunt principes – Adiuva me, Domine (à 4) (Gradual)

Wincenty of Kielcza (c. 1200 – after 1262) was a Polish canon, poet, and composer, working in Kraków and writing in Latin. He was a member of the Dominican Order. He is best known for his hymn “Gaude Mater Polonia”.

Alfonso X of Castile (also known as El Sabio; 23 November 1221 – 4 April 1284) commissioned or co-authored numerous works of music during his reign. These works included Cantigas d’escarnio e maldicer and the vast compilation Cantigas de Santa Maria (“Songs to the Virgin Mary”), which was written in Galician-Portuguese and figures among the most important of his works. The Cantigas de Santa Maria form one of the largest collections of vernacular monophonic songs to survive from the Middle Ages. They consist of 420 poems with musical notation. The poems are for the most part on miracles attributed to the Virgin Mary. One of the miracles Alfonso relates is his own healing in Puerto de Santa María.

Petrus de Cruce (c. 1250 – also Pierre de la Croix) was active as a cleric, composer and music theorist in the late part of the 13th century. His main contribution was to the notational system. Mensural notation had developed by fits and starts during the 13th century as the old ligatures/rhythmic modes became, for various reasons, less suited to the indication of polyphony’s new subtleties, as we shall see below. Not the least problem was that notation in individual part-books was cheaper than notation in score (since each piece took up much less overall space), so a way had to be found of doing it—this would involve the development of a reliable system by which to indicate note-by-note metrical value. The beginning of such a solution was Franconian notation, so called after the theorist Franco of Cologne, who outlined the system in his c. 1260 treatise, Ars cantus mensurabilis (The art of mensurable music). This system recognized the double-long (octuple whole note), long (quadruple whole note), breve (double whole note), and semi-breve (whole note) as the units of note value, related to one another by triple grouping; the double was always worth two longs, but a long could be perfect (and therefore worth three breves) or imperfect (and worth only two), depending on the exact sequence of notes. The breve was the “tempus”, equivalent to the ‘unit of the beat’ in modern notation (three quarters to a measure in ¾ time, etc.), or a modern measure if we consider all of the music to have been in 3/1, so perfect tempus was triple meter, and imperfect tempus would be duple once introduced. A breve could theoretically be worth either three semi-breves or two in Franconian notation, but if worth two, one or the other would be doubled in length. There was no provision in this notation for equal duple division, which (along with imperfect tempus, therefore) would have to wait until de Vitry codified the concept of prolation in his Ars nova of 1322.

By the 1280s, tripla (the top parts of motets and other polyphonic pieces) were moving more rapidly and independently than before, with the chant-based tenors becoming slower moving, supporting parts. Since composers wanted to maintain speech rhythms in their tripla, they looked for a way to divide the tempus into more than three semi-breves, which in modern notation would be the equivalent of a tuplet (triplet, quartolet, quintuplet, etc.); motets which do this bear the name “Petronian”, after the most prominent user of the style. One way of indicating this division was to line up the voices one atop another in score notation, so that the tempus could be seen by examining the lower parts, still wedded to rhythmic mode. This would have been a waste of precious resources, however, and was no more an option now than it had been before. Petrus, who often divided his breves into as many as seven semi-breves, developed the dot of division (punctum divisionis), which are dots placed in between semi-breves to group them; thus a series of five semi-breves separated by dots from those surrounding them would be understood by the reader as occurring in the space of one breve. In later, 15th and 16th century notation, confusion between dots of division and the later innovation of dots indicating extended note values creates transcription problems for editors, but it is usually possible to tell from context, as well as prevailing tempus and prolation, which is meant; indeed, the dot of division is rarely required, since a run of semi-breves coming between two ligatures is clearly a grouping.

Petrus’s free usage of the divided breve had far-reaching implications for musical style. With more notes, the triplum became the most prominent of the three voices in contemporary texture, and the other two were relegated to a supporting role. Also, more notes and more intricate subdivision led to a slowing of general tempo—the semi-breve was performed more slowly than it had been in earlier practice, becoming the true unit of the beat, and the lower voices lost their rhythmic vitality, becoming mere structural successions of breves and longs.

Composed around 1300, Petronian motets are still considered part of the ars antiqua. Characteristics include further division of the triplum, the motetus and triplum move toward light and elegant expression, and a lack of concern for principles of proper textual accentuation.

- Aucun ont trouvé

- S’amours eûst point de poer

Late Medieval Music (1300–1400)

The beginning of the ars nova is one of the few clear chronological divisions in medieval music, since it corresponds to the publication of the Roman de Fauvel, a huge compilation of poetry and music, in 1310 and 1314. The Roman de Fauvel is a satire on abuses in the medieval church, and is filled with medieval motets, lais, rondeaux and other new secular forms. While most of the music is anonymous, it contains several pieces by Philippe de Vitry, one of the first composers of the isorhythmic motet, a development which distinguishes the fourteenth century. The isorhythmic motet was perfected by Guillaume de Machaut, the finest composer of the time.

During the ars nova era, secular music acquired a polyphonic sophistication formerly found only in sacred music, a development not surprising considering the secular character of the early Renaissance (while this music is typically considered “medieval”, the social forces that produced it were responsible for the beginning of the literary and artistic Renaissance in Italy—the distinction between Middle Ages and Renaissance is a blurry one, especially considering arts as different as music and painting). The term “ars nova” (new art, or new technique) was coined by Philippe de Vitry in his treatise of that name (probably written in 1322), in order to distinguish the practice from the music of the immediately preceding age.

