Your cart is currently empty!

A History of Western Art Music

Chapter Four: The Late Renaissance

In Venice, from about 1530 until around 1600, a period known as the Late Renaissance, an impressive polychoral style developed, which gave Europe some of the grandest, most sonorous music composed up until that time, with multiple choirs of singers, brass and strings in different spatial locations in the Basilica San Marco di Venezia (see Venetian School). These multiple revolutions spread over Europe in the next several decades, beginning in Germany and then moving to Spain, France, and England somewhat later, demarcating the beginning of what we now know as the Baroque musical era.

The Roman School was a group of composers of predominantly church music in Rome, spanning the late Renaissance and early Baroque eras. Many of the composers had a direct connection to the Vatican and the papal chapel, though they worked at several churches; stylistically they are often contrasted with the Venetian School of composers, a concurrent movement which was much more progressive. By far the most famous composer of the Roman School is Giovanni Pierluigi da Palestrina. While best known as a prolific composer of masses and motets, he was also an important madrigalist. His ability to bring together the functional needs of the Catholic Church with the prevailing musical styles during the Counter-Reformation period gave him his enduring fame.

The brief but intense flowering of the musical madrigal in England, mostly from 1588 to 1627, along with the composers who produced them, is known as the English Madrigal School. The English madrigals were a cappella, predominantly light in style, and generally began as either copies or direct translations of Italian models. Most were for three to six voices.

Musica reservata is either a style or a performance practice in a cappella vocal music of the latter half of the 16th century, mainly in Italy and southern Germany, involving refinement, exclusivity, and intense emotional expression of sung text.

In addition, writers since 1932 have observed what they call a seconda prattica (an innovative practice involving monodic style and freedom in treatment of dissonance, both justified by the expressive setting of texts) during the late 16th and early 17th centuries.

The above playlist contains selected works by some of the composers covered in the remainder of this chapter. The numbers that appear before the names of compositions in the text below refer to their position in the playlist. There will be also separate playlists for each composer which contain all of the recordings available on Spotify barring those that are arrangements for modern instruments, instrumental arrangements of pieces originally scored for voices and the like.

Composers of the Late Renaissance

- Quand je bois du vin clairet (Tourdion) (Anon. First published in 1530 – France)

Mateo Flecha (1481–1553) was a Catalan composer born in Kingdom of Aragon, in the region of Prades. He is sometimes known as “El Viejo” (the elder) to distinguish him from his nephew, Mateo Flecha “El Joven” (the younger), also a composer of madrigals. Flecha is best known as composer of Las Ensaladas de Flecha, a work for four or five voices written for the diversion of courtiers in the palace published in Prague in 1581 by the same nephew. Las Ensaladas, frequently mixed languages: Spanish, Catalan, Italian, French, and Latin. In addition to Las Ensaladas, Flecha is known for his villancicos, a common poetic and musical form of the Iberian Peninsula and Latin America popular from the late 15th to 18th centuries.

- Las Ensaladas de Flecha: El Fuego

Clément Janequin (c. 1485 – 1558) was a French composer and one of the most famous composers of popular chansons of the entire Renaissance, who along with Claudin de Sermisy, was hugely influential in the development of the Parisian chanson, especially the programmatic type. The wide spread of his fame was made possible by the concurrent development of music printing. His career was highly unusual for his time, in that he never had a regular position with a cathedral or an aristocratic court. Instead he held a series of minor positions, often with important patronage. Few composers of the Renaissance were more popular in their lifetimes than Janequin. His chansons were well-loved and widely sung. The Paris printer Pierre Attaingnant printed five volumes with his chansons. La bataille, which vividly depicts the sounds and activity of a battle, is a perennial favorite of a cappella singing groups even in the present day.

- D’un seul soleil

Claudin de Sermisy (c. 1490 – 13 October 1562) along with Clément Janequin he was one of the most renowned composers of French chansons in the early 16th century; in addition he was a significant composer of sacred music. His music was both influential on, and influenced by, contemporary Italian styles.

Sermisy wrote both sacred music and secular music, and all of it is for voices. Of his sacred music, 12 complete masses have survived, including a Requiem mass, as well as approximately 100 motets, some magnificats and a set of Lamentations. His interest in the sacred genres increased steadily throughout his life, corresponding to a decline in interest in secular forms, using the publication dates as a guide (actual dates of compositions are extremely difficult to establish for composers of this period, unless a work happened to be composed for a specific occasion). Since the prevailing style of polyphony among contemporary composers during his late career was dense, seamless, with pervasive imitation, as typified in the music of Jean Mouton and Nicolas Gombert, it is significant that he tended to avoid this style, preferring clearer textures and short phrases: a style more akin to the chansons he wrote earlier in his career. In addition he varied the texture in his composition by alternating polyphonic passages with homorhythmic, chordal ones, much like the texture found in his secular music.

Sermisy wrote two of the few polyphonic settings of the Passion found in French music of the period; the musical setting is simple, compared to his masses and motets, and he strove to make the words clearly understandable. The gospels chosen were those of St. Matthew and St. John. Sermisy’s settings were published in the 10th volume of Motets published by Pierre Attaignant.

By far Sermisy’s most famous contribution to music literature is his output of chansons, of which there are approximately 175. They are similar to those of Janequin, although less programmatic; his style in these works has also been described as more graceful and polished than that of the rival composer. Typically Sermisy’s chansons are chordal and syllabic, shunning the more ostentatious polyphony of composers from the Netherlands, striving for lightness and grace instead. Sermisy was fond of quick repeated notes, which give the texture an overall lightness and dance-like quality. Another stylistic trait seen in many of Sermisy’s chansons is an initial rhythmic figure consisting of long-short-short (minim-crotchet-crotchet, or half-quarter-quarter), a figure which was to become the defining characteristic of the canzona later in the century. The texts Sermisy chose were usually from contemporary poets, such as Clément Marot (he set more verse by Marot than any other composer). Typical topics were unrequited love, nature, and drinking. Several of his songs are on the topic of an unhappy young woman stuck with an unattractive and unvirile old man, a sentiment not unique to his age. Most of his chansons are for four voices, though he wrote some for three early in his career, before four-voice writing became the norm. Influence from the Italian frottola is evident, and Sermisy’s chansons themselves influenced Italian composers, since his music was reprinted numerous times both in France and in other parts of Europe.

- Tant que vivray

Adrian Willaert (c. 1490 – 7 December 1562) was a Flemish composer mainly active in Italy, and the founder of the Venetian School. He was one of the most representative members of the generation of northern composers who moved to Italy and transplanted the polyphonic Franco-Flemish style there. Willaert was one of the most versatile composers of the Renaissance, writing music in almost every extant style and form. In force of personality, and with his central position as maestro di cappella at St. Mark’s, he became the most influential musician in Europe between the death of Josquin and the time of Palestrina. According to Gioseffo Zarlino writing later in the 16th century, Willaert was the inventor of the antiphonal style from which the polychoral style of the Venetian school evolved. As there were two choir lofts – one to each side of the main altar of St. Mark’s, both provided with an organ —, Willaert divided the choral body into two sections, using them either antiphonally or simultaneously. De Rore, Zarlino, Andrea Gabrieli, Donato, and Croce, Willaert’s successors, all cultivated this style. The tradition of writing that Willaert established during his time at St. Mark’s was continued by other composers working there throughout the 17th century. He then composed and performed psalms and other works for two alternating choirs. This innovation met with instantaneous success and strongly influenced the development of the new method.

In Venice, a compositional style, established by Willaert, for multiple choirs dominated. In 1550 he published Salmi spezzati, antiphonal settings of the psalms, the first polychoral work of the Venetian school. Willaert’s work in the religious genre established Flemish techniques firmly as an important part of the Venetian Style. While more recent research has shown that Willaert was not the first to use this antiphonal, or polychoral method — Dominique Phinot had employed it before Willaert, and Johannes Martini even used it in the late 15th century – Willaert’s polychoral settings were the first to become famous and widely imitated.

With his contemporaries, Willaert developed the canzone (a form of polyphonic secular song) and ricercar, which were forerunners of modern instrumental forms. Willaert was among the first to extensively use chromaticism in the madrigal. Looking forward, we are given an image of early word painting in his madrigal Mentre che’l cor. Willaert, who was fond of the older compositional techniques such as the canon, often placed the melody in the tenor of his compositions, treating it as a cantus firmus. Willaert, with the help of De Rore, standardized a five-voice setting in madrigal composition. Willaert also pioneered a style that continued until the end of the madrigal period of reflecting the emotional qualities of the text and the meanings of important words as sharply and clearly as possible.