The dominant secular genre of the ars nova was the chanson, as it would continue to be in France for another two centuries. These chansons were composed in musical forms corresponding to the poetry they set, which were in the so-called formes fixes of rondeau, ballade, and virelai. These forms significantly affected the development of musical structure in ways that are felt even today; for example, the ouvert-clos rhyme-scheme shared by all three demanded a musical realization which contributed directly to the modern notion of antecedent and consequent phrases. It was in this period, too, in which began the long tradition of setting the Ordinary of the Mass. This tradition started around mid-century with isolated or paired settings of Kyries, Glorias, etc., but Machaut composed what is thought to be the first complete mass conceived as one composition. The sound world of ars nova music is very much one of linear primacy and rhythmic complexity. “Resting” intervals are the fifth and octave, with thirds and sixths considered dissonances. Leaps of more than a sixth in individual voices are not uncommon, leading to speculation of instrumental participation at least in secular performance.

Composers of the Late Middle Ages

Philippe de Vitry (31 October 1291 – 9 June 1361) was a French composer-poet, bishop and music theorist in the ars nova style of late medieval music. An accomplished, innovative, and influential composer, he was widely acknowledged as a leading musician of his day, with Petrarch writing a glowing tribute, calling him: “… the keenest and most ardent seeker of truth, so great a philosopher of our age.” It is thought that very little of Vitry’s compositions survive; though he wrote secular music, only his sacred works are extant.

Philippe de Vitry is most famous in music history for the Ars nova notandi (1322), a treatise on music attributed to him that lent its name to the music of the entire era. While his authorship and the very existence of this treatise have recently come into question, a handful of his musical works do survive and show the innovations in musical notation, particularly mensural and rhythmic, with which he was credited within a century of their inception. Such innovations as are exemplified in his stylistically attributed motets for the Roman de Fauvel were particularly important, and made possible the free and quite complex music of the next hundred years, culminating in the ars subtilior. In some ways the “modern” system of rhythmic notation began with the ars nova, during which music might be said to have “broken free” from the older idea of the rhythmic modes, patterns which were repeated without being individually notated. The notational predecessors of modern time meters also originate in the ars nova.

He is reputed to have written chansons and motets, but only some of the motets have survived. Each is strikingly individual, exploiting a unique structural idea. He is also often credited with developing the concept of isorhythm (an isorhythmic line consists of repeating patterns of rhythms and pitches, but the patterns overlap rather than correspond; e.g., a line of thirty consecutive notes might contain five repetitions of a six-note melody or six repetitions of a five-note rhythm). Five of his three-part motets have survived in the Roman de Fauvel; an additional nine can be found in the Ivrea Codex.

- Petre Clemens, tam re quam nimine – Lugentium siccentur occuli plaudant senes

- Tribum, que non abhorruit – Quoniam secta latronum – Merito hec patimur

- Vos quid admiramini, virgenes – Gratissima virginis species – Gaude gloriosa

- Tuba sacre fidei – In arboris

- Almifonis melos – Rosa sine culpe spina (attributed to Vitry but not widely accepted)

Jehan de Lescurel (fl. early 14th century; also Jehannot de l’Escurel) was a composer-poet of late medieval music. Jehan’s extensive surviving oeuvre is an important and rare examples of the formes fixes before the time of Guillaume de Machaut; it consists of 34 works: 20 ballades, 12 rondeaus and two long narrative poems, diz entés. All but one of his compositions is monophonic, representing the end of the trouvère tradition and the beginning of the polyphonic ars nova style centered around the formes fixes.

- A vous, douce debonnaire

- Toy servir en humilité

Marchetto da Padova (fl. 1305 – 1319) was an Italian music theorist and composer of the late medieval era. His innovations in notation of time-values were fundamental to the music of the Italian ars nova, as was his work on defining the modes and refining tuning. In addition, he was the first music theorist to discuss chromaticism.

Only three motets have been reliably attributed to Marchetto, one of them due to his name appearing as an acrostic in the text for one of the parts (Ave regina celorum/Mater innocencie). Based on another acrostic in the same motet, it seems it was composed for the dedication of the Scrovegni Chapel (also known as the Arena Chapel) in Padua on March 25, 1305.

Marchetto’s innovations are in three areas: tuning, chromaticism, and notation of time-values. He was the first medieval writer to propose dividing the whole tone into more than two parts. A semitone could consist of one, two, three, or four of these parts, depending on whether it was, respectively, a diesis, an enharmonic semitone, a diatonic semitone, or a chromatic semitone. Marchetto preferred to widen major intervals and narrow minor ones for melodic effect, the opposite of what the later meantone temperament does.

In the area of time values, Marchetto improved on the old Franconian system of notation; music notation was by this time evolving into the method known today where an individual symbol represented a specific time-value, and Marchetto contributed to this trend by developing a method of compound time division, and by assigning specific note shapes to specific time values.

Additionally, Marchetto discussed the rhythmic modes, an old rhythmic notation method from the 13th-century ars antiqua, and added four “imperfect” modes to the existing five “perfect” modes, thus allowing for the contemporary Italian practice of mixed, flexible and expressive rhythmic performance.

Marchetto’s treatises were hugely influential in the 14th and early 15th centuries, and were widely copied and disseminated. The Rossi Codex, which is the earliest surviving source of secular Italian polyphony and which contains music written between 1325 and 1355, shows obvious influence of Marchetto, especially in its use of his notational improvements.

Without the innovations of Marchetto, the music of the Italian Trecento – for example the secular music of Landini – would not have been possible.

Guillaume de Machaut (c. 1300 – April 1377) was a French composer and poet who was the central figure of the ars nova style in late medieval music. His dominance of the genre is such that modern musicologists use his death to separate the ars nova from the subsequent ars subtilior movement. Regarded as the most significant French composer and poet of the 14th century, he is often seen as the century’s leading European composer.

Machaut, one of the earliest European composers on whom considerable biographical information is available, has an unprecedented amount of surviving music, in part due to his own involvement in his manuscripts’ creation and preservation.Machaut embodies the culmination of the poet-composer tradition stretching back to the traditions of troubadour and trouvère. Machaut composed in a wide range of styles and forms and was crucial in developing the motet and secular song forms (particularly the lai and the formes fixes: rondeau, virelai and ballade). Among his only surviving sacred works, Messe de Nostre Dame, is the earliest known complete setting of the Ordinary of the Mass attributable to a single composer.