Willaert was no less distinguished as a teacher than as a composer. Among his disciples were Cipriano de Rore, his successor at St. Mark’s; Costanzo Porta; the Ferrarese Francesco Viola; Gioseffo Zarlino; and Andrea Gabrieli. Another composer stylistically descended from Willaert was Lassus. These composers, except for Lassus, formed the core of what came to be known as the Venetian school, which was decisively influential on the stylistic change that marked the beginning of the Baroque era. Among Willaert’s pupils in Venice, one of the most prominent was his fellow northerner Cipriano de Rore. The Venetian School flourished for the rest of the 16th century, and into the 17th, led by the Gabrielis and others. Willaert left a large number of compositions – 8 (or possibly 10) masses, over 50 hymns and psalms, over 150 motets, about 60 French chansons, over 70 Italian madrigals and 17 instrumentals (ricercars).

- Faulte d’argent (chanson for 6 voices)

- Le vecchie per invidia (canzona for 4 voices)

Cristóbal de Morales (c. 1500 – between 4 September and 7 October 1553) was a Spanish composer who is generally considered to be the most influential Spanish composer before Tomás Luis de Victoria. Morales was the first Spanish composer of international renown. His works were widely distributed in Europe, and many copies made the journey to the New World. Many music writers and theorists in the hundred years after his death considered his music to be among the most perfect of the time. Almost all of his music is sacred, and all of it is vocal, though instruments may have been used in an accompanying role in performance. He wrote many masses, some of spectacular difficulty, most likely written for the expert papal choir; he wrote over 100 motets; and he wrote 18 settings of the Magnificat, and at least five settings of the Lamentations of Jeremiah (one of which survives from a single manuscript in Mexico). The Magnificats alone set him apart from other composers of the time, and they are the portion of his work most often performed today. Stylistically, his music has much in common with other middle Renaissance work of the Iberian peninsula, for example a preference for harmony heard as functional by the modern ear (root motions of fourths or fifths being somewhat more common than in, for example, Gombert or Palestrina), and a free use of harmonic cross-relations rather like one hears in English music of the time, for example in Thomas Tallis.

Some unique characteristics of his style include the rhythmic freedom, such as his use of occasional three-against-four polyrhythms, and cross-rhythms where a voice sings in a rhythm following the text but ignoring the meter prevailing in other voices. Late in life he wrote in a sober, heavily homophonic style, but all through his life he was a careful craftsman who considered the expression and understandability of the text to be the highest artistic goal.

- Office de laudes: No. 6. Miserere

Anonymous

- Prelude (Pierre Attaingnant was a publisher, not a composer)

- Liber Primus Leviorum Carminum: Galliard d’escosse (Pierre Phalèse was a publisher, not a composer)

Thomas Tallis (c. 1505 – 23 November 1585) was an English composer considered one of England’s greatest composers and is honored for his original voice in English musicianship. His compositions are primarily vocal, and he occupies a primary place in anthologies of English choral music. The earliest surviving works by Tallis are Ave Dei patris filia, Magnificat for four voices, and two devotional antiphons to the Virgin Mary, Salve intemerata virgo and Ave rosa sine spinis, which were sung in the evening after the last service of the day; they were cultivated in England at least until the early 1540s.

Henry VIII’s break from the Roman Catholic Church in 1534 and the rise of Thomas Cranmer noticeably influenced the style of music being written. Cranmer recommended a syllabic style of music where each syllable is sung to one pitch, as his instructions make clear for the setting of the 1544 English Litany. As a result, the writing of Tallis and his contemporaries became less florid. Tallis’ Mass for Four Voices is marked with a syllabic and chordal style emphasizing chords, and a diminished use of melisma. He provides a rhythmic variety and differentiation of moods depending on the meaning of his texts. Tallis’ early works also suggest the influence of John Taverner and Robert Fayrfax. Taverner in particular is quoted in Salve intemerata virgo, and his later work, Dum transisset sabbatum.

The reformed Anglican liturgy was inaugurated during the short reign of Edward VI (1547–53), and Tallis was one of the first church musicians to write anthems set to English words, although Latin continued to be used alongside the vernacular. Queen Mary set about undoing some of the religious reforms of the preceding decades, following her accession in 1553. She restored the Sarum Rite, and compositional style reverted to the elaborate writing prevalent early in the century. Two of Tallis’s major works were Gaude gloriosa Dei Mater and the Christmas Mass Puer natus est nobis, and both are believed to be from this period.

Some of Tallis’s works were compiled by Thomas Mulliner in a manuscript copybook called The Mulliner Book before Queen Elizabeth’s reign, and may have been used by the queen herself when she was younger. Elizabeth succeeded her half-sister in 1558, and the Act of Uniformity abolished the Roman Liturgy and firmly established the Book of Common Prayer. Composers resumed writing English anthems, although the practice continued of setting Latin texts among composers employed by Elizabeth’s Chapel Royal. The religious authorities at the beginning of Elizabeth’s reign, being Protestant, tended to discourage polyphony in church unless the words were clearly audible or, as the 1559 Injunctions stated, “playnelye understanded, as if it were read without singing”. The Injunctions, however, also allowed a more elaborate piece of music to be sung in church at certain times of the day, and many of Tallis’s more complex Elizabethan anthems may have been sung in this context, or alternatively by the many families that sang sacred polyphony at home.

Tallis wrote nine psalm chant tunes for four voices for Archbishop Matthew Parker’s Psalter published in 1567. One of the nine tunes was the “Third Mode Melody” which inspired the composition of Fantasia on a Theme by Thomas Tallis by Ralph Vaughan Williams in 1910. His setting of Psalm 67 became known as “Tallis’s Canon”, and the setting by Thomas Ravenscroft is an adaptation for the hymn “All praise to thee, my God, this night” (1709) by Thomas Ken, and it has become his best-known composition.

Tallis’s better-known works from the Elizabethan years include his settings of the Lamentations (of Jeremiah the Prophet) for the Holy Week services and the unique motet Spem in alium written for eight five-voice choirs, for which he is most remembered. He also produced compositions for other monarchs, and several of his anthems written in Edward’s reign are judged to be on the same level as his Elizabethan works, such as “If Ye Love Me”. Records are incomplete on his works from previous periods; 11 of his 18 Latin-texted pieces from Elizabeth’s reign were published, “which ensured their survival in a way not available to the earlier material”. Toward the end of his life, Tallis resisted the musical development seen in his younger contemporaries such as Byrd, who embraced compositional complexity and adopted texts of disparate biblical extracts. Tallis was content to draw his texts from the Liturgy and wrote for the worship services in the Chapel Royal. He composed during the conflict between Catholicism and Protestantism, and his music often displays characteristics of the turmoil.

- Archbishop Parker’s Psalter – Third Tune: “Why Fum’th in Sight” (published 1567)

- Thou Wast, O God, and Thou Wast Blest (same as the above tune but set to words by John Mason (1646?–1694).

- Spem in alium (first performed in 1570 0r 1571)

- Jesu, Salvatore saeculi

- Magnificat (Dorian)

- O sacrum convivium

Melchor Robledo, also Melcior y Robredo (c . 1510 – November 23, 1586) was a Spanish musician and composer. He is considered the initiator of the Aragonese school of polyphonic music of the 16th century. Among his works, almost all religious and in Latin, five masses, eight motets, three invitations and several Te Deum, psalms, magnificats and hymns for vespers have been preserved. Thematic motifs are often taken from Gregorian chant.

- Salve Regina: I. Salve Regina

Jacobus Clemens non Papa (also Jacques Clément) (c. 1510 to 1515 – 1555 or 1556) was a Netherlandish composer based for most of his life in Flanders. He was a prolific composer in many of the current styles, and was especially famous for his polyphonic settings of the psalms in Dutch known as the Souterliedekens. Unlike many of his contemporaries, Clemens seems never to have traveled to Italy, with the result that Italian influence is absent in his music. He represents the northern European dialect of the Franco-Flemish style. Clemens was one of the chief representatives of the generation between Josquin and Palestrina and Orlandus Lassus. He was primarily a composer of sacred music. In fact, his musical output was roughly 80 percent sacred music, either liturgical or for private use. Of his approximately 233 motets, only three contain secular texts, in the form of hymns of praise of music. However, he did compose just above 100 secular works that encompass the whole gamut of poetic genres that were used by composers in his generation. Considering that his career as a composer lasted for barely two decades, Clemens was an extremely prolific composer.