- Plourez, dames, plourez vostre servant (Ballade from “Le Voir dit”)

- Puisqu’en oubli suis de vous, dous amis (Three-voice rondeau)

- Motet no. 5: Fias volontas tua

- Motet no. 7: Ego moriar pro te

- De Fortune me doi pleindre et loer (Three-voice ballade)

- Mors sui, se je ne vous voy

- Lasse! comment oublieray/Se j’aim mon loial amy/Pour quoy me bat mes maris?, Motet 16

Jacopo da Bologna (fl. 1340 – c. 1386) was an Italian composer of the Trecento, the period sometimes known as the Italian ars nova. He was one of the first composers of this group, making him a contemporary of Gherardello da Firenze and Giovanni da Cascia. He concentrated mainly on madrigals, including both canonic (caccia-madrigal) and non-canonic types, but also composed a single example each of a caccia, lauda–ballata, and motet. Jacopo’s ideal was “suave dolce melodia” (sweet, gentle melody). His style is marked by fully texted voice parts that never cross. The untexted passages which connect the textual lines in many of his madrigals are also noteworthy.

- Lux purpurata radiis; Diligite iustitiam (Three-voice motet)

- Nel bel giardino che l’Adige (Madrigal)

Maestro Piero (Magister Piero or Piero) (born before 1300, died shortly after 1350) was an Italian composer of the late medieval era. He was one of the first composers of the Trecento who is known by name, and probably one of the oldest. He is mainly known for his madrigals.

A total of eight compositions by Piero have survived, plus two more cacce (canons) which have been attributed to him based on stylistic similarities. All eight are secular pieces: six madrigals, and two cacce. All eight of the attributed compositions are preserved in the Biblioteca Nazionale in Florence. Two of his works are preserved in the Rossi Codex.

Piero’s madrigals are the earliest surviving works in that form which are canonic. The madrigals are for two voices, and the two cacce are for three; what distinguishes his work from that of his contemporaries is his frequent use of canon, especially in the ritornello passages in his madrigals. Piero’s works clearly show the evolution of the three-voice canonic caccia form from the madrigal, in which the canonic portion of the madrigal became a two-voice canon, over a tenor, characteristic of the caccia.

Giovanni da Cascia (fl. 1340–1350) was an Italian composer of the late medieval era, active in the middle of the fourteenth century. Nineteen of Giovanni’s compositions survive, scattered in nine manuscripts. Sixteen of these are madrigals, and three of them are cacce. He is thought to have written some of his own texts. Musically, Giovanni’s madrigals are of importance in the development of the style of the 14th-century madrigal. He tends to use extended melismas on the first and penultimate syllables of a poetic line, and sometimes introduces hockets at these points. The middles of the lines are generally syllabic. Many of his works are very similar in style to the anonymous works preserved in the Rossi Codex.

Several of his works survive in quite different versions; this is evidence that improvisation was still an important aspect of musical performance up to this time. Giovanni’s works tend not to be tonally unified; they begin and end on different notes, and in some cases, such as Nascoso el viso, each poetic line begins and ends on different notes. Occasional imitation is found in his work.

Vincenzo da Rimini (fl. 1350) was an Italian composer of the late medieval era. Six of Vincenzo’s pieces survive to the present day: four of them are madrigals and two are cacce. Stylistic indications place Vincenzo as younger than Jacopo da Bologna and older than Lorenzo da Firenze and Donato da Cascia. Vincenzo makes more use of imitation in the madrigals than did Jacopo. Both of his cacce, which use the dialect of North Italy, depict marketplace scenes.

P. des Molins (fl. mid 14th century) was a French composer-poet in the ars nova style of late medieval music. His two surviving compositions – the ballade De ce que fol pensé and rondeau Amis, tout dous vis – were tremendously popular as they are among the most transmitted pieces of fourteenth-century music. The ballade is found in 12 medieval manuscript sources and featured in a c. 1420 tapestry; the rondeau is found in 8 sources and referenced by the Italian poet Simone de’ Prodenzani. Along with Grimace, Jehan Vaillant and F. Andrieu, Molins was one of the post-Guillaume de Machaut generation whose music shows few distinctly ars subtilior features, leading scholars to recognize Molins’s work as closer to the ars nova style of Machaut.

Niccolò da Perugia (fl. c. 1350-1400) was an Italian composer of the Trecento, the musical period also known as the “Italian ars nova“. He was a contemporary of Francesco Landini, and apparently was most active in Florence.

A total of 41 compositions of Niccolò have survived with reliable attribution, the majority of them in the Squarcialupi Codex, and all the others from sources in Tuscany. All are secular, all are vocal, and they include 16 madrigals, 21 ballate, and 4 cacce. The madrigals are all for two voices, except for one which uses three, and all are in a relatively conservative style, uninfluenced by contemporary French practice (thereby differing from the similar works of Landini). Sacchetti’s records of his poetry that was set to music includes the titles of several other pieces by Niccolò that do not survive.

One peculiarity of Niccolò was the genre of the tiny ballata, the ‘ballatae minimae’. These pieces are very short, consisting of a single moralizing line of text, much different from the amorous love poetry set by other contemporary composers such as Landini.

Donato da Cascia (fl. c. 1350 – 1370) was an Italian composer of the Trecento. All of his surviving music is secular, and the largest single source is the Squarcialupi Codex. Seventeen compositions by Donato survive, including: fourteen madrigals, one caccia, one virelai, and one ballata. Except for one piece, his music is all for two voices, typical of mid-century practice in that regard, but unusually virtuosic; according to Nino Pirrotta, it “represents the peak of virtuoso singing in the Italian madrigal, and therefore in the Italian ars nova as a whole.”

Donato’s madrigals usually feature an upper voice part which is more elaborate than the lower, and often use imitation between the two voices, though usually the imitative passages are short. In addition he uses repeated words and phrases, often with a humorous intent; the influence of the caccia is evident in this device. Jacopo da Bologna was probably an influence on his work, as can be seen in the single-voiced transitional passages between different verses of the madrigals, typical of Jacopo.