Of all his works, the Souterliedekens were perhaps the most widely known and influential. The Souterliedekens were published in 1556-1557 by Susato in his Musyck Boexken (“Music Books”), IV-VII and comprised the only Protestant part-music in Dutch during the Renaissance. Based on a preceding volume of Souterliedekens printed by Symon Cock that contained monophonic settings of the psalms in Dutch, Clemens’s Souterliedekens became the first complete polyphonic setting of all 150 psalms in Dutch. Presumably, the original verse translation of the Psalter into the Dutch language was completed by Willem van Nievelt from Wittenberg. Clemens’s part-settings are generally simple, and designed to be sung by people at home. They use the well-known secular tunes that were printed in the Cock edition, including drinking songs, love songs, ballads, and other popular songs of the time, as a cantus firmus. Most of them were set for 3 parts, and there are 26 different combinations of these voices. Some of the Souterliedekens are based on dance-songs and are frankly homophonic and homorhythmic, while others use imitation. It is notable that these pieces of music survived the ban in 1569 when the government under the Duke of Alba censured all books that were deemed heretical.

After Clemens’s death, his works were distributed to Germany, France, Spain, and even among various circles in England. The influence of Clemens was especially prominent in Germany. Franco-Flemish composer Lassus in particular knew his music well and incorporated elements of his style.

- Je prends en gre & morir m’y fault à 4 (chanson first published in 1539)

Tielman (or Tylman) Susato (c. 1510/15 – after 1570) was a composer, instrumentalist and publisher of music in Antwerp, Belgium. He wrote (and published) several books of masses and motets which are in the typical imitative polyphonic style of the time. He also wrote two books of chansons which were specifically designed to be sung by young, inexperienced singers: they are for only two or three voices. Most important of his publications in terms of distribution and influence were the Souterliedekens of Clemens non Papa, which were metrical psalm settings in Dutch, using the tunes of popular songs. They were hugely popular in the Netherlands in the 16th century. Susato also was a prolific composer of instrumental music, and much of it is still recorded and performed today. He produced one book of dance music in 1551, Het derde musyck boexken … alderhande danserye (La Danserye), composed of pieces in simple but artistic arrangement. Most of these pieces are dance forms (allemandes, galliards, and so forth).

- La Danserye: Ronde and Salterelie

- La Danserye: Allemaigne and Recoupe

- La Danserye: “Mille regretz”

- La Danserye: Le Pingue (Reprise)

- La Danserye: La Bataille

Pierre Certon (c. 1510–1520 – 23 February 1572) was a French composer representative of the generation after Josquin and Mouton, and was influential in the late development of the French chanson. Certon wrote eight masses that survive, motets, psalm settings, chansons spirituelle (chansons with religious texts, related to the Italian madrigali spirituali), and numerous secular chansons. His style is relatively typical of mid-century composers, except that he was unusually attentive to large-scale form, for example framing longer masses (such as his Requiem) with very simple movements, with the inner movements showing greater tension and complexity. In addition he was skilled at varying texture between homophonic and polyphonic passages, and often changing the number and register of voices singing at any time. His chanson settings were famous, and influential in assisting the transformation of the chanson from the previous light, dance-like, four-part texture to the late-century style of careful text setting, emotionalism, greater vocal range, and larger number of voices. Cross-influence with the contemporary Italian form of the madrigal was obvious, but chansons such as those by Certon retained a lightness and a rhythmic element characteristic of the French language itself.

- O Madame, per-je mon tems

- De Profundis en faux-bourdon, Jean de Moulin

Anonymous

- Laroque Gaillarde

- Alemande de Liege

Jean Guyot (Châtelet, Belgium, 1512 – 1588) was a Franco-Flemish composer of the late Renaissance. He was highly regarded by his contemporaries, including Hermann Finck. In addition to music (chansons, motets, a Te Deum), he also published a poetical work.

- En lieux d’esbatz m’assault melancolie (1550)

- Vous perdez temps de me dire mal d’elle (1550)

Claude Goudimel (c. 1514 to 1520 – between 28 August and 31 August 1572) was a French composer, music editor and publisher, and music theorist. Goudimel is most famous for his four-part settings of the psalms of the Genevan Psalter, in the French versions of Clément Marot. In one of his four complete editions he puts – unlike other settings at the time – the melody in the topmost voice, the method which has prevailed in hymnody to the present day. In addition he composed masses, motets, and a considerable body of secular chansons, almost all of which date from before his conversion to Protestantism (probably around 1560).

In 1554, he became the editor of a large collection of masses, motets and Magnificat of several composers, a collection printed by Nicolas Duchemin, and in which Goudimel appeared as the author of seven Latin and Catholic works. In the year following, Goudimel, still at Duchemin’s, brought out a book of pieces for four voices of his composition on the Odes of Horace. In 1566, he published his seventh book of psalms in the form of motets. It was, therefore, after his departure from Paris that the celebrities Adrien le Roy and Robert Ballard published his masses in 1558; and it was also during his time in Metz that Goudimel began to concentrate all of his artistic ability in the various musical interpretations of the French translation of the psalms by Clément Marot and Théodore de Bèze. He worked on the continuation of his large collection of motet-shaped psalms, and wrote almost simultaneously two different versions of the complete psalter, each containing one hundred and fifty psalms.

Goudimel’s style tends to be homophonic, with an intriguing use of syncopated rhythm and melisma and staggered voice entries to bring out inner parts, especially in the chansons. His Psalm settings, however, are more polyphonic, characteristic of the moderate contrapuntal style exemplified by the chansons of Jacques Arcadelt, an approximate contemporary. His Opera Omnia extends to 14 volumes, though several of his works are fragmentary, missing one or more voices.

- Estans assis aux rives aquatiques

Cipriano de Rore (1515 or 1516 – between 11 and 20 September 1565) was a Franco-Flemish composer active in Italy. Not only was he a central representative of the generation of Franco-Flemish composers after Josquin des Prez who went to live and work in Italy, but he was one of the most prominent composers of madrigals in the middle of the 16th century. His experimental, chromatic, and highly expressive style had a decisive influence on the subsequent development of that secular music form. His 1542 book was an extraordinary event, and recognized as such at the time: it established five voices as the norm, rather than four, and it married the polyphonic texture of the Netherlandish motet with the Italian secular form, bringing a seriousness of tone which was to become one of the predominant trends in madrigal composition all the way into the seventeenth century. All of the lines of development in the madrigal in the late century can be traced to ideas first seen in Rore; according to Alfred Einstein, his only true spiritual successor was Claudio Monteverdi, another revolutionary.

While Rore is best known for his Italian madrigals, he was also a prolific composer of sacred music, both masses and motets. Josquin was his point of departure, and he developed many of his techniques from the older composer’s style. Rore’s first three masses are a response to the challenge of his heritage and to the music of his predecessor, Josquin. In addition to five masses, he wrote about 80 motets, many psalms, secular motets, and a setting of the St. John Passion.

It was as a composer of madrigals, however, that Rore achieved enduring fame. With his madrigals published primarily between 1542 and 1565, he was one of the most influential madrigalists at mid-century. His early madrigals reflect the styles of Willaert with the use of clear diction, thick and continuous counterpoint, and pervasive imitation. These works are mostly for four or five voices, with one for six and another for eight. The tone of his writing tends toward the serious, especially as contrasted with the light character of the work of his predecessors, such as Arcadelt and Verdelot. Rore chose not to write madrigals of frivolous nature, preferring to focus on serious subject matter, including the works of Petrarch, and tragedies presented at Ferrara. Rore carefully brought out the varying moods of the texts he set, developing musical devices for this purpose; additionally he often ignored the structure of the line, line division, and rhyme, deeming it unnecessary that the musical and poetic lines correspond.

In addition, Rore experimented with chromaticism, following some of the ideas of his contemporary Nicola Vicentino. He used all the resources of polyphony as they had developed by the middle 16th century in his work, including imitation and canonic techniques, all in the service of careful text setting. Rore also composed secular Latin motets, a relatively unusual “cross-over” form in the mid-16th century. These motets, being a secular variation of a normally sacred form, paralleled the sacred madrigal, the madrigale spirituale, which was a sacred variation on a popular secular form. Stylistically these motets are similar to his madrigals, and he published them throughout his career; occasionally they appeared in collections of madrigals, such as in his posthumous Fifth Book for five voices (1566), and he also included some in a collection of motets for five voices published in 1545.

- Passio Domini Nostri Jesu Christi Secundum Johannem: Judaei ergo quoniam parasceve erat

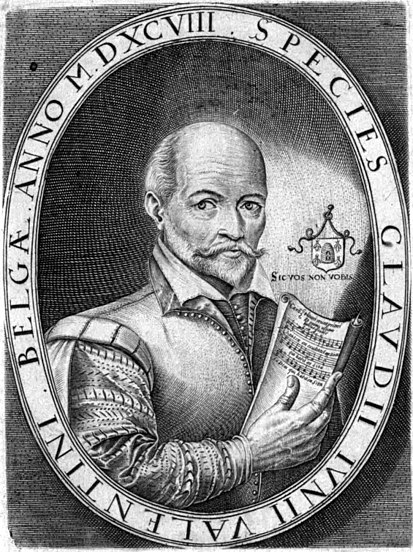

Adrian Le Roy (c.1520–1598) was an influential French music publisher, lutenist, mandore player, guitarist, composer and music educator. He achieved renown as a composer and arranger of songs and instrumentals, his published work including at least six books of tablature for the lute, five volumes for the guitar and arrangements for the cittern. Le Roy also helped to ensure the success of composer Orlande de Lassus, introducing him to court and publishing his music.

- Une m’avoit promis

- Mes pas semez

- Has tu point veu

- Passemeze

Thoinot Arbeau is the anagrammatic pen name of French cleric Jehan Tabourot (March 17, 1520 – July 23, 1595). Tabourot is most famous for his Orchésographie, a study of late sixteenth-century French Renaissance social dance. Orchésographie, first published in Langres, 1589, provides information on social ballroom behavior and on the interaction of musicians and dancers. It contains numerous woodcuts of dancers and musicians and includes many dance tabulations in which extensive instructions for the steps are lined up next to the musical notes, a significant innovation in dance notation at that time. The pavane “Belle qui tiens ma vie” was arranged by Leo Delibes for his incidental music for Victor Hugo’s play “Le roi s’amuse”. Other sections were arranged or quoted by Saint-Saens (in the “ballet” from Ascanio) and Peter Warlock (in his Capriol Suite). “Branle de l’Official” provided the tune for the 20th century English Christmas carol “Ding Dong Merrily on High”.

- Belle qui tiens ma vie

Philippe de Monte (1521 – 4 July 1603), sometimes known as Philippus de Monte, was a Flemish composer of the late Renaissance active all over Europe. He was a member of the 3rd generation madrigalists and wrote more madrigals than any other composer of the time. Sources cite him as being “the best composer in the entire country, particularly in the new manner and musica reservata.” Others compare his collections of music with that of other influential composers, such as Lassus.

Monte was a hugely prolific composer, and wrote both sacred and secular music primarily printed in the German language. He wrote about 40 masses and about 260 other sacred pieces, including motets and madrigali spirituali (works differing only from madrigals in that they have sacred texts). He published over 1100 secular madrigals, in 34 books, but not all of them survived. His first publication was in 1554 when he was 33.

Monte’s madrigals have been referred to as “the first and most mature fruits of the compositions for five voices.” Stylistically, Monte’s madrigals vary from an early, very progressive style with frequent use of chromaticism to express the text (though he was not quite as experimental in this regard as Marenzio or Lassus), to a late style which is much simplified, featuring short motifs and frequent homophonic textures. Some of his favorite poets of the time included Petrarch, Bembo, and Sannazaro. Unlike Monteverdi, who began in a conservative style and became experimental later in life, Monte’s compositional career had an opposite curve, progressing from experimentation to unity and simplicity in his later works. Some believe that this comes from his change in poetry selections, whereas others believe it was a reflection from the imperial courts.

Philippe de Monte was renowned all over Europe; editions of his music were printed, reprinted, and widely circulated. He had many students, including Gian Vincenzo Pinelli from Padua, thereby passing on his compositional skills and experience to the generation who developed the early Baroque style. Believed to be one of the most prominent composers, Philippe de Monte’s madrigals are still performed today.

- Missa si ambulavero: Sanctus & Agnus Die (à 6) (1587)

- Oimè, che belle lacrime fur quelle

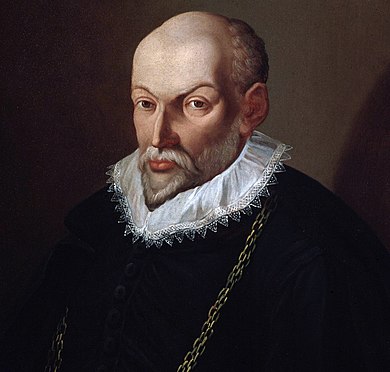

Giovanni Pierluigi da Palestrina (c. 1525 – 2 February 1594) was an Italian composer considered the central representative of the Roman School and the leading composer of late 16th-century Europe. Palestrina left hundreds of compositions, including 105 masses, 68 offertories, at least 140 madrigals and more than 300 motets. In addition, there are at least 72 hymns, 35 magnificats, 11 litanies, and four or five sets of lamentations. The Gloria melody from Palestrina’s Magnificat Tertii Toni (1591) is widely used today in the resurrection hymn tune, Victory (The Strife Is O’er).

His attitude toward madrigals was somewhat enigmatic: whereas in the preface to his collection of Canticum canticorum (Song of Songs) motets (1584) he renounced the setting of profane texts, only two years later he was back in print with Book II of his secular madrigals (some of these being among the finest compositions in the medium). He published just two collections of madrigals with profane texts, one in 1555 and another in 1586. The other two collections were spiritual madrigals, a genre beloved by the proponents of the Counter-Reformation.

Palestrina’s masses show how his compositional style developed over time. His Missa sine nomine seems to have been particularly attractive to Johann Sebastian Bach, who studied and performed it while writing the Mass in B minor. Most of Palestrina’s masses appeared in thirteen volumes printed between 1554 and 1601, the last seven published after his death.

One of the hallmarks of Palestrina’s music is that dissonances are typically relegated to the “weak” beats in a measure. This produced a smoother and more consonant type of polyphony which is now considered to be definitive of late Renaissance music, given Palestrina’s position as Europe’s leading composer (along with Orlande de Lassus and Victoria) in the wake of Josquin des Prez. The “Palestrina style” taught in college courses covering Renaissance counterpoint is often based on the codification by the 18th-century composer and theorist Johann Joseph Fux, published as Gradus ad Parnassum (Steps to Parnassus, 1725). Citing Palestrina as his model, Fux divided counterpoint into five (hence the term “species counterpoint”), designed as exercises for the student, which deployed progressively more elaborate rhythmic combinations of voices while adhering to strict harmonic and melodic requirements. The method was widely adopted and was the main basis of contrapuntal training in the 19th century, but Fux had introduced a number of simplifications to the Palestrina style, notably the obligatory use of a in whole notes, which were corrected by later authors such as Knud Jeppesen and R. O. Morris. Palestrina’s music conforms in many ways to Fux’s rules, particularly in the fifth species but does not fit his pedagogical format. The main insight, that the “pure” style of polyphony achieved by Palestrina followed an invariable set of stylistic and combinational requirements, was justified. Fux’s manual was endorsed by his contemporary J.S. Bach, who himself arranged two of Palestrina’s masses for performance.

According to Fux, Palestrina had established and followed these basic guidelines:

- The flow of music is dynamic, not rigid or static.

- Melody should contain few leaps between notes. (Jeppesen: “The line is the starting point of Palestrina’s style”.)

- If a leap occurs, it must be small and immediately countered by stepwise motion in the opposite direction.

- Dissonances are to be confined to suspensions, passing notes and weak beats. If one falls on a strong beat (in a suspension) it must be immediately resolved.

Fux omits to mention the manner in which the musical phrasing of Palestrina followed the syntax of the sentences he was setting to music, something not always observed by earlier composers. Also to be noticed in Palestrina is a great deal of tone painting. Elementary examples of this are descending musical motion with Latin words like descendit (descends) or of a static musical or cadential moment with the words de coelis (from heaven).