Matheus de Sancto Johanne (died after 10 June 1391), also known as Mayshuet, was a French composer of the late medieval era. Active both in France and England, he was one of the representatives of the complex, manneristic musical style known as the ars subtilior, a musical style characterized by rhythmic and notational complexity, centered on Paris, Avignon in southern France, and also in northern Spain at the end of the fourteenth century. The style also is found in the French Cypriot repertory. Often the term is used in contrast with ars nova, which applies to the musical style of the preceding period from about 1310 to about 1370; though some scholars prefer to consider ars subtilior a subcategory of the earlier style. Primary sources for ars subtilior are the Chantilly Codex, the Modena Codex, and the Turin Manuscript.

Six of his compositions have survived with reliable attribution. They include an unusual motet for five voices, Ave post libamina/Nunc surgunt (very few motets of the period have more than four voices), and five secular works: three ballades and two rondeaux. Two of the ballades, and one of the rondeaux, are for three voices, and these are later compositions more associated with the ars subtilior style; the others are four voices, and were possibly written earlier. That he was well-appreciated in England can be seen in late copies of his motet made there around 1430, for example, in the Old Hall Manuscript.

Jehan Vaillant (fl. 1360–1390) was a French composer and music theorist. Besides five (possibly six) pieces of music surviving to his name, he was also the author of a treatise on tuning. Vaillant was part of the post-Machaut generation whose music shows few distinctly ars subtilior features, leading scholars to recognize Vaillant’s work as closer to the ars nova style of Machaut.

Vaillant may have been “a younger contemporary of Machaut”, but if, as the Chantilly Manuscript records, one of his rondeaux was copied in Paris in 1369, then he was “rhythmically in advance of Machaut’s style”. This rondeau has two texts, Dame doucement and Doulz amis, while another has three, Tres doulz amis, Ma dame and Cent mille fois. Two of his rondeaux are monotextual: Pour ce que je ne say, which is isorhythmic and pedagogical, and Quiconques veut, a polymetric piece that is actually anonymous but sometimes ascribed to Vaillant. Of his works, only the ballade Onques Jacob is “fully in the style of Machaut”.

Vaillant’s Par maintes foys, a virelai with imitation bird-calls, was probably one of the most popular works of the time, certainly one of the most copied, surviving in nine sources, including versions with two voices, an added cantus, a Latin contrafactum and one with a German contrafactum by Oswald von Wolkenstein.

Bartolino da Padova (also Magister Frater Bartolinus de Padua) (fl. c. 1365 – c. 1405) was an Italian composer of the late 14th century. He is a representative of the stylistic period known as the Trecento. The Squarcialupi Codex, the largest source of Italian music of the 14th century, contains 37 pieces by Bartolino. A few other sources contain pieces by him, and his music was evidently widespread, indicating his reputation.

Bartolino’s music, unlike that of his contemporary Francesco Landini, shows little influence from the French ars nova. His 27 ballate are almost all vocal duets, in the Italian fashion (the French at that time were mainly writing them as a single vocal line with one or two instrumental accompanying parts). Eleven of Bartolino’s madrigals survive; like the ballate, they are mostly for two voices, however there are two pieces for three, and one of them (La Fiera Testa) has a macaronic text which is trilingual, one strophe in Italian, one in Latin and the final Ritornello section in French. This practice was common in the High Middle Ages but had become rare by the end of the 14th century.

Magister Franciscus (fl. 1370–80) was a French composer-poet in the ars nova style of late medieval music. He is known for two surviving works, the three-part ballades: De Narcissus and Phiton, Phiton, beste tres venimeuse; the former was widely distributed in his lifetime. Modern scholarship disagrees on whether Franciscus was the same person as the composer F. Andrieu.

Philippus de Caserta (fl. c. 1370) was a late medieval music theorist and composer associated with the style known as ars subtilior. Most of his surviving works are ballades, although a Credo was recently discovered, and a rondeau has been attributed to him. His ballade En attendant souffrir was written for Bernabò Visconti, confirmed by the presence of Visconti’s motto in the upper voice. Two of Caserta’s pieces, En remirant and De ma dolour, use fragments of text from chansons by the most famous composer of the century, Guillaume de Machaut. Caserta’s own repute was significant enough for Johannes Ciconia to borrow portions of Caserta’s ballades for his own virelai, Sus une fontayne. Five theoretical treatises have been attributed to Caserta, with some in dispute among scholars.

Gherardello da Firenze (c. 1320–1325 – 1362 or 1363) was an Italian composer of the Trecento. He was one of the first composers of the period sometimes known as the Italian ars nova.

Although Gherardello was renowned during his time for his sacred music, little of it has survived. A Gloria and an Agnus Dei, both by Gherardello, are among just a handful of mass movements by Italian composers from before 1400. The style of Gherardello’s mass movements is similar to that of the madrigal, although more restrained emotionally: they are for two voices, which sing together most of the time, with occasional passages where they sing in alternation.

Gherardello’s secular music has survived in greater abundance. Ten madrigals, all for two voices; five ballatas, all for a single voice; and a very famous caccia, Tosto che l’alba, which is for three voices, survive. Stylistically his music is typical of the early Trecento, with the voices usually singing the same words at the same time, except for the caccia, in which the upper two voices sing a quickly moving canon, and the lowest voice sings a freely composed part in longer notes.

Most of Gherardello’s music has been preserved in the 15th century Squarcialupi Codex, although several other manuscripts, all from Tuscany, contain works of his. A portrait on the pages of the Codex devoted to his music is most likely him (each composer in that illuminated manuscript is pictured).

Francesco Landini (c. 1325 or 1335 – 2 September 1397) was an Italian composer, poet, organist, singer and instrument maker who was a central figure of the Trecento style in late medieval music. One of the most revered composers of the second half of the 14th century, he was by far the most famous composer in Italy.

Landini was the foremost exponent of the Italian Trecento style. His output was almost exclusively secular. While there are records that he composed sacred music, none of it has survived. What have survived are eighty-nine ballate for two voices, forty-two ballate for three voices, and another nine which exist in both two and three-voice versions. In addition to the ballate, a smaller number of madrigals have survived. Landini is assumed to have written his own texts for many of his works. His output, preserved most completely in the Squarcialupi Codex, represents almost a quarter of all surviving 14th-century Italian music.

- Chosi penoso

- Nella partita

- Adiu, adiu dous dame yolie

- Che cosa e questa, amor

- Creata fusti o vergine Maria

Lorenzo Masi, known as Lorenzo da Firenze (Magister Laurentius de Florentia; died December 1372 or January 1373), was an Italian composer and music teacher of the Trecento. He was closely associated with Francesco Landini in Florence, and was one of the composers of the period known as the Italian ars nova.

His style is progressive, sometimes experimental, but curiously conservative in other ways. While he used imitation, a relatively new musical technique, and heterophonic texture, one of the rarest textures in European music, he also still used parallel perfect intervals. Voice crossings are common, when he wrote for more than one voice (most of his music is monophonic). In addition he used chromaticism to a degree rare in the 14th century, at least prior to the activity of the composers of the ars subtilior.

French classical music influence is evident in some of his music, for example isorhythmic passages (characteristic of Machaut, but rare in Italian music). Some of the notational quirks in his work also suggest a connection with France.

The Monk of Salzburg (German: Mönch von Salzburg) was a German composer of the late 14th century. He worked at the court of the Salzburg archbishop Pilgrim von Puchheim (1365–96). More than 100 Liederhandschriften (manuscripts) in Early New High German are attributed to him.

His name and monastic order is unknown; some of the introductions to the manuscript sources mention the names Herman, Johans, and Hanns and describe him as either Benedictine or Dominican. Despite this confusion, all the manuscripts that contain his works “agree that he was a learned monk who wrote sacred and secular songs”. His compositions overcome the Minnesang traditions and even approach recent polyphonic settings.

Johannes Alanus (fl. late 14th or early 15th century) was an English composer. He wrote the motet Sub arturo plebs/Fons citharizancium/In omnem terram. Also attributed to him are the songs “Min frow, min frow” and “Min herze wil all zit frowen pflegen”, both lieds, and “S’en vos por moy pitié ne truis”, a virelai. O amicus/Precursoris, attributed simply to “Johannes”, may be the work of the same composer.

Sub Arturo plebs/Fons citharizancium/In omnem terram is an ars nova mensuration motet with a different text in each voice. The “triplum”, or third voice, is on a text which names 14 musicians. These mentions, in some cases, are the sole extant references to these active musicians. Brian Trowell has identified many of those named with royal households. There has been significant debate as to the dating of this motet. The earliest dating assumes that it was written for the 1349 founding of the Order of the Garter, this date suggested by Trowell. Roger Bowers suggests that the list of musicians includes musicians who were no longer active at the time of the writing. Margaret Bent and others argue for a later date because of the style of the music itself, which includes a complex structure with three levels of diminution and rhythmic overlapping. This later dating, however, does not fall in with the theory that the composer is the same as the chaplain Johannes Aleyn. A certain date earlier than 1370 for this work would lead to a change in accepted ideas about the mid-14th-century style.

Johannes Symonis Hasprois (fl. 1378–1428) was a French composer originally from Arras. Four of his works of music survive in four different manuscripts. Hasprois’s early two-voice ballade Puisque je sui fumeux is a prime example of the exceedingly complex style of the ars subtilior. The text of this ballade is also preserved anonymously as Balade de maistre fumeux. It is similar to a rondeau by Solage, Fumeux fume par fumee, and both were probably written for the highly eccentric circle gathered around Jean Fumée If so, then it probably dates to the time when Hasprois was at the court of Charles V.

Hasprois wrote two other ballades in the tradition of courtly love as it was being expressed circa 1400. Ma doulce amour is preserved in three manuscripts and is the more complicated of the two. The syllabic Se mes deux yeux is found in only one manuscript, alongside Ma doulce.

Jo[hannes] Susay or Jehan Suzay (sometimes written Suzoy or Susoy) (fl. c. 1380; d. after 1411) was a French composer of the Middle Ages. He is the composer of three ballades in the ars subtilior style, all found in the Chantilly Codex: A l’albre sec, Prophilias, un des nobles, and Pictagoras, Jabol et Orpheus. The last ballade is also found in the Boverio Codex, Turin T.III.2, with the more accurate incipit “Pytagoras, Jobal, et Orpheus” . A a three-voice Gloria “in fauxbourdon-like style” found in the Apt codex (ff. 25v/26r) is also attributed to Susay.

Susay’s secular works have been edited in Willi Apel, French Secular Music of the Fourteenth Century and Gordon Greene, Polyphonic Music of the Fourteenth Century, volumes 18 and 19, and his Gloria by Stäblein-Harder and Cattin/Facchin.

According to the anonymous, early-fifteenth century treatise, Règles de la seconde rhétorique, the poet Jehan de Suzay (named along with Tapissier and others) was still alive at the time of writing. He is generally supposed to be this composer.

Trebor was a 14th-century composer of polyphonic chansons, active in Navarre and other southwest European courts c. 1380–1400. He may be the same person also called Triboll, Trebol, and Borlet in other contemporaneous sources. His name is possibly an anadrome of Robert.

His compositions are associated with the style known as ars subtilior, and six of his works survive in one of the most important surviving manuscripts of ars subtilior music, the Chantilly Codex. Some of his pieces explicitly reference historical events such as the Aragonese conquest of Sardinia in 1388-89 and the reign of Gaston Febus, the count of Foix. His music was well known to Avignonese composers of the time, such as Grimace and F. Andrieu, who quoted some of his pieces in their works. He is noted for his use of displacement syncopation and sustained chords, the former of which is one of the hallmark devices of ars subtilior.