Palestrina was extremely famous in his day, and if anything, his reputation and influence increased after his death. Felix Mendelssohn placed him in the pantheon of the greatest musicians, writing, “I always get upset when some praise only Beethoven, others only Palestrina and still others only Mozart or Bach. All four of them, I say, or none at all.”. Conservative music of the Roman school continued to be written in Palestrina’s style (which in the 17th century came to be known as the prima pratica) by such students of his as Giovanni Maria Nanino, Ruggiero Giovanelli, Arcangelo Crivelli, Teofilo Gargari, Francesco Soriano, and Gregorio Allegri. As late as the 1750s, Palestrina’s style was still the reference for composers working in the motet form, as can be seen by Francesco Barsanti’s Sei Antifones ‘in the style of Palestrina’ (c. 1750; published by [Peter] Welcker, c. 1762). Much research on Palestrina was done in the 19th century by Giuseppe Baini, who published a monograph in 1828 which made Palestrina famous again and reinforced the already existing legend that he was the “Savior of Church Music” during the reforms of the Council of Trent. 20th and 21st century scholarship by and large retains the view that Palestrina was a strong and refined composer whose music represents a summit of technical perfection. Contemporary analysis highlighted the modern qualities in the compositions of Palestrina such as use of color and sonority, use of sonic grouping in large-scale setting, interest in vertical as well as horizontal organization, studied attention to text setting. These unique characteristics, together with effortless delivery and an indefinable “otherness”, constitute to this day the attraction of Palestrina’s work.

- Motettorum – Liber Secundus: No. 16 Peccantem me quotidie (1572)

- Motettorum – Liber Quintus: VI. Parce mihi, Domine (1584)

- Tribulations civitatum audivimus (1584)

- Alma Redemptoris Mater, Tu quae genuisti (Motet for 4 voices) [1587]

- Magnificat quarti toni (1591)

Francisco Guerrero (October 4 (?), 1528 – November 8, 1599) was a Spanish Catholic priest and composer. Of all the Spanish Renaissance composers, he lived and worked the most in Spain. Others—for example Morales and Victoria—spent large portions of their careers in Italy (though, unlike many Franco-Flemish composers of the time, Spanish composers usually returned home later in life). Guerrero’s music was both sacred and secular, unlike that of Victoria and Morales, the two other Spanish 16th-century composers of the first rank. He wrote numerous secular songs and instrumental pieces, in addition to masses, motets, and Passions. He was able to capture an astonishing variety of moods in his music, from ecstasy to despair, longing, joy, and devotional stillness; his music remained popular for hundreds of years, especially in cathedrals in Latin America. Stylistically he preferred homophonic textures, rather like his Spanish contemporaries, and he wrote memorable, singable lines. One interesting feature of his style is how he anticipated functional harmonic usage: there is a case of a Magnificat discovered in Lima, Peru, once thought to be an anonymous 18th century work, which turned out to be a work of his.

- Si Tus Penas No Pruevo

- O Domine Jesu Christe

- Ave virgo sanctissima

Claude Le Jeune (1528 to 1530 – buried 26 September 1600) was a Franco-Flemish composer who was the primary representative of the musical movement known as musique mesurée, and a significant composer of the “Parisian” chanson, the predominant secular form in France in the latter half of the 16th century. His fame was widespread in Europe, and he ranks as one of the most influential composers of the time.

Le Jeune was the most famous composer of secular music in France in the late 16th century, and his preferred form was the chanson. After 1570, most of the chansons he wrote incorporated the ideas of musique mesurée, the musical analogue to the poetic movement known as vers mesurée, in which the music reflected the exact stress accents of the French language. In musique mesurée, stressed versus unstressed syllables in the text would be set in a musical ratio of 2:1, i.e. a stressed syllable could get a quarter note while an unstressed syllable could get an eighth note. Since the meter of the verse was usually flexible, the result was a musical style which is best transcribed without meter, and which sounds to the modern ear to have rapidly changing meters, for example alternating 2/8, 3/8, etc.

In opposition to the chanson style of the Netherlandish composers writing at the same time, Le Jeune’s “Parisian” chansons in musique mesurée were usually light and homophonic in texture. They were sung a cappella, and were usually from three to seven voices, though sometimes he wrote for as many as eight. Probably his most famous secular work is his collection of thirty-three airs mesurés and six chansons, all to poems by Baïf, entitled Le printemps. Occasionally he wrote in a contrapuntal idiom reminiscent of the more severe style of his Netherlandish contemporaries, sometimes with a satirical intent; and in addition he sometimes used melodic intervals which were “forbidden” by current rules, such as the expressive diminished fourth; these strictures were codified by contemporary theorists such as Gioseffe Zarlino in Venice, and were well known to Le Jeune.

Le Jeune also was keenly aware of the current humanist research into ancient Greek music theory. Greek use of the modes and the three genera intrigued him, and in his music he used both the diatonic genus (a tetrachord made up of semitone, tone, and tone) and the chromatic genus (a tetrachord made up of semitone, semitone, and an augmented second). (The enharmonic genus, consisting of quarter tone, quarter tone, and major third, was rarely used in the 16th century, although Italian theorist and composer Nicola Vicentino constructed an instrument allowing it to be used in performance.) His chansons using the chromatic genus are among the most chromatic compositions prior to the madrigals of Gesualdo.

Probably Le Jeune’s most famous sacred work is his Dodécacorde, a series of twelve psalm settings which he published in La Rochelle in 1598. Each of the psalms is set in a different one of the twelve modes as given by Zarlino. Some of his psalm settings are for large forces: for example he uses sixteen voices in his setting of Psalm 52. Published posthumously was a collection of all 150 psalms, Les 150 pseaumes, for four and five voices; some of these were extremely popular, and were reprinted in several European countries throughout the 17th century.

His last completed work, published in 1606, was a collection of thirty-six songs based on eight-line poems, divided into twelve groups, each of which contained three settings in each of the twelve modes. The work, Octonaires de la vanité et inconstances du monde (Eight-line Poems on the Vanity and Inconstancy of the World), based on poems by the Calvinist preacher Antoine de Chandieu, was for groups of three or four voices. According to Le Jeune’s sister Cecile, who wrote the introduction to the publication, he had intended to complete another set for more voices but died before finishing it. It was one of the last collections of chansons of the Renaissance, of any type; following its publication, the air de cour was the predominant genre of secular song composition in France.

Of Le Jeune’s sacred music, a total of 347 psalm settings, thirty-eight sacred chansons, eleven motets, and a mass setting have survived. His secular output included 146 airs, most of which were in the style of musique mesurée, as well as sixty-six chansons, and forty-three Italian madrigals. In addition, three instrumental fantasias were published posthumously in 1612, as well as some works for lute. He was fortunate in that his copious manuscripts were published after his death: his friend, the equally gifted and prolific composer Jacques Mauduit, was fated to have most of his music lost.

Contemporary critics accused Le Jeune of violating some of the rules of good melodic writing and counterpoint, for example using the melodic interval of the major sixth (something Palestrina would never have done), and frequently crossing voices; some of these compositional devices were to become features of the Baroque style, premonitions of which were beginning to appear even in France towards the end of the 16th century.

- Povre coeur entourné

Orlando di Lasso (Orlande de Lassus; probably c. 1532 – 14 June 1594) was chief representative of the mature polyphonic style in the Franco-Flemish school, Lassus stands with William Byrd, Giovanni Pierluigi da Palestrina, and Tomás Luis de Victoria as the leading composers of the later Renaissance. One of the most prolific, versatile, and universal composers of the late Renaissance, Lasso wrote over 2,000 works in all Latin, French, Italian and German vocal genres known in his time. These include 530 motets, 175 Italian madrigals and villanellas, 150 French chansons, and 90 German lieder. No strictly instrumental music by Lasso is known to survive, or ever to have existed: an interesting omission for a composer otherwise so wide-ranging and prolific, during an age when instrumental music was becoming an ever-more prominent means of expression, all over Europe.

Lasso remained Catholic during this age of religious discord, though this neither hindered him in writing worldly secular songs nor in employing music originally to racy texts in his Magnificats and masses employing parody technique. Nevertheless, the Catholic Counter-Reformation, which under Jesuit influence was reaching a peak in Bavaria in the late sixteenth century, had a demonstrable impact on Lasso’s late work, including the liturgical music for the Roman Rite, the burgeoning number of Magnificats, the settings of the Catholic Ulenberg Psalter (1588), and especially the great penitential cycle of spiritual madrigals, the Lagrime di San Pietro (1594).

Almost 60 masses have survived complete; most of them are parody masses) using as melodic source material secular works written by himself or other composers. Technically impressive, they are nevertheless the most conservative part of his output. He usually conformed the style of the mass to the style of the source material, which ranged from Gregorian chant to contemporary madrigals, but always maintained an expressive and reverent character in the final product.