Jan z Jenštejna (1348 – 17 June 1400) was a Bohemian archbishop, composer and poet. From 1379 to 1396 he was the Archbishop of Prague. He studied in Bologna, Padova, Montpellier and Paris.

His musical works were compiled in the book Die Hymnen Johanns von Jenstein, Erzbischofs von Prag of Q. M. Dreves. His musical activity was not systematic, but rather random. Before 1380 it was often dance music, then religious music.

Martinus Fabri (died May 1400) was a North Netherlandish composer of the late 14th century. Of his compositions, only four complete pieces survive, all ballades. Two of these have French texts (Or se depart and N’ay je cause d’estre lies et joyeux) and are in the ars subtilior style, highly complex and mannered. Both are three-voice compositions, though there are two (incompatible) alternatives for the third voice in Or se depart—a triplum and a contratenor. The other two ballades are in Dutch (Eer ende lof heb d’aventuer and Een cleyn parabel), with a simpler syllabic style of setting. The Leiden manuscript in which all of Fabri’s works are found also contains an incomplete ballade, Een cleyn parabel, the text of which describes a dilemma: the poet loves his lady and would like to marry her, but finds it difficult to accept her recently born child. This may be an autobiographical reference: Martinus Fabri had a son baptized in April 1396, and the godmother was Margaret of Cleves, Countess of Holland.

Andreas de Florentia (also known as Andrea da Firenze, Andrea de’ Servi, Andrea degli Organi and Andrea di Giovanni; died 1415) was a Florentine composer and organist of the late medieval era. Along with Francesco Landini and Paolo da Firenze, he was a leading representative of the Italian ars nova style of the Trecento, and was a prolific composer of secular songs, principally ballate.

All of Andreas’s surviving music with reliable attribution is in the genre of the ballata. Thirty are known, with eighteen being for two voices and twelve for three; in addition, one ballade in French may be his work, based on stylistic similarities and a contemporary attribution of it to a name similar to his. The main source for his work is the Squarcialupi Codex, which also includes, in the section containing Andreas’s music, a colorful illustration of a man playing an organ, probably Andreas himself.

The two-voice ballate are usually for two singing voices; two of them include an instrumental tenor. Not all of the three-voice ballate have text in all three voices, and the third voice sometimes may have been played on an instrument.

Compared to Landini’s music, in which refinement, elegance, and a memorable melodic line were the clear goals of the composer, Andreas’s music is dramatic, restless, and sometimes disjunct, and includes sharp dissonances to highlight certain passages in the text. One of his ballate includes a melodic leap of an augmented octave, highlighting the word maledetto (accursed), causing it to leap out from the rest of the music.

Johannes de Porta (c. 1350?) is associated with one work in the Chantilly Codex, the four-voice Isorhythmic motet Alma polis religio/Axe poli cum artica. This is one of the last motets found in the Chantilly Codex and contains the names of several poets and composers presumably belonging to the Augustan order; de Porta identifies himself as “the composer.” The text is a difficult one to interpret, and sometimes this piece has been accredited to Egidius de Aurolia (Gilles of Orleans) as the text states that “from him, all melody flows.” Just who is precisely meant of the many Aegidiuses or Egidiuses known from fourteenth century France is unclear, and as the otherwise unknown de Porta appears to have signed the work internally, there remains little doubt that, whoever he was, he was the actual writer of Alma polis religio/Axe poli cum artica. For a work composed in the fourteenth century, it demonstrates uncommon skill and is in advance of its time.

- Alma polis religio/Axe poli cum artica

Anonymous

- Patrie pacis/Patria gaudentium (late 14th century – England)

Paolo da Firenze (Paolo Tenorista, Magister Dominus Paulas Abbas de Florentia) (c. 1355 – after September 20, 1436) was an Italian composer and music theorist of the late 14th and early 15th centuries. More surviving music of the Trecento is attributable to Paolo than to any other composer except for Francesco Landini. His music had both progressive and conservative aspects. While most of his surviving music is secular, and all of it vocal, two sacred compositions (a Benedicamus Domino for two voices, and a Gaudeamus omnes in Domino for three) have also survived.

His secular compositions are of three types: thirteen madrigals, forty-six ballate (some of which are fragmentary, and others of which have the ascription to Paolo erased in the source), and five miscellaneous secular songs. All of his music is for two or three voices, and all is datable through sources or stylistic features to the period before 1410. Whether he did any composing after 1410 is not known.

Paolo’s madrigals combine Italian and French notation, and show considerable influence of the Avignon mannerist school of the ars subtilior in their complex and intricate rhythmic patterns; however most of them are for only two voices, a conservative choice. The ballate are more progressively done overall; most are for three voices, and are lyrical, melodic, but yet use some of the extreme rhythmic intricacies of the ars subtilior school. The influence of Landini, hard to avoid for any Florentine composer late in the 14th century, is evident both in the madrigals and the ballate.

- Altro che sospirar (Ballate)

- Benedicamus domino

- Era Venus

Grazioso da Padova or Gratiosus de Padua (fl. 1391–1407) was an Italian composer of the late medieval and early Renaissance eras. Of his output only three fragments remain, two sacred and one secular. He wrote two three-voice settings of portions of the Mass, a Gloria and a Sanctus, as well as ballata (Alta regina de virtute ornata). Stylistic characteristics – a mix of French and Italian traits – indicate he may have been acquainted with Johannes Ciconia, a northerner who spent some time in Padua during the period when Grazioso was active there.

Giovanni Mazzuoli (also Giovanni degli Organi) (ca. 1360 – 14 May 1426) was an Italian composer and organist of the late medieval and early Renaissance eras.