Several of his masses are based on extremely secular French chansons; some of the source materials were outright obscene. Entre vous filles de quinze ans, “Oh you fifteen-year old girls”, by Jacob Clemens non Papa, gave him source material for his 1581 Missa entre vous filles, probably the most scandalous of the lot. This practice was not only accepted but encouraged by his employer, which can be confirmed by evidence from their correspondence, much of which has survived.

In addition to his traditional imitation masses, he wrote a considerable quantity of missae breves, “brief masses”, syllabic short masses meant for brief services (for example, on days when Duke Albrecht went hunting: evidently he did not want to be detained by long-winded polyphonic music). The most extreme of these is a work actually known as the Jäger Mass (Missa venatorum)—the “Hunter’s Mass”.

Some of his masses show influence from the Venetian School, particularly in their use of polychoral techniques (for example, in the eight-voice Missa osculetur me, based on his own motet). Three of his masses are for double choir, and they may have been influential on the Venetians themselves; after all, Andrea Gabrieli visited Lasso in Munich in 1562, and many of Lasso’s works were published in Venice. Even though Lasso used the contemporary, sonorous Venetian style, his harmonic language remained conservative in these works: he adapted the texture of the Venetians to his own artistic ends.

Lasso is one of the composers of a style known as musica reservata—a term which has survived in many contemporary references, many of them seemingly contradictory. The exact meaning of the term is a matter of fierce debate, though a rough consensus among musicologists is that it involves intensely expressive setting of text and chromaticism, and that it may have referred to music specifically written for connoisseurs. A famous composition by Lasso representative of this style is his series of 12 motets entitled Prophetiae Sibyllarum, in a wildly chromatic idiom which anticipates the work of Gesualdo; some of the chord progressions in this piece were not to be heard again until the 20th century.

Lasso wrote four settings of the Passion, one for each of the Evangelists, St. Matthew, Mark, Luke and John. All are for a cappella voices. He sets the words of Christ and the narration of the Evangelist as chant, while setting the passages for groups polyphonically.

As a composer of motets, Lasso was one of the most diverse and prodigious of the entire Renaissance. His output varies from the sublime to the ridiculous, and he showed a sense of humor not often associated with sacred music: for example, one of his motets satirizes poor singers (his setting of Super flumina Babylonis, for five voices) which includes stuttering, stopping and starting, and general confusion; it is related in concept if not in style to Mozart’s A Musical Joke. Many of his motets were composed for ceremonial occasions, as could be expected of a court composer who was required to provide music for visits of dignitaries, weddings, treaties and other events of state. But it was as a composer of religious motets that Lasso achieved his widest and most lasting fame.

Lasso’s 1584 setting of the seven Penitential Psalms of David (Psalmi Davidis poenitentiales), ordered by King Charles IX of France, is one of the most famous collections of psalm settings of the entire Renaissance. According to George T. Ferris, it was claimed by some that he ordered them as an expiation of his soul after the massacre of St. Bartholomew of the Huguenots. The counterpoint is free, avoiding the pervasive imitation of the Netherlanders such as Gombert, and occasionally using expressive devices foreign to Palestrina. As elsewhere, Lasso strives for emotional impact, and uses a variety of texture and care in text-setting towards that end. The penultimate piece in the collection, his setting of the De profundis (Psalm 129/130), is considered by many scholars to be one of the high-water marks of Renaissance polyphony, ranking alongside the two settings of the same text by Josquin des Prez. Among his other liturgical compositions are hymns, canticles (including over 100 Magnificats), responsories for Holy Week, Passions, Lamentations, and some independent pieces for major feasts.

Lasso wrote in all the prominent secular forms of the time. In the preface to his collection of German songs, Lasso lists his secular works: Italian madrigals and French chansons, German and Dutch songs. He is probably the only Renaissance composer to write prolifically in five languages – Latin in addition to those mentioned above – and he wrote with equal fluency in each. Many of his songs became hugely popular, circulating widely in Europe. In these various secular songs, he conforms to the manner of the country of origin while still showing his characteristic originality, wit, and terseness of statement.

In his madrigals, many of which he wrote during his stay in Rome, his style is clear and concise, and he wrote tunes which were easily memorable; he also “signed” his work by frequently using the word ‘lasso’ (and often setting with the solfège syllables la-sol, i.e. A-G in the key of C). His choice of poetry varied widely, from Petrarch for his more serious work to the lightest verse for some of his amusing canzonettas. Lasso often preferred cyclic madrigals, i.e. settings of multiple poems in a group as a set of related pieces of music. For example, his fourth book of madrigals for five voices begins with a complete sestina by Petrarch, continues with two-part sonnets, and concludes with another sestina: therefore the entire book can be heard as a unified composition with each madrigal a subsidiary part.

Another form which Lasso cultivated was the French chanson, of which he wrote about 150. Most of them date from the 1550s, but he continued to write them even when he was in Germany: his last productions in this genre come from the 1580s. They were enormously popular in Europe, and of all his works, they were the most widely arranged for instruments such as lute and keyboard. Most were collected in the 1570s and 1580s in three publications: one by Petrus Phalesius the Elder in 1571, and two by Le Roy and Ballard in 1576 and 1584. Stylistically, they ranged from the dignified and serious, to playful, bawdy, and amorous compositions, as well as drinking songs suited to taverns. Lasso followed the polished, lyrical style of Sermisy rather than the programmatic style of Clément Janequin for his writing. One of the most famous of Lasso’s drinking songs was used by Shakespeare in Henry IV, Part II. English words are fitted to Un jour vis un foulon qui fouloit (as Monsieur Mingo) and sung by the drunken Justice Silence, in Act V, Scene iii.

A third type of secular composition by Lasso was the German Lied. Most of these he evidently intended for a different audience, since they are considerably different in tone and style from either the chansons or madrigals; in addition, he wrote them later in life, with none appearing until 1567, when he was already well-established at Munich. Many are on religious subjects, although light and comic verse is represented as well. He also wrote drinking songs in German, and contrasting with his parallel work in the genre of the chanson, he also wrote songs on the unfortunate aspects of overindulgence.

- Timor et tremor

- Exaudi, Deus. orationem meam

- Prophetiae Sibyllarum: Prologue

- Prophetiae Sibyllarum: No. 1, Sibylla Persica “Virgine matre”

- Prophetiae Sibyllarum: No. 2, Sibylla Lybica “Ecce dies venient”

- Prophetiae Sibyllarum: No. 3, Sibylla Delphica “Non tarde”

- Prophetiae Sibyllarum: No. 4, Sibylla Cimmeria “In teneris”

- Prophetiae Sibyllarum: No. 5, Sibylla Samia “Ecce dies nigras”

- Prophetiae Sibyllarum: No. 6, Sibylla Cumana “Jam mea”

- Prophetiae Sibyllarum: No. 7, Sibylla Hellespontica “Dum meditor”

- Prophetiae Sibyllarum: No. 8, Sibylla Phrygia “Ipsa Deum”

- Prophetiae Sibyllarum: No. 9, Sibylla Europaea “Virginis aeternum”

- Prophetiae Sibyllarum: No. 10, Sibylla Tiburtina “Verax ipse”

- Prophetiae Sibyllarum: No. 11, Sibylla Erythaea “Cerno Dei”

- Prophetiae Sibyllarum: No. 12, Sibylla Agrippa “Summus erit”

Andrea Gabrieli (1532/1533 – August 30, 1585) was an Italian composer and organist. The uncle of the somewhat more famous Giovanni Gabrieli, he was the first internationally renowned member of the Venetian School of composers, and was extremely influential in spreading the Venetian style in Italy as well as in Germany. Gabrieli was a prolific and versatile composer, and wrote a large amount of music, including sacred and secular vocal music, music for mixed groups of voices and instruments, and purely instrumental music, much of it for the huge, resonant space of St. Mark’s. His works include over a hundred motets and madrigals, as well as a smaller number of instrumental works.

His early style is indebted to Cipriano de Rore, and his madrigals are representative of mid-century trends. Even in his earliest music, however, he had a liking for homophonic textures at climaxes, foreshadowing the grand style of his later years. After his meeting with Lassus in 1562, his style changed considerably, and the Netherlander became the strongest influence on him. Once Gabrieli was working at St. Mark’s, he began to turn away from the Franco-Flemish contrapuntal style which had dominated the music of the 16th century, instead exploiting the sonorous grandeur of mixed instrumental and vocal groups playing antiphonally in the great basilica. His music of this time uses repetition of phrases with different combinations of voices at different pitch levels; although instrumentation is not specifically indicated, it can be inferred; he carefully contrasts texture and sonority to shape sections of music in a way which was unique, and which defined the Venetian style for the next generation. Not everything Gabrieli wrote was for St. Mark’s, though. He provided the music for one of the earliest revivals of an ancient Greek drama in Italian translation: Oedipus tyrannus, by Sophocles, for which he wrote the music for the choruses, setting separate lines for different groupings of voices. It was produced at the inauguration of the Teatro Olimpico, Vicenza, 1585. Evidently Andrea Gabrieli was reluctant to publish much of his own music, and his nephew Giovanni Gabrieli published much of it after his uncle’s death.

- In ecclesiis a 14

- Benedictus es Dominus a 8

Jehan Chardavoine (baptized on 2 February 1538 – died c. 1580) was a French composer mostly active in Paris. He was one of the first known editors of popular chansons, and the author, according to musicologist Julien Tiersot, of “the only volume of monodic songs from the 16th century that has survived to our days.”

Jehan Chardavoine is mostly known for his publication, Recueil des plus belles et excellentes chansons en forme de voix de ville, tirées de divers autheurs et Poëtes François, tant anciens que modernes. Ausquelles a esté nouvellement adaptée la Musique de leur chant commun, à fin que chacun les puisse chanter en tout endroit qu’il se trouvera, tant de voix que sur les instruments (“Collection of the most beautiful and excellent songs in the form of voix de ville, taken from various French authors and poets, both ancient and modern. To which texts have been newly adapted the music of their main tune, so that anyone may sing it at whichever place they may be, on voice as well as on instruments.”). Published in 1576, it is the oldest collection of French popular songs ever printed. It contains 186 songs based on strophic poems. Some of the songs were simply collected and published by Chardavoine, while others are his own adaptation to monody of previous polyphonic works by composers such as Jacques Arcadelt, Pierre Certon, and Pierre Cléreau. In most cases, he has transformed the original music to such an extent that it can be considered a new work.

Some of the poems to which Chardavoine adapted new music were anonymous, while others were by poets of his time, such as Clément Marot, Mellin de Saint-Gelais, Jean-Antoine de Baïf, Pierre de Ronsard and Joachim du Bellay. Among the poems set to music and published in his anthology are the famous Mignonne allons voir si la rose and Ma petite colombelle, by Ronsard; Si vous regardez madame, by Du Bellay; and Longtemps y a que je vis en espoir, by Marot. Some of these airs have been reused by the polyphonists.

- Mignonne allons voir si la rose

William Byrd ( c. 1540 – 4 July 1623) was an English composer considered among the greatest composers of the Renaissance, he had a profound influence on composers both from his native country and on the Continent. He is often considered along with John Dunstaple, Thomas Tallis and Henry Purcell as one of England’s most important composers of early music. Byrd wrote in many of the forms current in England at the time, including various types of sacred and secular polyphony, keyboard (the so-called Virginalist school), and consort music. He produced sacred music for Anglican services, but during the 1570s became a Roman Catholic, and wrote Catholic sacred music later in his life.

Byrd’s output of about 470 compositions amply justifies his reputation as one of the great masters of European Renaissance music. Perhaps his most impressive achievement as a composer was his ability to transform so many of the main musical forms of his day and stamp them with his own identity. Having grown up in an age in which Latin polyphony was largely confined to liturgical items for the Sarum rite, he assimilated and mastered the Continental motet form of his day, employing a highly personal synthesis of English and continental models. He virtually created the Tudor consort and keyboard fantasia, having only the most primitive models to follow. He also raised the consort song, the church anthem and the Anglican service setting to new heights. Finally, despite a general aversion to the madrigal, he succeeded in cultivating secular vocal music in an impressive variety of forms in his three sets of 1588, 1589 and 1611.

- Ave verum corpus, T. 92

- The Bells MB38

- Fantasia III

- Come Woeful Orpheus

- Ah Silly Soul

- In nomine II

Gioseppe Caimo (c. 1545 – 1584) was an Italian composer and organist mainly active in Milan. He was a prolific composer of madrigals and other secular vocal music, and was one of the most prominent musicians in Milan in the 1570s and early 1580s. His style represents the shift from the popular villanella for three voices to the later canzonetta which was much like a madrigal. His early music shows the influence of the French chanson, as well as the native tradition of popular song. Musically, his canzonettas are light, graceful, and unpretentious. Other music of his is more adventurous, such as three chromatic madrigals in terza rima, referred to by musicologist Iain Fenlon as “gloomy … [and] entirely appropriate texts for a city suffering from exorbitant taxation, economic depression and violence caused by Spanish oppression. “Caimo’s chromaticism is most extreme in his fourth book of madrigals, which was for five voices and published the year of his death (1584). He includes passages with chromatic mediants – chords with roots a third apart – as well as circle-of-fifths passages that reach harmonically remote regions, such as G-flat, something done rarely even during this experimental time, the decades prior to the development of functional tonality.

- Piangete valli

Tomás Luis de Victoria c. 1548 – c. 20–27 August 1611) was the most famous Spanish composer of the Renaissance. He stands with Giovanni Pierluigi da Palestrina and Orlande de Lassus as among the principal composers of the late Renaissance, and was “admired above all for the intensity of some of his motets and of his Offices for the Dead and for Holy Week”. His surviving oeuvre, unlike that of his colleagues, is almost exclusively sacred and polyphonic vocal music, set to Latin texts. As a Catholic priest, as well as an accomplished organist and singer, his career spanned both Spain and Italy. However, he preferred the life of a composer to that of a performer.

Victoria was a master at overlapping and dividing choirs with multiple parts with a gradual decreasing of rhythmic distance throughout. Not only does Victoria incorporate intricate parts for the voices, but the organ is almost treated like a soloist in many of his choral pieces. Victoria did not originate the development of psalm settings or antiphons for two choirs, but he continued and increased the popularity of such repertoire.

Stylistically, his music shuns the elaborate counterpoint of many of his contemporaries, preferring simple line and homophonic textures, yet seeking rhythmic variety and sometimes including intense and surprising contrasts. His melodic writing and use of dissonance is more free than that of Palestrina; occasionally he uses intervals which are prohibited in the strict application of 16th century counterpoint, such as ascending major sixths, or even occasional diminished fourths. Victoria sometimes uses dramatic word-painting, of a kind usually found only in madrigals. Some of his sacred music uses instruments (a practice which is not uncommon in Spanish sacred music of the 16th century), and he also wrote polychoral works for more than one spatially separated group of singers, in the style of the composers of the Venetian school who were working at St. Mark’s in Venice.

- Incipit Oratio Jeremiae Propetae

- Liturgia de Pascua en el Madrid de los Austrias/Missa Laetatus sum: Kyrie [Ad Missam]

- Liturgia de Pascua en el Madrid de los Austrias/Missa Laetatus sum: Gloria [Ad Missam]

- Liturgia de Pascua en el Madrid de los Austrias/Missa Laetatus sum: Sanctus [Ad Missam]

- Ave Maria a 4: I. Ave Maria, gratia plena

- Ave Maria a 4: II. Sancta Maria, mater Dei

Giovanni de Macque (1548/1550 – September 1614) was a Netherlandish composer who spent almost his entire life in Italy. He was one of the most famous Neapolitan composers of the late 16th century; some of his experimentation with chromaticism was likely influenced by Carlo Gesualdo, who was an associate of his.

Macque was a prolific madrigalist, who published 12 separate books of madrigals. After 1585, when he moved to Naples, his music shifted from the conservative Roman style to the more progressive Neapolitan one. His early and late madrigals include both light and serious music and often require virtuoso singing skill.

After 1599, his music shifted in style again; Macque began experimenting with chromaticism of the kind found in Gesualdo’s madrigals. Most likely the nobleman influenced Macque, but it is possible that some of the influence went the other way, since the dating of Gesualdo’s individual compositions is difficult, due to his publication of his work in large blocks, many years apart. Some of the madrigals Macque wrote after 1599 include “forbidden” melodic intervals (such as sevenths), chords entirely outside of the Renaissance modal universe (such as F# major) and melodic passages in consecutive chromatic semitones.