Mazzuoli is best remembered for the absence, rather than the presence, of his musical compositions. There is a large section of the Squarcialupi Codex, an important source of early Italian music, which is marked out under his name. However, no music is written in these pages; they are decorated around the edges but left blank otherwise. There are at least ten of his works written on a palimpsest in an Italian manuscript, Florence, Archive of San Lorenzo, MS 2211, but the state of the parchment has until recently left them essentially unreadable. Nine of his son Piero’s works are found in this manuscript as well. Nino Pirrotta attributed two works to Mazzuoli, one of which is a ballata ascribed in a manuscript to “Gian Toscan”, and the other a piece in the Roquefort Codex ascribed to “Johannes Florentius”. The latter has since been shown not to be a work of Giovanni Mazzuoli.

Johannes Cuvelier (fl c. 1372–d. after 1387) was a composer of the ars subtilior, whose surviving works are preserved in the Chantilly Codex. He was possibly born in Tournai and worked at the court of Charles V.

His most important work is the poem La Chanson de Bertrand du Guesclin, a tribute to the Breton military commander Bertrand du Guesclin. He also has four works in the Chantilly Codex:

- Se Galaas et le puissant Artus

- Onques Arthur, Alixandre et Paris

- Se Genevre, Tristan, Yssout, Helaine

- En la saison que toute riens encline

Grimace (fl. mid-to-late 14th century; French; also Grymace, Grimache or Magister Grimache) was a French composer-poet in the ars nova style of late medieval music. Virtually nothing is known about Grimace’s life other than speculative information based on the circumstances and content of his five surviving compositions of formes fixes; three ballades, a virelai and rondeau. His best known and most often performed work in modern-times is the virelai and proto-battaglia: A l’arme A l’arme.

He is thought to have been a younger contemporary of Guillaume de Machaut and based in southern France. Three of his works were included in the Chantilly Codex, which is an important source of ars subtilior music. However, along with P. des Molins, Jehan Vaillant and F. Andrieu, Grimace was one of the post-Machaut generation whose music shows few distinctly ars subtilior features, leading scholars to recognize Grimace’s work as closer to the ars nova style of Machaut.

- Se Zephirus/Se Jupiter

Antonello da Caserta, also Anthonello de Casetta, Antonellus Marot, was an Italian composer of the medieval era, active in the late 14th and early 15th centuries. He is one of the more renowned composers of the generation after Guillaume de Machaut. Antonello set texts in both French and Italian, including Beauté parfaite of Machaut; this is the only surviving musical setting of a poem by Machaut which is not by Machaut himself. He was highly influenced by French musical models, one of the first Italians to be so. One of his ballades quotes Jehan Vaillant, a composer active in Paris. He also made use of irregular mensuration signs, found in few other manuscripts. He also uses proportional rhythms in some ballades, a device which became more popular in later periods. His Italian works tend to be simpler, especially the ballate. Both his French and Italian works take as their subjects courtly love.

Solage (fl. late 14th century), possibly Jean So(u)lage, was a French composer, and probably also a poet. He composed the most pieces in the Chantilly Codex, the principal source of music of the ars subtilior, the manneristic compositional school centered on Avignon at the end of the century. Stylistically, Solage’s works exhibit two distinctly different characters: a relatively simple one usually associated with his great predecessor and elder contemporary Guillaume de Machaut, and a more recherché one, complex in the areas of both pitch and rhythm, characteristic of the ars subtilior (“more subtle art”). These two styles mostly exist separately in different songs but sometimes are found mixed in a single composition, where they can be used to underscore the musical and poetic structure. In his simpler “Machaut” style pieces Solage nevertheless makes many personal choices that are very different from what Machaut typically does. Moreover, the simpler style is not necessarily an indication of an earlier date nor the complex style a reliable sign of a later date. Solage uses his techniques to link text and music together, either in terms of form or else of meaning. Nevertheless, some of his ars subtilior music was quite experimental: the best-known example in this complex style is his bizarre Fumeux fume par fumée (approx: “The smoky one smokes through [or for] smoke”), which is extravagantly chromatic for the time; it also contains some of the lowest tessitura vocal writing in any music of the period.

Jacob Senleches (fl. 1382/1383 – 1395) (also Jacob de Senlechos [i.e. Senleches] and Jacopinus Senlesses) was a Franco-Flemish composer and harpist of the late Middle Ages. He composed in a style commonly known as the ars subtilior.

Despite the small number of transmitted compositions, Jacob de Senleches is counted among the central personalities of ars subtilior. All his compositions are polyphonic settings of French texts for three parts. Some texts appear autobiographical while others participate in a widespread tradition of textual and musical citation. Senleches developed many distinctive rhythmic and notational innovations.

Borlet was a 14th- and 15th-century composer whose life we know extremely little about. It is thought that his name is an anagram of Trebol, a French composer who served Martin of Aragon in 1409 at the same time as Gacian Reyneau and other composers in the Codex Chantilly.

If this Trebol is the same as Trebor then he has seven surviving compositions. If not then he is only known for his virelai He tres doulz roussignol and its variation Ma tre dol rosignol, which is also a virelai.

John Forest (c. 1365 – 25 March 1446), was an English composer of the late medieval era. There are two motets of Forest’s in the Old Hall Manuscript, but much more survives in Continental sources such as the Trent Codices. His music contrasts declamatory and melismatic passages; the conflict of rhythms between the various voices gives his music a restless quality.

- Qualis est dilectus tuus

Johannes Ciconia (c. 1370 – between 10 June and 13 July 1412) was an important Franco-Flemish composer and music theorist of trecento music during the late medieval era. He was born in Liège, but worked most of his adult life in Italy, particularly in the service of the papal chapels in Rome and later and most importantly at Padua Cathedral.

Ciconia’s music is an eclectic blend of styles. Pieces typical of northern Italy, such as his madrigal Una panthera, appear with pieces steeped in the French ars nova. The more complex ars subtilior style surfaces in Sus un fontayne. While it remains late medieval in style, his writing increasingly points toward the melodic patterning of the Renaissance, for instance in his setting of O rosa bella. He wrote music both secular (French virelais, Italian ballate and madrigals) and sacred (motets and Mass movements, some of them isorhythmic) in form. He is also the author of two treatises on music, Nova Musica and De Proportionibus (which expands on some ideas in Nova Musica). His theoretical ideas stem from the more conservative Marchettian tradition in contrast to those of his Paduan contemporary Prosdocimus de Beldemandis.