In addition to his madrigals, he was a prolific composer of instrumental music, writing canzonas, ricercars, capriccios and numerous pieces for organ. Macque also wrote sacred music, including a book of motets for five to eight voices, litanies, laudi spirituali, and contrafactum motets (motets originally in another language, fitted with new texts known as contrafacta).

- Io piango o Filli

Jacobus Gallus (between 15 April and 31 July 1550 – 18 July 1591) was a composer of presumed Slovene ethnicity. Born in Carniola, which at the time was one of the Habsburg lands in the Holy Roman Empire, he lived and worked in Moravia and Bohemia during the last decade of his life.

Gallus represented the Counter-Reformation in Bohemia, mixing the polyphonic style of the High Renaissance Franco-Flemish School with the style of the Venetian School. His output was both sacred and secular, and hugely prolific: over 500 works have been attributed to him. Some are for large forces, with multiple choirs of up to 24 independent parts.

His most notable work is the six-part Opus musicum, 1587, a collection of 374 motets that would eventually cover the liturgical needs of the entire ecclesiastical year. His wide-ranging, eclectic style blended archaism and modernity. He rarely used the cantus firmus technique, preferring the then-new Venetian polychoral manner, yet he was equally conversant with earlier imitative techniques. Some of his chromatic transitions foreshadowed the breakup of modality; his five-voice motet Mirabile mysterium contains chromaticism worthy of Carlo Gesualdo. He enjoyed word painting in the style of the madrigal, yet he could write the simple Ecce quomodo moritur justus later used by George Frideric Handel in his funeral anthem The Ways of Zion Do Mourn.

His secular output, about 100 short pieces, was published in the collections Harmoniae morales (Prague 1589 and 1590) and Moralia (Nuremberg 1596). Some of these works were madrigals in Latin, an unusual language for the form (most madrigals were in Italian); others were songs in German, and others were compositions in Latin.

- Miracle mysterium

- Ecce quomodo mortiur iustus

- Lamentations Jeremiae Prophetae: Miserere mei Deus

Alonso Lobo (February 25, 1555 (baptised) – April 5, 1617) was a Spanish composer of the late Renaissance. Although not as famous as Tomás Luis de Victoria, he was highly regarded at the time, and Victoria himself considered him to be his equal.

Lobo’s music combines the smooth contrapuntal technique of Palestrina with the sombre intensity of Victoria. Some of his music also uses polychoral techniques, which were common in Italy around 1600, though Lobo never used more than two choirs. Lobo was influential far beyond the borders of his native Spain: in Portugal, and as far away as Mexico, for the next hundred years or more he was considered to be one of the finest Spanish composers.

His works include masses and motets, three Passion settings, Lamentations, psalms and hymns, as well as a Miserere for 12 voices (which has since become lost). His best-known work, Versa est in luctum, was written on the death of Philip II in 1598. No secular or instrumental music by Lobo is known to survive today.

- Versa est in luctum

- O quam suavis est, Domine

Pierre-Francisque Caroubel (1556 – summer 1611 or 1615) was a French violinist and composer. He is known for his dance music, bransles (he composed “Le Branle De Montirande”) and galliards.

- Gaillarde à 5 (I)

- Passameze à 5

- Bransles simples 1 & 2 à 5

Giovanni Croce (1557 – 15 May 1609) was an Italian composer of the late Renaissance, of the Venetian School. He was particularly prominent as a madrigalist, one of the few among the Venetians other than Monteverdi and Andrea Gabrieli.

Croce wrote less music in the grand polychoral style than Andrea and Giovanni Gabrieli, although he left a grand mass for four choirs, composed for Ferdinand of Austria (the future Emperor Ferdinand II) and several triple-choir Psalm settings (only one of which has survived), and as a result his music has not maintained the same fame to the present day; however he was renowned as a composer at the time, and had a large influence on music both in Italy and abroad. As a composer of sacred music he was mostly conservative, writing cori spezzati in the manner of Adrian Willaert, and parody masses more like the music composed by the members of the contemporary Roman School. However, later in his career he wrote some music in a forward-looking concertato style, which attempted to combine the innovations of Viadana with the grand Venetian polychoral manner. This posthumous collection, the Sacre Cantilene Concertate of 1610, is for 3, 5 or 6 solo voices, continuo and a 4-voice Ripieno which can be multiplied ad lib (presumably in different parts of the church). Most of Croce’s sacred music is for double-choir: this includes three masses, two books of motets, and sets of music for Terce, Lauds and Vespers. Although most of his sacred music was written for the professional singers of St Mark’s (including several pieces written for their participation in a freelance company of musicians under Croce’s direction, who performed for the Scuole Grande of Venice) much of his music is technically simple: for that reason much of it, especially the secular music, has remained popular with amateurs. One collection, the motets for 4 voices of 1597, is clearly designed for less ambitious church choirs.

Croce is also credited with the first published continuo parts, many of his double-choir collections being issued either with a ‘Basso per sonare nell’organo’ or a ‘Partidura’ (or Spartidura) which indicated both choirs.

Stylistically, Croce was more influenced by Andrea Gabrieli than his nephew Giovanni, even though they were exact contemporaries; Croce preferred the emotional coolness, the Palestrinian clarity and the generally lighter character of Andrea’s music. Croce was particularly important in the development of the canzonetta and the madrigal comedy, and wrote a large quantity of easily singable, popular, and often hilarious music. Some of his collections are satirical, for example setting to music ridiculous scenes at Venetian carnivals (Mascarate piacevoli et ridicolose per il carnevale, 1590), some of which are in dialect.

Croce was one of the first composers to use the term capriccio, as a title for one of the canzonettas in his collection Triaca musicale (musical cure for animal bites) of 1595. Both this and the Mascarate piacevoli collections were intended to be sung in costumes and masks at Venetian carnivals.

His canzonettas and madrigals were influential in the Netherlands and in England, where they were reprinted in the second book of Musica transalpina (1597), one of the collections which inaugurated the mania for madrigal composition there. Croce’s music remained popular in England and Thomas Morley specifically singled him out as a master composer; indeed Croce may have been the biggest single influence on Morley. John Dowland visited him in Italy as well.

- In spiritu humilitatis

Thomas Morley (1557 – early October 1602) was an English composer, theorist, singer and organist of the late Renaissance. He was one of the foremost members of the English Madrigal School. Referring to the strong Italian influence on the English madrigal, The New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians states that Morley was “chiefly responsible for grafting the Italian shoot on to the native stock and initiating the curiously brief but brilliant flowering of the madrigal that constitutes one of the most colorful episodes in the history of English music.”

While Morley attempted to imitate the spirit of Byrd in some of his early sacred works, it was in the form of the madrigal that he made his principal contribution to music history. His work in the genre has remained in the repertory to the present day, and shows a wider variety of emotional color, form and technique than anything by other composers of the period. Usually his madrigals are light, quick-moving and easily singable, like his well-known “Now Is the Month of Maying” (which is actually a ballett); he took the aspects of Italian style that suited his personality and anglicised them. Other composers of the English Madrigal School, for instance Thomas Weelkes and John Wilbye, were to write madrigals in a more serious or sombre vein.

In addition to his madrigals, Morley wrote instrumental music, including keyboard music (some of which has been preserved in the Fitzwilliam Virginal Book), and music for the broken consort, a uniquely English ensemble of two viols, flute, lute, cittern and bandora.

Morley’s Plaine and Easie Introduction to Practicall Musicke (published 1597) remained popular for almost two hundred years after its author’s death, and is still an important reference for information about sixteenth century composition and performance.

- How Long Wilt Thou Forget Me?

- Madrigals: No. 3, Now Is the Month of Maying

- Fantasia

Jean Planson or Jehan Planson (c. 1559 – c. 1611) was a French composer and organist. Planson’s secular compositions were influenced by composers from L’Académie de musique et de poésie, such as Joachim Thibault de Courville, Fabrice Marin Caietain and Claude Le Jeune. They are syllabic and homophonic, with the melody above, and short phrases. The texts on which he composes are mainly inspired by the pastoral movement, illustrated by Rémy Belleau, Siméon-Guillaume de La Roque and Jean Bertaut. Most of them were later published in a poetic collection without music in 1597, reissued several times.

- Ma bergere, ma lumiere

- Une nimphe jolie

Hieronymus Praetorius (10 August 1560 – 27 January 1629) was a Northern German composer and organist of the late Renaissance and early Baroque whose polychoral motets in 8 to 20 voices are intricate and vividly expressive.