- Venecie mundi splendor – Michael qui stena domus – Italie

- VI. Gloria spiritus et alme No. 6

- XV. Albane, misse celitus – Albane doctor maxime

Aleyn (fl. c. 1400) was an English composer. Two of his works survive in the Old Hall Manuscript, one a Gloria (no. 8), the other a Sarum Agnus Dei discant (no. 3, Old Hall, no. 128), later scratched out, which is ascribed to W. Aleyn.

Egardus (fl. 1400; also Engardus or Johannes Echgaerd) was a European medieval composer of ars subtilior. Almost no information survives about his life, and only three of his works are known. A certain “Johannes Ecghaerd”, who held chaplaincies in Bruges and Diksmuide, may be a possible match for Egardus. The extant works—a canon and two Glorias—appear to be less complex than music by mid-century composers, possibly because they date from either very early or very late in Egardus’ career.

Queldryk (also Qweldryk) (fl. c. 1400) was an English composer. He is thought to have been associated with a similarly named estate (Wheldrake) of the Cistercian monastery of Fountains Abbey in Yorkshire. He may have been the Richard Queldryk who donated a miscellanea volume of sacred music to Lichfield Cathedral. His known surviving output comprises two pieces in the Old Hall Manuscript, a Gloria and a Credo.

Andrea Stefani (fl. c. 1400) was an Italian monk and a member of the Order of the Bianchi Gesuati, literally meaning “white Jesuits,” but not related to the Jesuit monks who are generally known today. He is known to have led his order in public processions in Florence in 1399 and was considered a master singer and composer. By 1406 Stefani had settled in Lucca and his three surviving musical works are found only in the Lucca Codex or “Codex Mancini” (Archivio di Stato 184.) Stefani is known for two ballate, Con tutta gentilezza and I senti’ matutino, and a madrigal, Morte m’a sciolt. Five lauds written by Stefani are also known to exist, but as texts only, with no music. As Stefani’s music is located in the part of the Mancini Codex that was compiled in Lucca, his works were probably added to the book between 1410 and 1430.

Oswald von Wolkenstein (1376 or 1377–August 2, 1445) was a poet, composer and diplomat. He is one of the most important German composers of the Middle Ages. There are three main topics of his work: travel, God and sex. Oswald’s poems are preserved in three manuscripts:

- MS A (Vienna), 42 songs completed in 1425, with an addition of another 66 poems from 1427 to 1436.

- MS B (Innsbruck): 1432

- MS C (Innsbruck-Trostburg): 1450, a copy of B.

Thomas Fabri (c. 1380 – c. 1420) was a composer from the Southern Netherlands (Flanders), who worked during the early 15th century. Only four of his works have been preserved in foreign sources. Two works are settings in three parts on Dutch lyrics. They may have been written down by a German in a song book (perhaps at the Council of Constance) that has been illustrated by an Italian and is kept now in the Abbey of Heiligenkreuz.

Matteo da Perugia (fl. 1400–1416) was a medieval Italian composer, presumably from Perugia. From 1402 to 1407 he was the first magister cappellae of the Milan Cathedral; his duties included being cantor and teaching three boys selected by the Cathedral deputies. He wrote many contra-tenors to existing works, which resulted in many of these being wrongly ascribed to him. Matteo wrote in many forms, including the virelai, the ballade, and the rondeau.

Baude Cordier (fl. early 15th century) was a French composer in the ars subtilior style of late medieval music. Cordier’s works are considered among the prime examples of ars subtilior. In line with that cultural trend, he was fond of using red note notation, also known as coloration, a technique stemming from the general practice of mensural notation. The change in color adjusts the rhythm of a particular note from its usual form. (This musical style and type of notation has also been termed “mannerism” and “mannered notation.”)

- Se Cuer D’amant Par Soy Humilier

Transitioning to the Renaissance

Demarcating the end of the medieval era and the beginning of the Renaissance era, with regard to the composition of music, is difficult. While the music of the fourteenth century is fairly obviously medieval in conception, the music of the early fifteenth century is often conceived as belonging to a transitional period, not only retaining some of the ideals of the end of the Middle Ages (such as a type of polyphonic writing in which the parts differ widely from each other in character, as each has its specific textural function), but also showing some of the characteristic traits of the Renaissance (such as the increasingly international style developing through the diffusion of Franco-Flemish musicians throughout Europe, and in terms of texture an increasing equality of parts). Music historians do not agree on when the Renaissance era began, but most historians agree that England was still a medieval society in the early fifteenth century. While there is no consensus, 1400 is a useful marker, because it was around that time that the Renaissance came into full swing in Italy.

Polyphony, in use since the 12th century, became increasingly elaborate with highly independent voices throughout the 14th century. With John Dunstaple and other English composers, partly through the local technique of faburden (an improvisatory process in which a chant melody and a written part predominantly in parallel sixths above it are ornamented by one sung in perfect fourths below the latter, and which later took hold on the continent as “fauxbordon”), the interval of the third emerges as an important musical development; because of this Contenance Angloise English composers’ music is often regarded as the first to sound less truly bizarre to 2000s-era audiences who are not trained in music history.

English stylistic tendencies in this regard had come to fruition and began to influence continental composers as early as the 1420s, as can be seen in works of the young Guillaume Du Fay, among others. While the Hundred Years’ War continued, English nobles, armies, their chapels and retinues, and therefore some of their composers, travelled in France and performed their music there; it must also of course be remembered that the English controlled portions of northern France at this time.

Late Medieval vs. Early Renaissance: Quick Comparison Table

| Feature | Late Medieval Style | Early Renaissance Style |

|---|---|---|